This week, Indian voters started casting their votes in the 17th general election to elect a new Parliament (Lok Sabha). Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which had won a majority of the seats in the 2014 general elections, seeks a second term and has forged alliances with numerous regional parties. In a bid to defeat the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA), its principal rival, the Indian National Congress (INC), has also stitched up a coalition of allied parties. At the same time, several regional players, like the Trinamool Congress (TMC) in West Bengal and the Biju Janata Dal (BJD) in Odisha, have decided to contest independently.

With India being the second most populous country in the world, the general elections are the world’s largest democratic exercises. Stretched out over seven phases from 11 April to 19 May, nearly 900 million voters will be eligible to vote to fill 543 assembly seats (Economic Times, 13 May 2019). Elections of this scale come with various security challenges, including questions of voter fraud, corruption, and cyber security. The Indian government is also confronted with the challenge of providing hard security in view of multiple and complex security concerns ranging across international conflicts, domestic rebel groups, and violent political rivalries.

The Indian Election Commission (EC) has identified pockets vulnerable to electoral violence – so-called sensitive or critical polling stations – as part of its effort to ensure and help secure free and fair elections. Over 500,000 security personnel drawn from seven central paramilitary and police forces will be deployed across the country during the seven-phase election period. Despite the number of polling stations in 2019 rising by 10% from 2014, about 10% fewer security forces will be deployed in 2019 owing to heavy troop deployment at the border in view of heightened tensions between India and Pakistan in recent weeks (Economic Times, 13 March 2019).

This analysis piece seeks to identify the key drivers for violence and electoral issues in India’s most vulnerable areas and in doing so to provide a better understanding of the upcoming general elections. The areas identified as most vulnerable to electoral violence are those that are the site of ongoing armed conflicts, namely (1) Jammu & Kashmir; (2) the “Red Corridor” states; (3) the northeastern states; as well as (4) West Bengal and Kerala, two states with significant levels of political violence. As ACLED data coverage of India currently extend back only to 2016 and do not cover the 2014 general elections, data are drawn from the most recent state and local body elections for comparison here. Wherever possible, data from state assembly elections are used as a reference point, while data from local body elections are used in those states which have not held state elections since 2016.

I. Conflict in Jammu & Kashmir

The state of Jammu & Kashmir (J&K) has been a site of conflict since 1947. As its only Muslim-majority state, India’s administration of J&K has long been a source of tension both internally and between India and Pakistan. This tension manifests violently through sporadic outbreaks of cross-border violence between Indian and Pakistani forces, as well as the activities of militant groups fighting against the Indian state, such as Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM), and Hizb-ul-Mujahideen (HM). The Indian central government also faces stiff opposition from large segments of the local population, reflected in the high numbers of anti-government protests and stone-pelting incidents targeting security forces.

