In Yemen, nearly five years of conflict have contributed to an extreme fragmentation of central power and authority and have often eroded local political orders. Local structures of authority have emerged, along with a plethora of para-state agents and militias at the behest of local elites and international patrons. According to the UN Panel of Experts, despite the disappearance of central authority, “Yemen, as a State, has all but ceased to exist,” replaced by distinct statelets fighting against each other (UN Panel of Experts, 26 January 2018).

This is the first report of a three-part analysis series exploring the fragmentation of state authority in southern Yemen, where a secessionist body – the Southern Transitional Council (STC) – has established itself, not without contestation, as the “legitimate representative” of the southern people (Southern Transitional Council, 7 December 2018). Since its emergence in 2017, the STC has evolved into a state-like entity with an executive body (the Leadership Council), a legislature (the Southern National Assembly), and armed forces, although the latter are under the virtual command structure of the Interior ministry in the internationally-recognised government of President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi. Investigating conflict dynamics in seven southern governorates, these reports seek to highlight how southern Yemen is all but a monolithic unit, reflecting the divided loyalties and aspirations of its political communities.

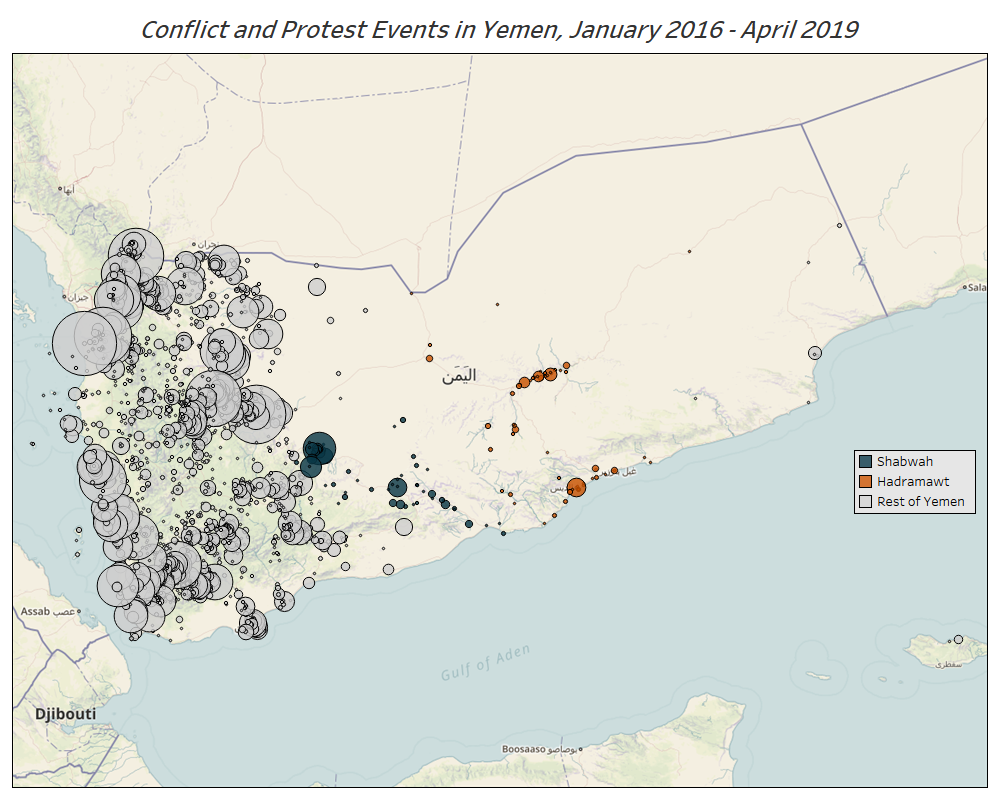

This first report focuses on the oil-producing regions of Shabwah and Hadramawt (highlighted in the map below). Both governorates have long enjoyed a high degree of autonomy from the central government but have been struggling to invest their oil and gas revenues into local development projects. Alongside an endemic presence of Islamist militants affiliated with the local branch of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), a fragile security situation has exacerbated tensions between the state and the local authorities.

