Boko Haram’s attack on Rann, a town in North East Nigeria on January 28th resulted in 60 reported fatalities and more than 30,000 people fleeing (Al Jazeera, 29 January 2019). The attack on Rann came just after the Multi-National Joint Task Force (MNJTF) – a coalition of forces from Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad, Niger, and Benin – withdrew from the town, leaving the Nigerian military in charge of providing security. There are reports that civilians were “apprehensive” about the withdraw and began leaving Rann even before Boko Haram attacked (ChannelsTV, 28 January 2019). Recent high profile attacks on targets like Rann and Nigerian military bases underscore the Nigerian military’s inability to contain the insurgency. Two weeks prior the same town was attacked by Boko Haram rebels still led by Abubakar Shekau – though the attack was originally attributed to the break-away faction lead by Abu al-Barnawi (The Defense Post, 17 January 2019).

Recent events in Rann underline the extent to which claims that the group has been defeated (Financial Times, 6 December 2018) and assertions about the group’s connections to transnational jihadist rebels (Perspectives on Terrorism, 2017), are both overstated. An assessment of Boko Haram’s activity since 2014 reveals remarkable continuity. Boko Haram remains a remarkably consistent and potent threat, driven by local dynamics.

Boko Haram’s Activities Over Time: Continuity in One of the World’s Most Deadly Conflicts

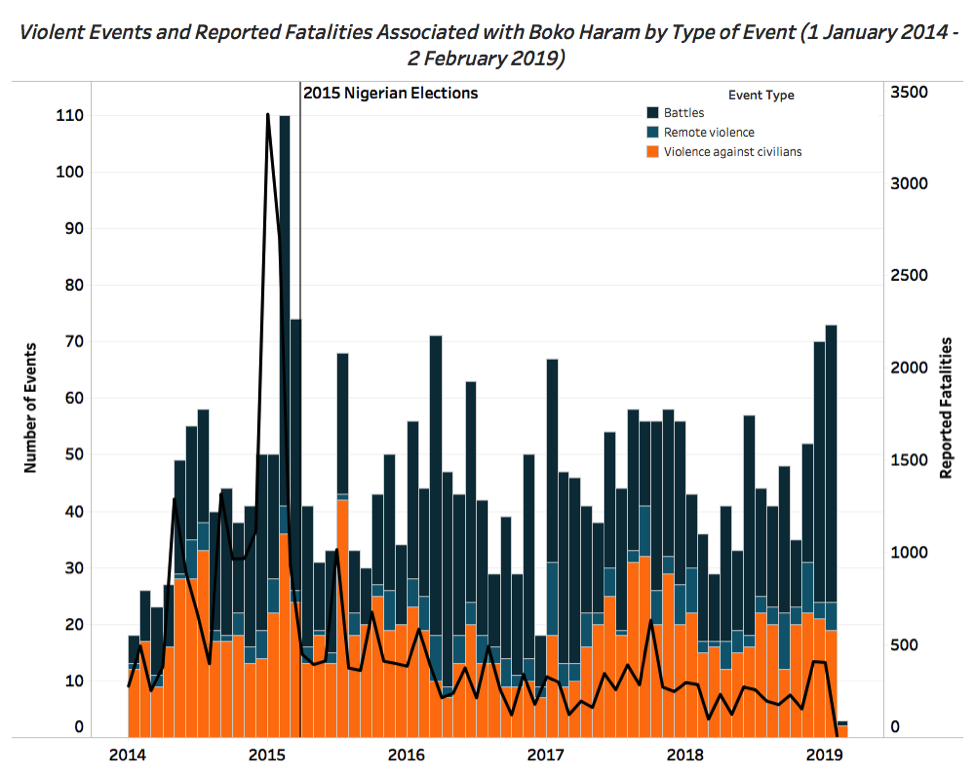

Between 2014 and present, Boko Haram has been responsible for more than 2,800 events and more than 31,000 reported fatalities, making it one of the world’s deadliest armed groups. 2017 was the most active year for the group, in which there were 621 events; in 2018 the number of violent events involving the group declined to 529. The government’s claims that the group is “defeated” are off-base (The Pulse, 25 December 2018). Boko Haram retains the capacity to engage in devastating attacks and has maintained a consistent level of activity since 2014, as demonstrated below.