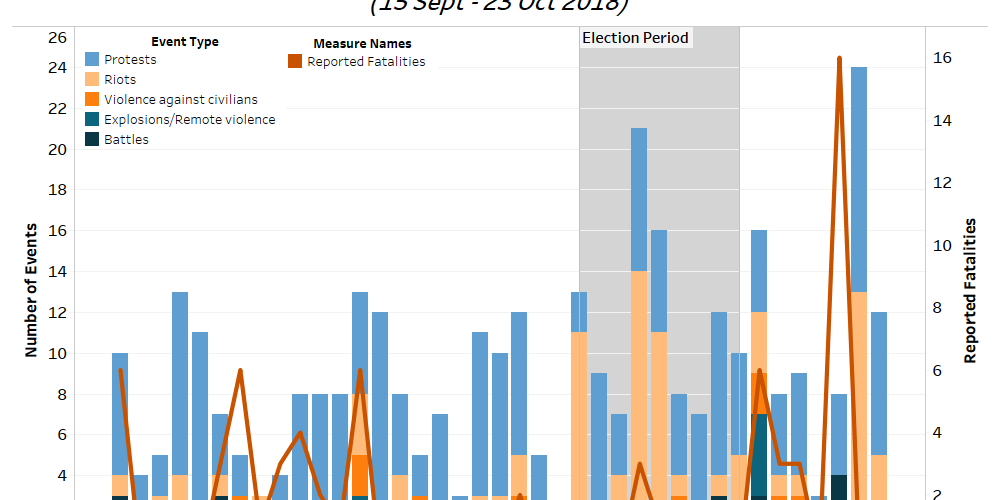

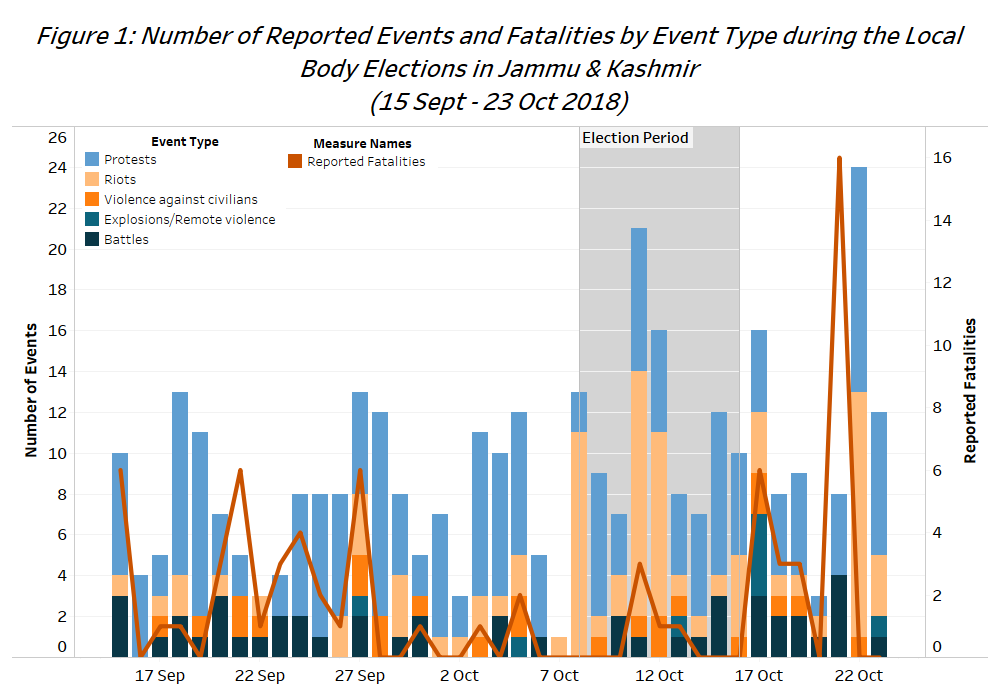

In 2018, local body elections were held in all districts of Jammu & Kashmir. Figure 1 and 2 below show the number of reported events and fatalities by event type as well as a breakdown of the actors involved in organized violence. The time period depicted in Figure 1 ranges from the date of the announcement of the elections days to seven days after the last day of voting. About half of the reported events during that time period were protests, one quarter were riots, and one quarter were events of organized violence including battles, targeted attacks on civilians, as well as explosions and remote violence. The reported number of rioting events (in peach) increased during the election period while the number of battles (in navy) and reported fatalities (maroon line) spiked in the seven days after the last day of voting.

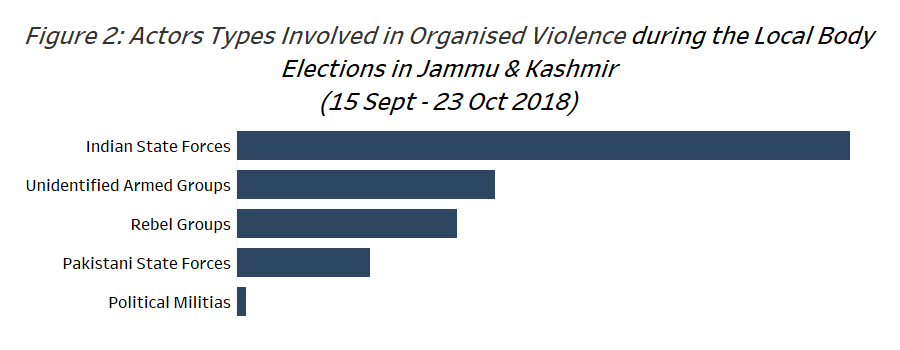

With regard to the actor types involved in political violence during the 2018 local body election period, Indian state forces – including police and military – were involved in most reported organized violence events. State forces are followed by unidentified armed groups (UAG), identified rebel groups, and Pakistani state forces while organized violence events perpetrated by identified political militias were rarely reported during the elections in Jammu & Kashmir (see Figure 2 below).