Shabwah

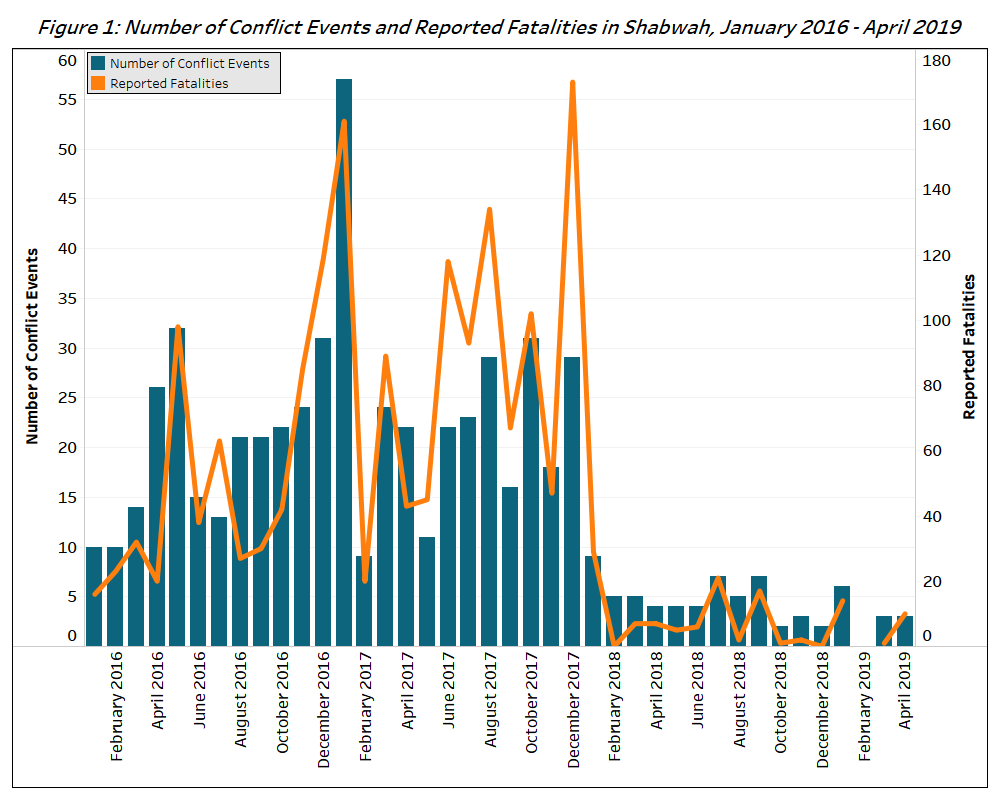

Between 2015 and 2017, Shabwah was one of the central frontlines in the conflict between Houthi-Saleh forces and Hadi loyalists. A largely tribal territory with little penetration from the central government, Shabwah was a long-time stronghold of Saleh’s General People’s Congress (GPC). The co-option of tribal shaykhs and other influential local elites made it easier for Saleh and the then-allied Houthi forces to overrun the provincial capital Ataq in April 2015 (Al-Jazeera, 9 April 2015). Although coalition-backed pro-Hadi troops retook Ataq only four months later, Houthi-Saleh forces continued to control the westernmost districts of Bayhan and Usaylan, which lied along profitable smuggling routes (Salisbury, 20 December 2017). The Yemeni army, largely consisting of Hadi-aligned brigades, and allied local fighters eventually recaptured Shabwah in December 2017, just weeks after the crumbling of the Houthi-Saleh alliance culminated in the assassination of the former president and his long-time Shabwani collaborator Arif Al-Zuka. Following the end of the hostilities, the security situation in Shabwah improved markedly, as illustrated by the number of reported fatalities, which decreased from 1,092 in 2017 to 97 in 2018 (see Figure 1).