One notable shift is the steep and steady decline in reported fatalities associated with the group, even as the number of attacks has fluctuated. There were more than 11,500 reported fatalities by the group in 2015, the deadliest year. By 2018 that number had fallen to approximately 2,700 reported fatalities.

Related to this trend is the decline in the lethality of Boko Haram’s violence. The group’s lethality has been on the decline since 2015, when the average number of reported fatalities per attack reached nearly 19; in 2018, the average lethality of each violent event involving Boko Haram was just under 5 reported fatalities.

Despite fluctuations in the group’s overall level of activity, its pattern of violence has remained remarkably consistent. Since 2014, about 40% of the group’s activities have been violence against civilians, 8% have been remote violence, and 52% have been battles, a distribution that has remained generally constant.

The most notable shift was between March 2016 and March 2017, when violence against civilians fell as a proportion of the group’s activity. This dip corresponds to reports of fragmentation within the group, as well as an increased military effort against the insurgents. The decline in civilian targeting lends credence to narratives that suggest that violence against civilians drove the leadership divide within the group that resulted in a breakaway faction from Boko Haram that sought to cultivate closer ties with the Islamic State (Congressional Research Service, 28 June 2018). This faction is frequently referred to as the “Islamic State West Africa Province” (ISWAP) and is led by Abu Musab al-Barnawi (BBC, 16 July 2018).

Fragmentation in Boko Haram (Deja Vu All Over Again)

Reports have often sensationalized the leadership divide, overemphasizing the extent to which foreign organizations exercise influence over Boko Haram and ignoring the intra-rebel and domestic influences that drive Boko Haram’s activities (Perspectives on Terrorism, 2018). One analyst claimed that “ISWA has asked IS for theological guidance on who it is lawful to attack,” suggesting that the group’s operations are driven by foreign actors (Reuters, 29 April 2018).

These narratives often overlook that Boko Haram has long been a cellular organization (Washington Post, 24 August 2016) and ignores Boko Haram’s history of fragmentation and reconciliation. In 2012 a group calling itself “Jama’atu Ansarul Muslimina Fi Biladis Sudan” (or “Ansaru”) lodged similar complaints as ISWAP’s Barnawi. Ansaru broke away from Boko Haram to operate independently. Similar to the reports that ISWAP has sought closer ties to ISIS, Ansaru reportedly sought closer ties with al Qaeda (BBC, 3 April 2016). This faction operated independently for a few years before fading into irrelevance, undermined by defections back to Boko Haram and the arrest of it’s top leader in 2016 (Reuters, 4 April 2016). Even after Ansaru broke away from Boko Haram, Mike Smith concluded that the organization is best understood “as an umbrella-like structure, with true organisation only at the very top” (Africa Check, 22 September 2014). This assessment remains relevant today in the face of a leadership division between Shekau and Barnawi; it may be best to merely consider these two factions as the most dominant cells in an insurgency, rather than considering the leadership divide an irrevocable split in the group.

