Early on 26 February, India fighter jets crossed the Line of Control (LoC) dividing India and Pakistan, allegedly launching strikes on militant targets in Pakistan (The Economic Times, 26 February 2019).[1] The attack came 12 days after a suicide attack in the Kashmir’s Pulwama district reportedly killed dozens of Indian paramilitary troopers.

In order to understand how the actions of an armed non-state actor led to a dramatic escalation in hostilities between two nuclear powers, this analysis looks at demonstration activity in the aftermath of the Pulwama attack. It argues that India’s cross-border strike was forced by strong public engagement following the Pulwama attack rather than the attack meeting any specific operational needs in the Kashmir conflict.

The Pulwama Attack and Its Aftermath

On 14 February, a Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM) suicide bomber rammed a Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) convoy with an explosives-laden vehicle in Pulwama district of Jammu & Kashmir (J&K), killing at least 37 CRPF troopers (The Economic Times, 15 February 2019). The JeM is one of a number of separatist groups currently operating against the Indian state in J&K. Others include Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) and Hizb-ul-Mujahideen (HM). Indian authorities have long accused their Pakistani counterparts of harbouring and aiding militant groups in J&K — allegations that the Pakistani government has vehemently denied. The conflict over the contested Himalayan region has further fuelled the politico-social enmity between both countries as well as between the rest of India and J&K.

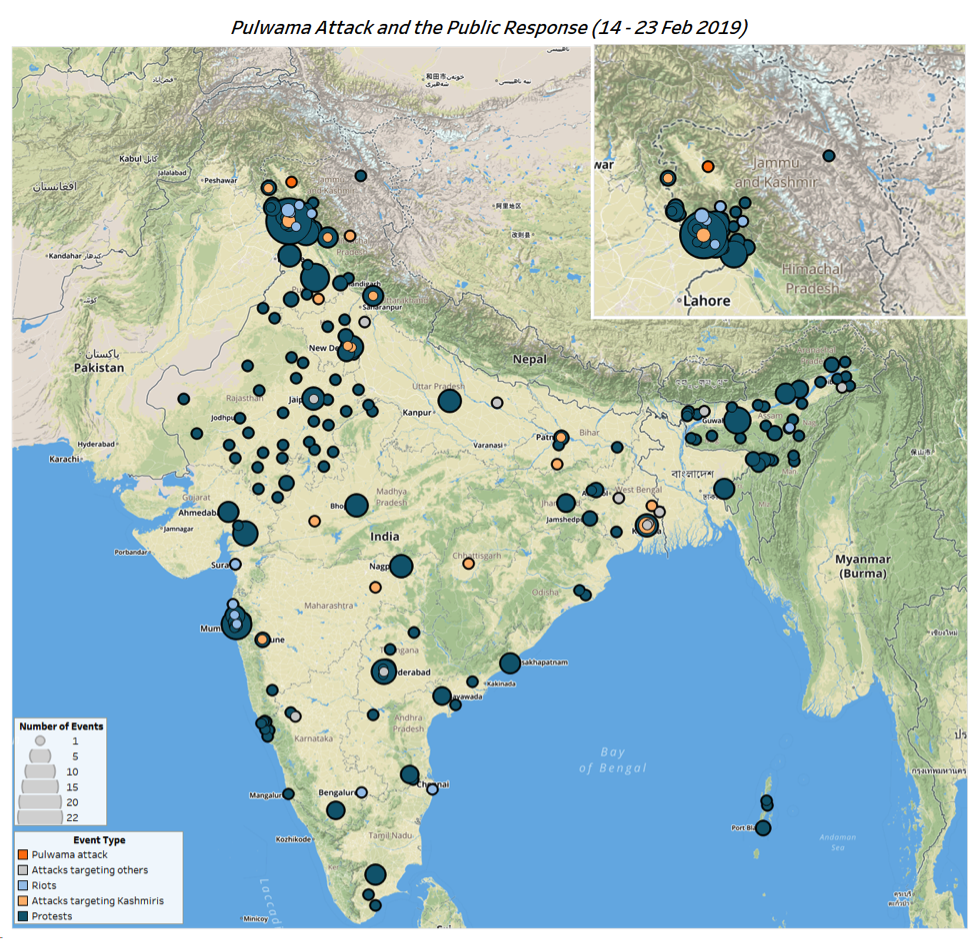

This latest attack sparked nationwide demonstrations, especially in North India, the northeastern states, and in major cities across the country. The map below shows the public reaction to the Pulwama attack and depicts how and where the Indian public engages with the Kashmir conflict. While demonstrations remained largely peaceful, large-scale rioting was reported throughout Jammu division, as highlighted in the inset map. Members of the Kashmiri community were also attacked by mobs of people seeking revenge for the attack; these mobs are often associated with Hindu right-wing groups, for whom Muslim-majority Kashmir represents a breach in the Hindu nationalist ideal of India. Additionally, several attacks targeted people that had been accused of activities that were deemed to be either anti-India, pro-Pakistan, or sympathetic to Kashmiris. Most incidents of mob violence were reported from either East or North India. In contrast, the response to the attack in Srinagar and in the wider Kashmir Valley was muted (see also inset map below), with a lack of demonstrations reported in what is one of the most demonstration-prone areas in India.