In addition to its centrality in the civil war, Shabwah has been home to a prolonged insurgent campaign by AQAP. By February 2016, AQAP militants had captured the towns of Habban and Azzan, southeast of the provincial capital. The group has typically engaged in attacks against army and security forces, shying away from directly confronting the larger and better-equipped local tribes, but instead attempting to penetrate tribal structures through marriages and financial ties (Radman, 16 April 2019). According to tribal expert Nadwa Al-Dawsari, tribes have long resisted AQAP fearing that its presence could stoke local conflicts and escalate counter-terrorism operations (Al-Dawsari, February 2018).

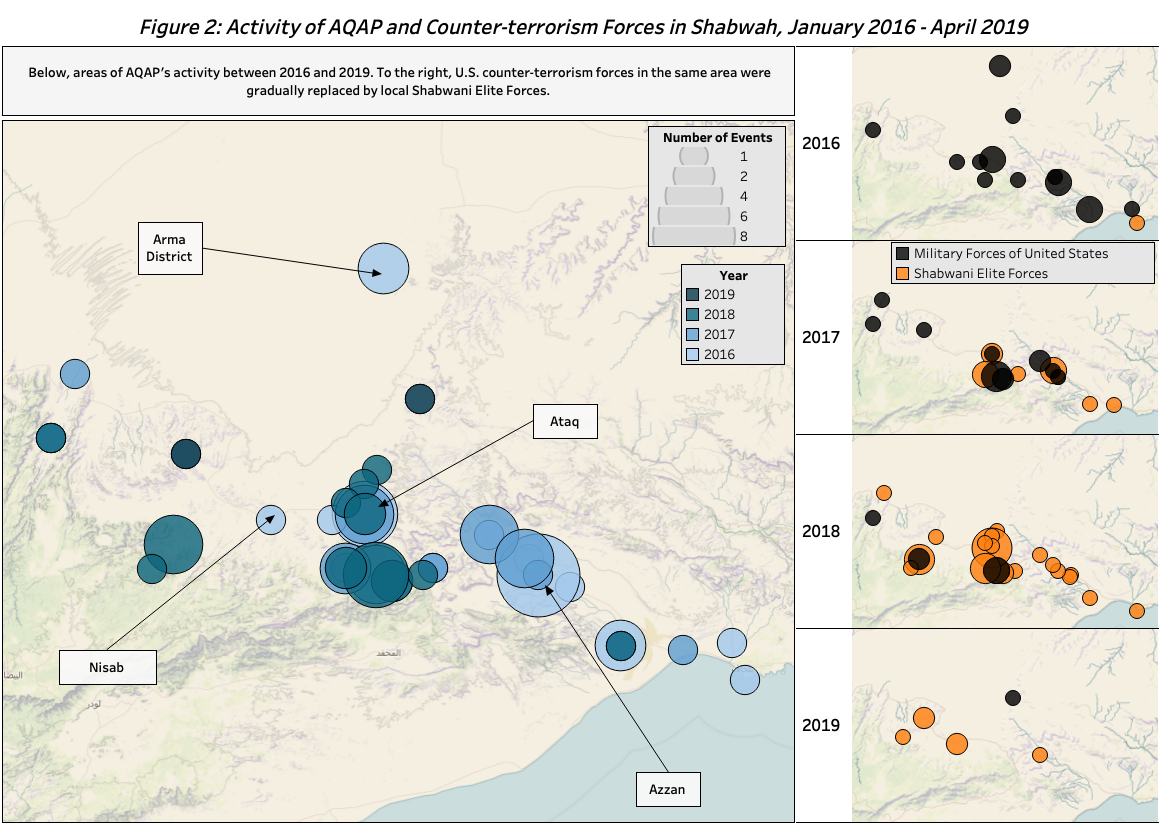

The United States and the UAE-trained Shabwani Elite Forces conducted several counter-terrorism operations that have succeeded in inhibiting AQAP’s activity in Shabwah, and further confined the militants in the province’s northern districts where they maintain ties with local tribes (Radman, 16 April 2019). Yet the US-led drone strikes claimed an increasingly high number of civilian fatalities, while the expanded role of UAE-backed military units has reignited tensions between the Islah bloc and the secessionist STC in the region. The data illustrated in Figure 2 show the changing spatial patterns of AQAP’s violent interactions recorded by ACLED between January 2016 and April 2019, along with the evolution of counter-terrorism activity.