A record number of fatalities were reported in Jammu & Kashmir in 2018; so far reported fatality figures for 1 January to 6 April 2019 surpassed those of 2018 for the same time period. Tensions in Jammu & Kashmir increased following the Pulwama attack on 14 February that left at least 40 Indian state troopers dead (for more on this, see this ACLED piece). The attack was followed by Indian and Pakistani aerial strikes on each other’s territory as well as a surge in counter insurgency operations in Jammu & Kashmir. The Pulwama attack has also put national security at the forefront of the national discourse in the lead up to the elections and is seen as the key factor determining the election outcome.

At the state level, governance and the conflict with the central government over issues of political autonomy are integral. There has been no representative government in the state since June 2018 when a coalition government between the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the regional People’s Democratic Party (PDP) collapsed. The central government has also cracked down on socio-religious bodies in the state by announcing bans, raiding their offices, and arresting their members. In addition, the central government has arrested local leaders who are pro-independence, many of whom are reportedly popular among locals. On the question of regional autonomy, the BJP has made the abrogation of Article 370, which grants Jammu & Kashmir a special status – including a separate constitution and flag – a key electoral issue. Related to this, the BJP is also committed to help facilitate the return of displaced Kashmiri Hindu pandits to the state. Disenchantment with the Indian rule over the region has been growing, arguably inciting many youths to join the militancy movement against the Indian state (NDTV, 7 May 2018).

The general elections will be spread out over five phases in Jammu & Kashmir. With tension already at an all time high and even greater military presence in the state, it is likely that voting will be accompanied by significant levels of violence, especially clashes between stone-pelting rioters and security forces.

II. The Naxalite-Maoist Insurgency

Left-wing extremist groups have been engaged in a longstanding insurgency against the Indian state in the so-called “Red Corridor” area, which covers a vast territory in central, eastern, and southern India. Areas affected by the Naxalite-Maoist insurgency are parts of Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Bihar, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, West Bengal, and Uttar Pradesh. The reasons behind this insurgency are myriad and complex. States like Jharkhand, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Odisha languish at the bottom of the country’s Human Development Index (Global Data Lab). These states are rich in mineral wealth and are often the sites of mining activities by major corporate players. In the last five decades, over 50 million people in India have been displaced for development projects; many of the displaced populations are from this region, belonging to indigenous tribal communities (IndiaSpend, 17 June 2014). At the same time, these communities have struggled to gain access to property rights.

Maoist rebels have opposed all such activities involving land acquisition in the “Red-corridor” states and hence, have enjoyed support from some sections of the local population. Maoist rebels denounce the legitimacy of the Indian state and, as such, Indian democratic institutions such as elections. Maoist rebels often call for the boycott of elections and do not shy away from using violent means to enforce their boycotts. Attacks targeting politicians, polling stations, polling staff, and journalists are common during election periods. Typically, Maoist rebel activity as well as anti-Maoist operations by state forces significantly increase in the lead up to elections (for more on this, see this ACLED infographic).