Linking Fatalities and Public Engagement with the Kashmir Conflict

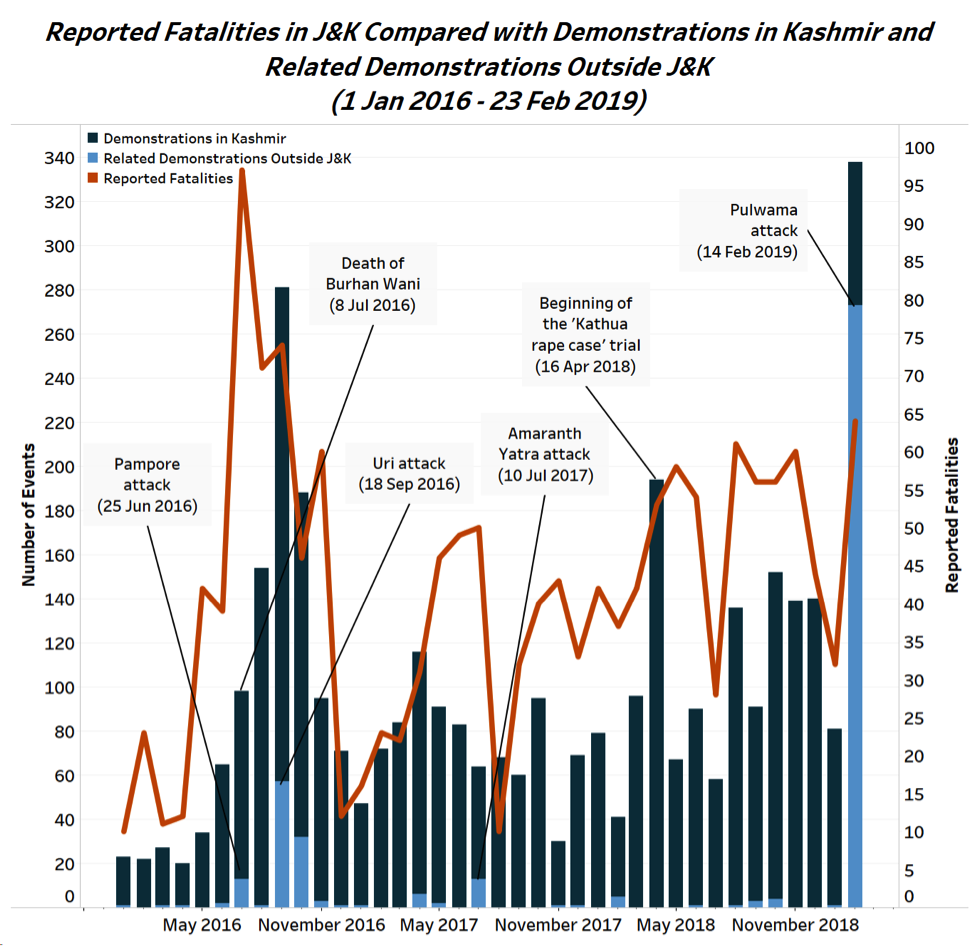

Differing reactions to the Pulwama attack point to a broader difference between how those inside Kashmir and those outside of the area respond to the Kashmir conflict. The highest number of fatalities stemming from the Kashmir conflict was recorded in 2018, pointing to an escalating intensity. In Kashmir, the largest number of demonstration events was recorded in 2018, matching the increase in reported fatalities that year. Specifically, demonstration activity of the Kashmiri population tends to peak in the aftermath of high profile events (see the navy blue bars in graph below) — such as in the aftermath of the killing of prominent HM commander Burhan Wani on 8 July 2016, or the commencement of the trial for the so-called ‘Kathua rape case’ on 16 April 2018. While the latter does not directly fall within the scope of the Kashmir conflict, the rape of a Muslim girl from the Bakarwal-Gujjar nomadic community further escalated existing ethno-religious tensions in the region (New York Times, 11 April 2018).