These data highlight two main trends. On the one hand, the frequency of US-led strikes has dwindled since 2016, while the Shabwani Elite Forces have been involved in an increasing number of events during the same period. This trend seems to indicate that the US has scaled down its role in the fight against AQAP in Shabwah while leaving the leadership to locally recruited military units. After President Trump relaxed counter-terrorism rules in 2017 reducing civilian oversight on drone strikes (New York Times, 12 March 2017), civilian fatalities surged dramatically in Shabwah, with at least 12 people reported not to be AQAP operatives killed in such operations in 2017 alone. This military escalation was therefore set to backfire, further alienating the tribes and pushing them closer to AQAP.

On the other hand, the map illustrates how the Shabwani Elite Forces have extended their territorial outreach across the governorate. Over the past two years, UAE-backed army units were deployed in southern Shabwah, Azzan, As Said, Ataq and, more recently, in Habban, Markhah and Usaylan under the pretext of conducting counter-terrorism campaigns against militants (Al-Ittihad, 8 January 2019; Al-Mashareq, 22 January 2019; Sky News Arabia, 26 March 2019). Consisting of around 6,000 troops, the Shabwani Elite Forces largely recruit among local tribesmen, in attempt to consolidate tribal loyalties and provide jobs to the unemployed local youth among which AQAP also thrives (Radman, 16 April 2019). In addition to providing training, the UAE has launched local development projects aimed at restoring crumbling civilian infrastructure, for which locals accuse state neglect (New York Times, 7 October 2017).