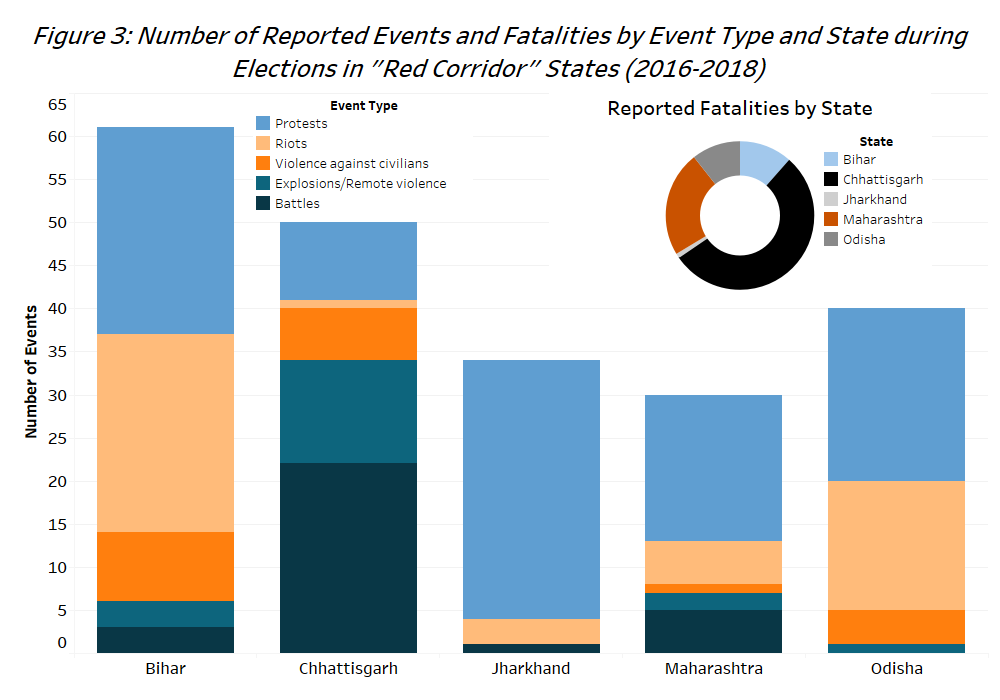

Elections were held in several of the states most affected by left-wing extremism in the 2016-2019 period. State assembly elections were held in Chhattisgarh in late 2018. Rural local body elections were held in several districts of Bihar in 2016, and in Odisha and Maharashtra in 2017; Municipal Corporation and Council elections were held in several districts of Jharkhand in 2018. Figure 3 below depicts the reported number of events by event type for each state during their respective election periods, starting from the date of announcement of the elections days to one week after the last day of voting. The donut chart in the right upper corner shows the number of reported fatalities by state during the same time period.

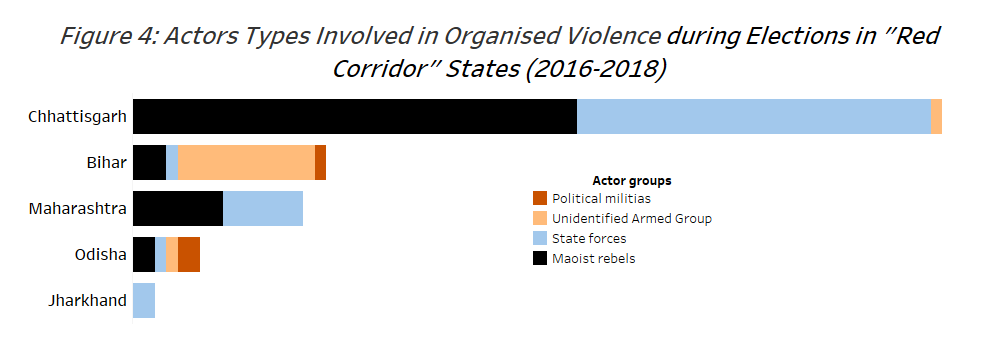

Significant levels of organized violence (in teal, orange, and navy on the graph) were recorded from Chhattisgarh, the state with the highest levels of Maoist violence in general (see Figure 4 below). Figure 4 shows that Maoist rebels and state forces were the main actors involved in organized violence in Chhattisgarh and Maharashtra, while political militias were not active during the same time period. With Maoist rebels still being active, greater activity by political militias and unidentified armed groups was recorded in Odisha and Bihar, inferring that violent rivalries between members of political parties are more common in those states. No events involving Maoist rebels were recorded during the 2018 Municipal Corporation and Council elections in Jharkhand, even though elections were held in many of the districts affected by left-wing extremism.

