Over the past few months, battles between the Myanmar military and the Arakan Army (AA) have increased in Rakhine and Chin states. Initially during the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) administration, and now during the National League for Democracy (NLD) administration, ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) that once had limited numbers and military capabilities have gained in strength by allying with more powerful EAOs, posing a challenge to the peace process. The continued insistence by the government and military that all EAOs sign the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) before engaging in further substantive dialogue has only exacerbated the many armed conflicts in the country.

Along with ongoing fighting in Kachin and northern Shan state, the clashes in Rakhine and Chin states come as the peace process is faltering even among groups who are already signatories to the NCA. The Karen National Union/Karen National Liberation Army (KNU/KNLA) and the Restoration Council of Shan State/Shan State Army-South (RCSS/SSA-S), two key signatories to the NCA, have suspended their participation in formal peace negotiations (The Irrawaddy, 12 November 2018). While informal meetings have since been held in an attempt bring these groups back into the formal process, the military continues to hold to its six-point plan while EAOs argue for more attention to issues of equality and self-determination in the building of a democratic federal union. EAOs have also pushed for the inclusion of all ethnic armed groups in the formal peace talks, not just those who have signed the NCA (The Irrawaddy, 19 November 2018).

The Myanmar government and military have long refused to include the Arakan Army (AA), as well as the Palaung State Liberation Front/Ta’ang National Liberation Army (PSLF/TNLA) and Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), in formal peace talks now held under the banner of the 21st Century Union Peace Conference. It is the lack of inclusion in the formal peace process that led these three groups to band with four other non-signatory EAOs to form the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee (FPNCC) in an attempt to gain leverage in arguing for a new framework for peace negotiations. When the government’s Peace Commission met informally with the AA, PSLF/TNLA, and MNDAA in Kunming, China concerning the possibility of joining the 21st Century Panglong Union Peace Conference, the three groups expressed a willingness to find a political solution to the ongoing armed conflicts, though details on a way forward have not yet been forthcoming (The Irrawaddy, 13 December 2018).

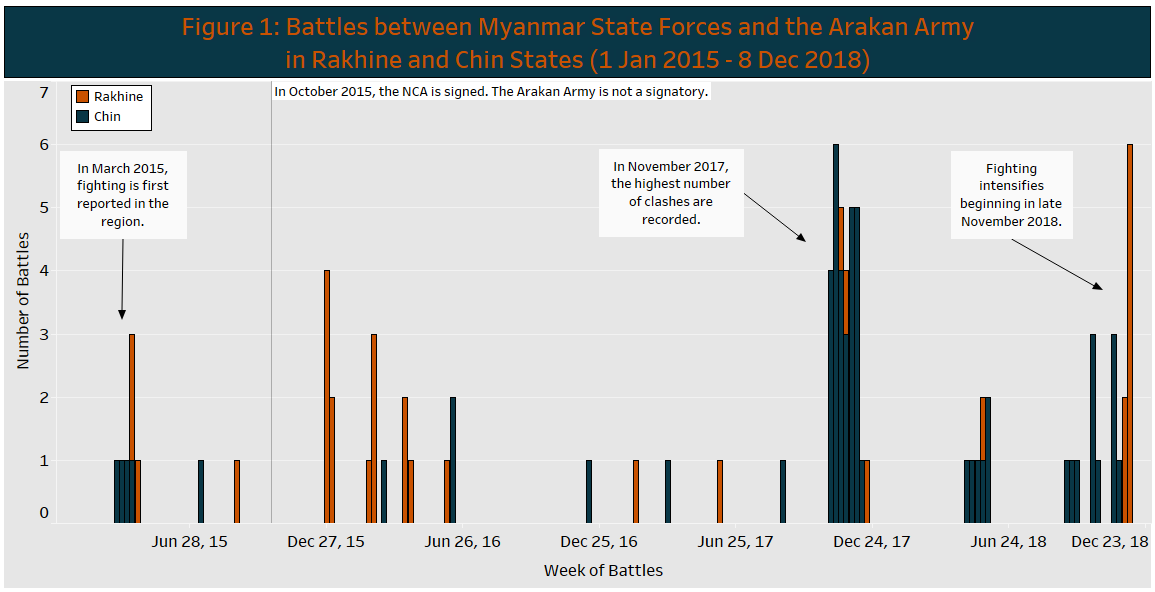

It is against this backdrop that conflict in Rakhine and Chin states has been on the rise (see Figure 1). Drawing recruits partly from Rakhine working in the mines in Hpakant, Kachin state (Asia Times, 11 June 2017), the AA is believed to be around 3,000 strong (Myanmar Peace Monitor, 12 December 2018). Having been trained and supported by the Kachin Independence Organization/Kachin Independence Army (KIO/KIA), the AA has gained battlefield experience fighting alongside the KIO/KIA in Kachin and northern Shan state. They have likewise fought in joint operations with the PSLF/TNLA and MNDAA, groups that the KIO/KIA also trained and supported. The four groups have fought together in various combinations, often under the name the Northern Alliance. In 2015, coming off fighting alongside the MNDAA in their battles with the Myanmar military in the Kokang area of Shan state, the AA began engaging in clashes with the Myanmar military in Rakhine and Chin states. The heaviest fighting between the AA and the Myanmar military occurred in November 2017.