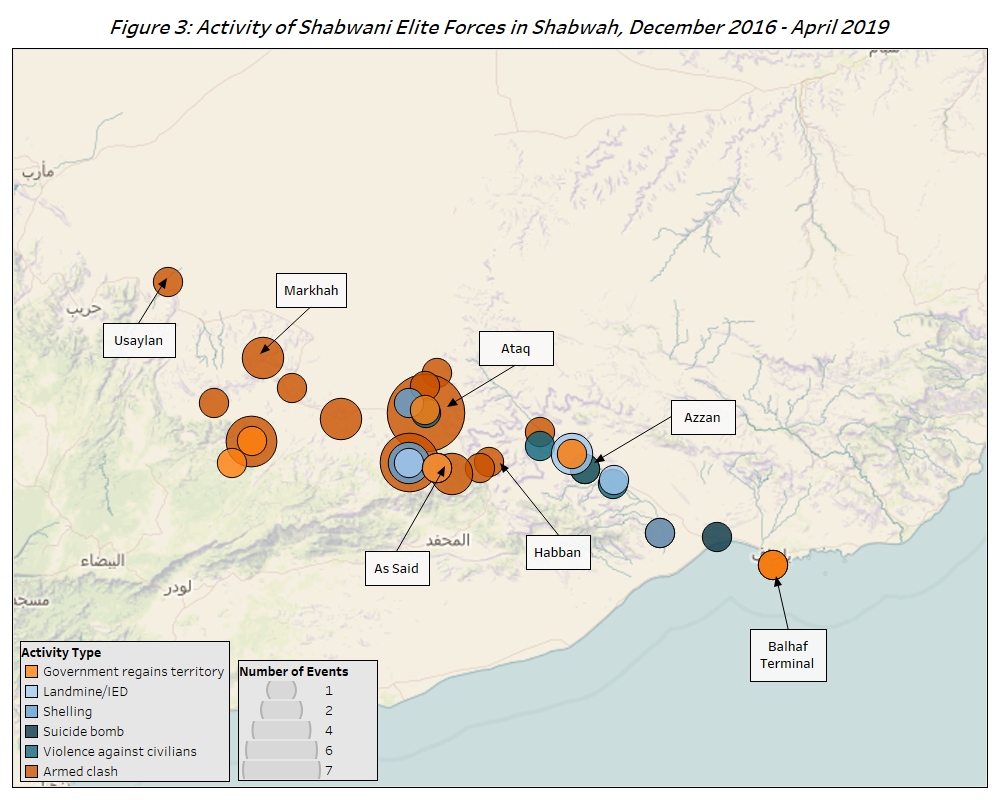

The UAE’s increasing involvement in Shabwah has resulted in upsetting the tribal order that regulate local socio-political dynamics. Although the Shabwani Elite Forces were designed as “a pan-tribal, local militia”, the UAE disproportionately recruited troops among the region’s smaller tribes, most notably the Belabid, Bani Hilal, Bilharith, and Al-Wahadi (Yemen Shabab, 12 August 2017; Heras, 14 June 2018). This preferential treatment, however, has generated frictions with Shabwah’s largest tribal grouping, the influential Al-Awlaqi confederation, accused of maintaining a non-confrontational relationship with AQAP. Amid these increasing tensions, the Shabwani Elite Forces were also reported to engage in a campaign of arbitrary detentions and torture of local residents, including several Awlaqi tribesmen (SAM Rights & Liberties, 11 August 2017; Masa Press, 12 August 2017; Mwatana, 19 March 2019). Reports of recent clashes in Nisab between tribesmen affiliated to different units of the Elite Forces further highlight the potential risks of unsettling the complex tribal environment in which they operate (Aden Post, 13 March 2019). Figure 3 maps the activity of the Shabwani Elite Forces since 2016.

Additionally, tensions have heightened around the oil production sector, amid growing popular discontent with corruption and allegations of economic appropriation by Northern investors (Twitter, 6 September 2018; Aden Al-Ghad, 16 January 2019). In January, Belabid tribesmen blockaded the passage of oil tankers outside an Austrian-run oil facility in Arma, northern Shabwah, sparking clashes with army forces guarding the site (Al-Masdar, 20 January 2019). The tribesmen – a major contributor to the Shabwani Elite Forces – lamented the limited redistribution of oil revenues and demanded that they are granted concessions in the lucrative delivery of crude oil from the facility, which resumed production last year under the Austrian company OMV (Österreichische Mineralölverwaltung). A few weeks earlier, accusations of corruption led Shabwah governor Mohammed Saleh bin Adiu to issue an arrest warrant for Saleh Ali Bafayadh, director of the local branch of the government-owned Yemen Oil Company. A former head of the anti-corruption committee in Shabwah, bin Adiu threatened to resign in March after denouncing government pressures to mollify his anti-corruption agenda, only to retract after receiving support from President Hadi (Al-Masdar, 6 March 2019). Bin Adiu is an influential figure in Shabwah, with connections to Hirakis and local tribal elites despite his controversial affiliation with Al-Islah.

Shabwah is also one of the sites of the wider confrontation between the central government and the secessionist STC, whose arc of influence spans across southern Yemen (ACLED, 10 October 2018). There are fears that the UAE is using its local proxies to sow divisions and push their anti-Islah agenda in the governorate, which is part of the Marib-based 3rd Military District led by Vice President Ali Mohsin Al-Ahmar. Accusations raised by STC representatives about the alleged presence of “terrorists” active in Ataq and Bayhan areas, where Al-Islah retains a strong presence, seem to point in this direction (International Crisis Group, 22 February 2019). Although sporadic clashes between forces loyal to the Hadi government and to the STC, respectively, have occurred in recent months (BuYemen, 18 December 2018), these have not turned into an all-out military confrontation for control of the governorate. However, concerns about a possible violent escalation remain high, and extend to the neighbouring governorate of Hadramawt.