In the lead up to the 2019 general elections, there has already been an escalation of conflict in the “Red Corridor” area. In February this year, the Supreme Court ordered (now put on hold) the eviction of 1.89 million people, most of them tribals, living on forest land (Business Standard, 21 February 2019). While the order has been put on hold, the specter of such displacement looms large over the elections. While state forces launched anti-Naxal campaigns leading to arrests and the raids of several rebel camps, Maoist rebels too stepped up their attacks against security forces and the local population. In the latest such incident, a local BJP lawmaker and four members of his security detail were killed when rebels triggered an improvised explosive device in Chhattisgarh’s Dantewada district (The Hindu, 9 April 2019). So far, Maoist outfits have also issued calls for election boycott in Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Kerala, and Maharashtra (Deccan Herald, 13 March 2019). It is likely that insurgency violence will further intensify in the coming weeks.

III. Violence in Northeast India

The northeastern region is comprised of the seven states of Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, and Tripura. The region’s geographic and cultural distance from the rest of the country, as well as its specific socio-cultural characteristics and ethnic diversity, have created a complex security environment involving numerous actors. The Indian state has been dealing with a large number of insurgent groups that demand independence or a substantial level of autonomy since 1950. While incidents of armed violence have been in decline over recent decades, protest movements by the local population have been growing stronger. A key issue, having led to significant civil unrest in recent times, is immigration policy and the conflict between the local indigenous and migrant population.

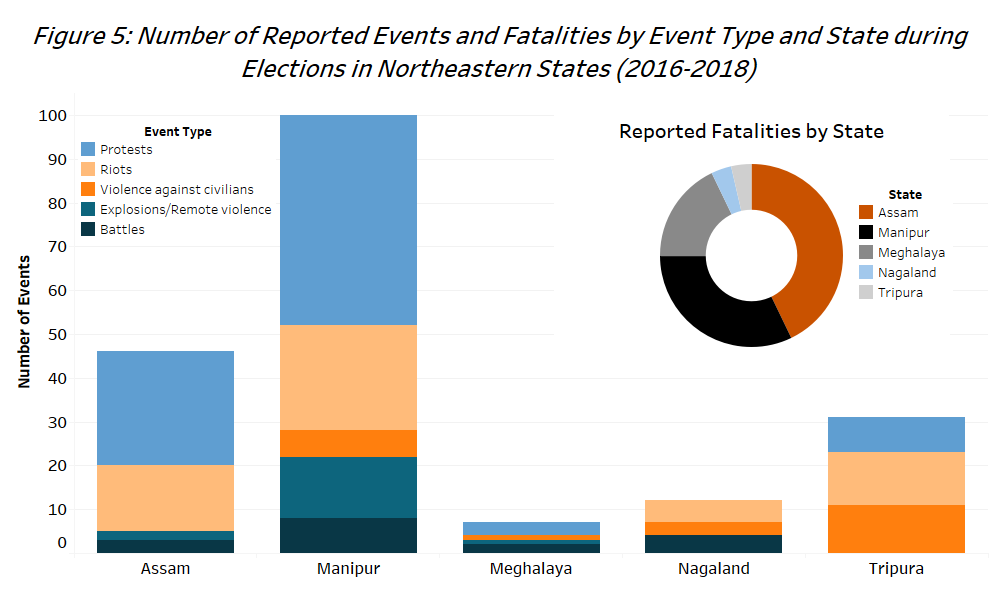

Elections were held in some of the seven northeastern states during the 2016-2019 period. State assembly elections were held in Assam in 2016, in Manipur in 2017, and in Meghalaya, Nagaland and Tripura in 2018. Figure 5 below depicts the reported number of events (graph) and fatalities (donut chart) by event type for each state during their respective election periods, starting from the date of announcement of the election days to one week after the last day of voting. Out of all five states, the highest number of organised violence events (navy, teal, and orange on the graph) were recorded in Manipur, while reported fatalities were the highest in Assam (maroon on the donut chart). All states but Meghalaya had significant levels of rioting (in peach on the graph) during the election period; targeted attacks on civilians (in orange on the graph) were most prevalent in Tripura.