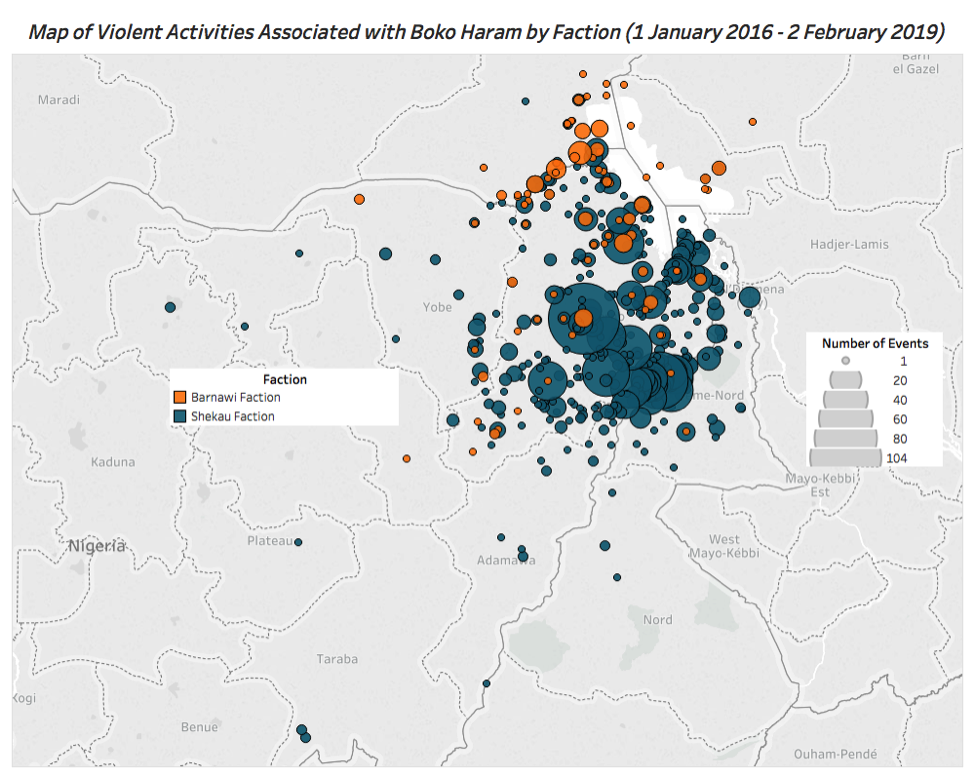

As compared to the faction of Boko Haram still lead by Abubakar Shekau (who took over after the group’s founder, Mohammed Yusuf, was killed by Nigerian security forces), units affiliated with Barnawi engage in fewer violent events. Only 9% of the violent events associated with Boko Haram have been attributed to the Barnawi faction since 2016. Of those events, Barnawi’s faction engages in less civilian targeting. Since 2016, 25% of their activity has been violence against civilians, as compared to 37% the violent events associated with other Boko Haram factions. Though there are differences in the operational profiles of the Barnawi faction and the Shekau factions of Boko Haram, these differences are more likely a function of where they operate than a result of international influence. As demonstrated below, Barnawi’s faction of Boko Haram is more active towards around the border with Niger, whereas the Shekau faction of Boko Haram is more active in Borno and Adamawa States, near Cameroon.

What Drives Changes in Boko Haram’s Violence?

Narratives that emphasize transnational jihadist influences on Boko Haram’s activities overlook more influential local drivers of the group’s violence. Political incentives and seasonal changes are both consistently associated with surges and declines in the group’s violence.

Political Drivers of Violence

Boko Haram’s most active and lethal period was in the lead up to the March 2015 elections. In February 2015 alone, there were 110 violent events associated with the group, resulting in nearly 2,700 reported fatalities. There has been a similar surge in the group’s activities ahead of the February 2019 elections. In January 2019, there were 73 violent events involving the group and 406 associated reported fatalities. Of note is that 71% of the violent events in January 2019 have been between Boko Haram and the Nigerian military — a significant change from the February 2015 shift, when such activities only accounted for 58% of the group’s activities. On at least five occasions in January 2019, Boko Haram militants attacked military bases in North East Nigeria. On January 1, Boko Haram overran military posts in Yobe and three other areas in Borno State.

Shifts like these highlight how the group’s activities are related to political developments in the country. Elections provide an opportunity not just for politicians to make their case to voters, but also for armed groups to demonstrate their relevance and undermine confidence in the state’s ability to provide protection. Nigeria’s looming elections on February 19th could explain the recent surge in violent activity.

Seasonal Patterns of Violence

The group’s activity also corresponds to seasonal changes. Many have noted an uptick in the group’s activities in the rainy season, which stretches from June to September (News24, 15 August 2018). During this period, washed out roads can make it difficult for the Nigerian military to navigate heavy equipment and access remote areas to combat the rebels. A disproportionate share of the group’s total number of violent events (32%) and violence against civilians (37%) occurs during those periods. Regardless of the outcome of the election, a surge in Boko Haram’s violent activity can be expected during the 2019 rainy season.

What does this mean going forward?

Fluctuations in the group’s overall levels of violence and the ways in which this violence manifests since 2014 appear to be driven largely by intra-insurgent dynamics, political incentives, and the seasons. Speculative accounts of the group’s violence being driven by the interests of transnational rebel groups overlook the extent to which the group’s activities have remained remarkably consistent since 2014. They also obscure the domestic drivers of Boko Haram’s violence, including elections and seasonal changes.

All of these patterns underline the extent to which the Nigerian military’s effort against Boko Haram has failed to undermine the group’s capacity to engage in violent activities. The events at Rann highlight the extent to which citizens do not and cannot trust the government to provide security. The Nigerian government and Boko Haram appear to be locked in a brutal stalemate that is likely to continue for a number of years.