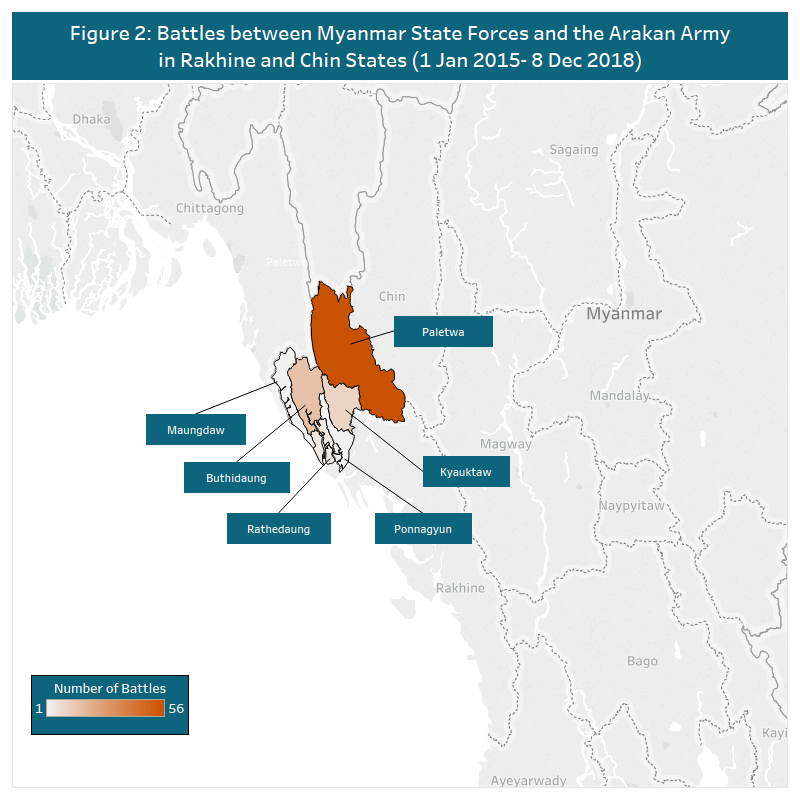

While a significant portion of the fighting between the AA and the Myanmar military occurs in Rakhine state, the majority of battles between the two have occurred in Paletwa township in Chin state which borders Rakhine state (see Figure 2). The poorest township in the poorest state in Myanmar, Paletwa is located off the banks of the Kaladan river, a key means of transit in the region. It is the site of the Indian government’s Kaladan Multi-Modal Transport (KMMT) project as well as other development projects (Tea Circle Oxford, 17 May 2018). Recent fighting between the AA and the Myanmar military in Paletwa has led to displacement and hardship for many villagers. It has also raised the specter of conflict between ethnic armed groups in the region, as the Chin National Front/Chin National Army (CNF/CNA), a signatory to the NCA, has suggested it will engage the AA if its actions continue to affect Chin civilians (Euro Burma Office, 3 July 2015).

Popular support for the AA has risen along with a growing Rakhine ethnic nationalism that is founded not solely in opposition to the Rohingya, but out of a distrust of the Burman majority. Earlier in the year, when a march in Mrauk-U, marking the anniversary of the fall of the Rakhine kingdom, was met with the police shooting and killing seven demonstrators, it exacerbated tensions in the region (The New York Times, 17 January 2018). The subsequent arrest of Dr. Aye Maung, the leader of the largest ethnic Rakhine political party, the Arakan National Party (ANP), on charges of supporting the AA also led to many demonstrations in the state (see ACLED’s piece on demonstrations in Myanmar this past year here). More recently, a man who released a balloon with the leader of the AA’s portrait on it wishing him happy birthday was sentenced to two years in prison under Article 17 (1) of the Unlawful Associations Act, a law that is often used to imprison those with contacts to groups deemed unlawful (The Irrawaddy, 27 November 2018).

With the recent by-elections showing a decline in the support of the NLD in ethnic regions (Myanmar Times, 5 November 2018), the ongoing peace process is likely to face more challenges. The growing number of military bases being built in Rakhine state also raises concern (Amnesty International, 12 March 2018). While talking peace, it is likely that conflict across the country, including in Rakhine and Chin states, will continue.