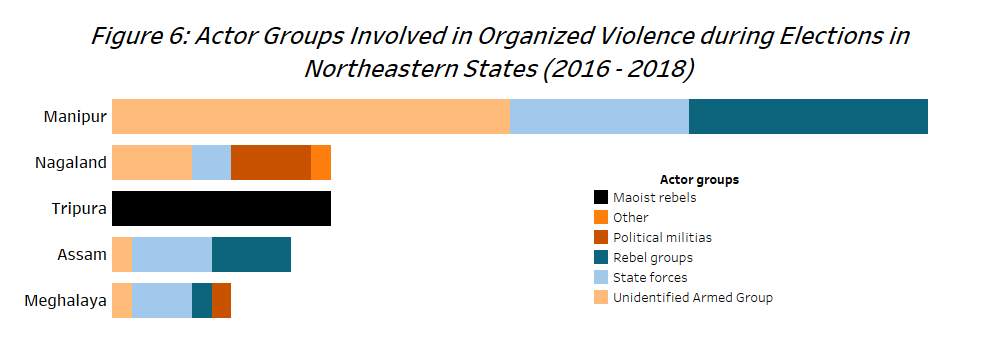

With regard to the actor types involved (see Figure 6 below), rebel groups (in teal) were most active in Manipur followed by in Assam and Meghalaya, while events involving identified political militias (in maroon) were only reported in Nagaland and Meghalaya. Maoist rebels (in black) were extremely active during the state elections in Tripura, being involved in all reported political violence events in that state.

In the lead up to the 2019 general elections several armed clashes and targeted attacks on civilians involving both rebel groups and political militias have been recorded so far this year. Electoral violence is most likely to be reported in the states of Manipur, Tripura, and Assam. In addition, protest movements against the state government are likely to pick up again following a few weeks of decreasing demonstration levels. A key issue is likely to be the National Register of Citizens (NRC), meant to identify undocumented immigrants, and the Citizenship Amendment Bill, which would grant citizenship rights to non-Muslim immigrants. Both are part of the BJP’s recent efforts to amend India’s citizenship laws which have led to significant civil unrest in Northeast India in late 2018 and early 2019 (for more on this, see this ACLED infographic).

IV. Violent Political Rivalries

Acts of low-intensity violence are numerous and are part of India’s electoral process at all stages, from the nomination of candidates to campaigning, voting, and following the declaration of results. A prime reason for the high levels of political violence is the increasing “criminalization of politics” in India. For instance, one in three Members of Parliament are reported to have a criminal case pending against them (Economic Times, 1 April 2019). Often, such politicians employ strong-arm tactics against both party-internal rivals and rival candidates from other political parties. To add to this, India’s political parties are opaque in their functioning and this is best exhibited during election periods, especially around deciding on the party’s list of fielded candidates. Disgruntled candidates, who have not been chosen for a party ticket, and their supporters, often resort to violence against factional rivals and the party establishment.

This time, both the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and opposition parties have eagerly sought alliances with other, smaller regional parties. Since alliance partners put up joint candidates, the number of political aspirants who are denied tickets has increased, leading to acts of violence by political workers (Hindustan Times, 2 April 2019; NDTV, 11 April 2019).

West Bengal and Kerala are two states with long histories of violent political rivalries. In West Bengal, the rivalry between the Trinamool Congress Party (TMC), currently in power at the state level, and the BJP, currently ruling the central government, has led to significant poll-related violence in the past (for more on this, see this ACLED piece). Until recently, the TMC shared a similar rivalry with the Left Front, namely the Communist Party of India (Marxist), the Communist Party of India, the All India Forward Bloc and the Revolutionary Socialist Party – an alliance of Left parties that was in power in the state for over three decades. Meanwhile in Kerala, political violence takes place along the fault line of the left-right divide in the state. The main actors involved are the left-wing Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI-M) and the right-wing, Hindu nationalist Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). Brutal tit-for-tat street killings have reportedly left at least 575 people dead since 1957 (The Hindu, 17 April 2019).