Meanwhile, outside of J&K, fewer demonstrations relating to the Kashmir conflict were recorded in 2018 than in either of the previous two years. Engagement of the wider Indian public is, therefore, seemingly not driven by the overall number of reported fatalities but rather by the identity of those killed; the Kashmir conflict only receives nationwide attention when high numbers of non-Kashmiris, especially security forces, are reported to have been killed in a singular event. The graph below shows a significant spike in demonstration events outside J&K (in blue) following the Pulwama attack as well as the second deadliest attack in recent years — the Uri attack on 18 September 2016, in which 17 army soldiers and four militants were reportedly killed (The Indian Express, 18 September 2016). Notable spikes in demonstration events are also evident following the Pampore attack on 25 June 2016, which resulted in the reported deaths of eight CRPF officers (The Indian Express, 26 June 2016), and the Amarnath Yatra attack, in which eight Hindu pilgrims were reportedly killed (Hindustan Times, 11 July 2017).

Future Actions and Military Solutions?

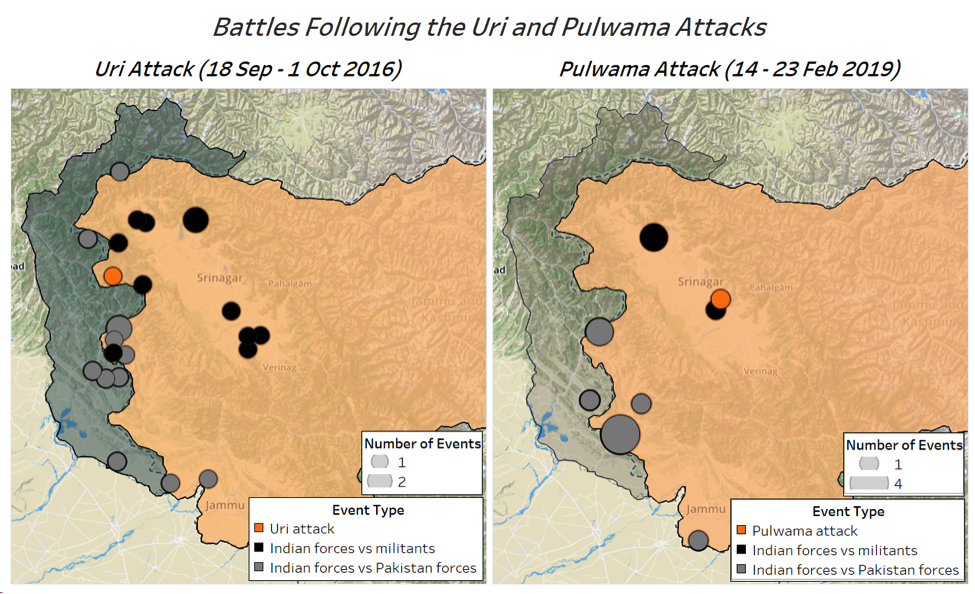

Whilst reported fatalities in J&K for 2018 eclipsed those of the previous two years, the large number of non-Kashmiri deaths in the Uri attack resulted in significantly more demonstrations in India than in 2017 and 2018 combined. This prompted the government to launch a series of cross-border incursions, known as ‘surgical strikes’, into Pakistan-administered Kashmir. As shown in the map below, these strikes occurred amidst wider engagements between Indian and Pakistani forces along the Line of Control (indicated by the broken line in the map below), as well as a series of clashes between militants and Indian forces. The strikes were alleged to have targeted militant camps in Pakistani territory, though the details remain unclear and Pakistan denies their occurrence (BBC News, 23 October 2016).

In similar fashion, India’s recent incursion was preceded by several clashes with militants, and sustained cross-border exchanges between Indian and Pakistani ground troops. Regardless of the veracity of the reports, the ‘surgical strikes’ entered into the popular narrative of the Kashmir conflict and provided precedence as well as an expectation for Indian military retaliation against Pakistan. With upcoming national elections scheduled for April/May of this year, a substantive response was further seen as a political necessity for the Narendra Modi-led Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government to hold on to power.

Whilst the Indian government has suggested that the surgical strikes were focused on eroding the ability of militants to infiltrate and carry out attacks in Kashmir (Ministry of External Affairs, 29 September 2016), JeM’s successful execution of the Pulwama attack less than three years later undermines this narrative. Indeed, India’s latest move is best seen as a response to internal engagement with the Kashmir conflict, rather than an attempt to undermine militant activities in J&K. Much like the surgical strikes before it, India’s latest operation may do little to stem the increasing death toll in Kashmir.

Notes:

[1] Any incidents of political violence or demonstration after 23 February will be featured in the data release on March 4.