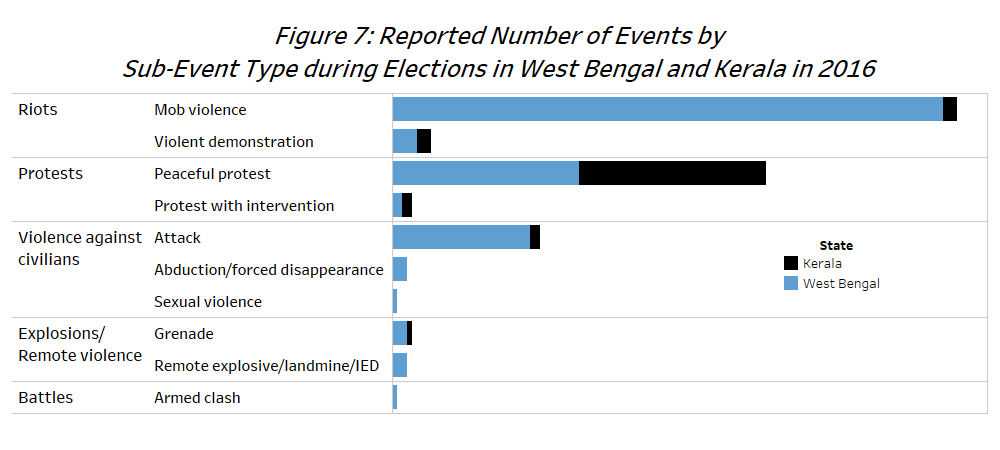

State assembly elections were held in both West Bengal and Kerala in 2016. Figure 7 below shows the number of reported events by sub-event type for both states during the respective election period. The elections in West Bengal were significantly more violent than the elections in Kerala, with not only more events being recorded in the former but also higher levels of organized violence. Attacks on civilians in West Bengal also included incidents of sexual violence as well as abductions and forced disappearances. The main sub-event type recorded during the election period, however, was mob violence, showing West Bengal’s violent electoral process that is dominated by clashes between party workers and spontaneous attacks and political rivals.

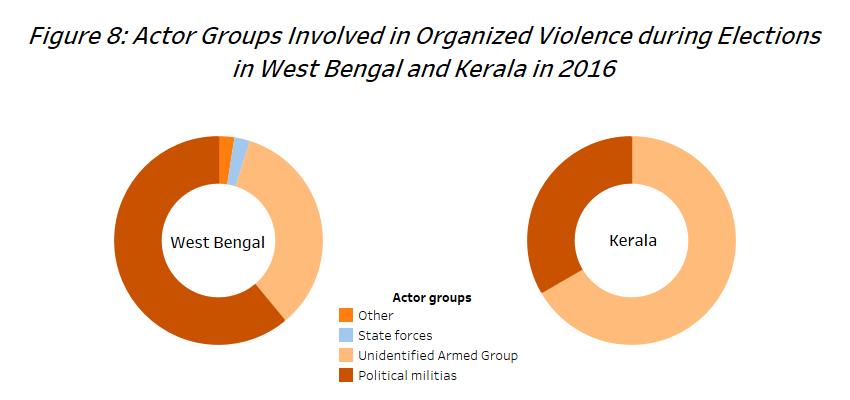

In Kerala, elections remained largely peaceful. Peaceful protests made up the largest number of reported events followed by isolated incidents of mob violence, violent demonstrations, grenade attacks, and attacks on civilians being recorded during the election period. In both states, political militias (in maroon) and UAGs (in peach) are the vast majority of actors involved in organized political violence during the election period (see Figure 8 below).

Several incidents of armed clashes, explosions and remote violence, and targeted attacks on civilians have so far been recorded in both West Bengal and Kerala in the lead up to the 2019 general elections. In West Bengal, the BJP is looking to make inroads into, what has so far been, the TMC’s stronghold. Communal tensions, allegations of corruption against the TMC’s leaders, and the BJP’s promise to implement the National Register of Citizens (NCR) in the state are some of the key issues dominating the electoral discourse in the state. In Kerala, the BJP has been aggressively campaigning against the ruling Left parties-led United Democratic Front (UDF) alliance over the issue of violence against the UDF’s political rivals, especially the BJP’s political workers. The elections might lead to an increase in political violence in the state in the coming weeks.

V. Conclusion

India’s internal security has traditionally faced challenges during election periods. The law and order situation remains sensitive in the regions noted above despite the security arrangements. In addition to the various rebel groups and political militias opposing the electoral process, political violence might also increase because of alliances between different parties fielding joint candidates. As a result, fewer candidates get to contest the elections, resulting in disenchantment among political workers. These myriad factors mean that the specter of political violence looms large over the 17th general elections. It is likely that significant levels of political violence will be reported from India’s most vulnerable areas as political actors and rebel groups pursue their agendas with violent means.