Hadramawt

While it was spared from any Houthi incursions, the governorate of Hadramawt made the headlines during the current Yemen conflict when AQAP took over its capital, Mukalla, in April 2015. Exploiting the security breakdown that followed the ousting of President Hadi, the organisation presented itself as a Sunni bulwark against the Shi’a Houthi threat, and managed to run Hadramawt’s capital for an entire year (The Independent, 17 August 2018). It gradually laid down roots in the city, capitalising on the grievances of a population that had long been marginalised by the central authorities, all the while “taking a relatively accommodating and flexible approach toward the social imposition of its ideology” (Radman, 16 April 2019).

The control of Yemen’s third largest port and the country’s fifth largest city, with a population of around 500,000, arguably allowed the organisation to become “stronger than at any time since it first emerged almost 20 years ago”; helped by daily revenues from port customs amounting to $2 million, AQAP operated as a quasi-state in Mukalla, providing its residents with basic services like water and electricity (Reuters, 5 April 2016). From January 2016 until the ousting of AQAP militants from the city in April 2016, ACLED data show that Mukalla was the second district in Yemen with the most AQAP activity, reflecting the organisation’s grip on the city.

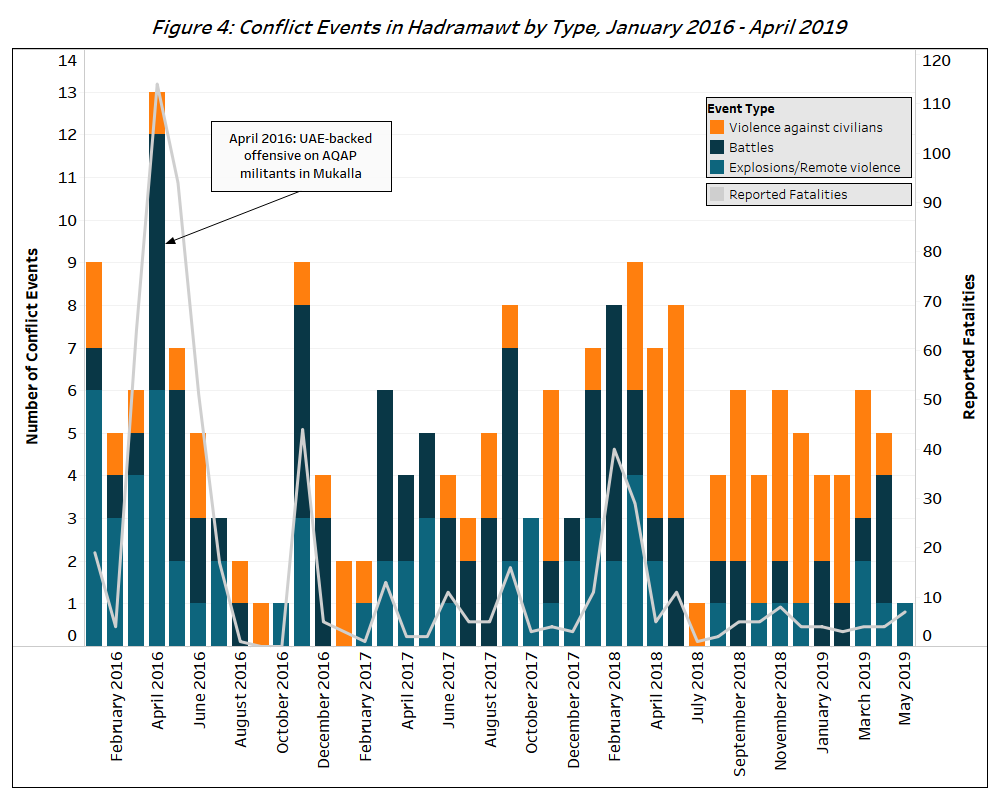

After pushing Houthi and allied forces out of Aden and Marib governorates, Emirati military officials reportedly set their eyes on Mukalla in late 2015. To that effect, they brought back Yemeni military leader Faraj Al-Bahsani from his 20 year-exile in Saudi Arabia and Egypt, and placed him as commander of the 2nd Military District in November 2015, to oversee, alongside Emirati officials, the training of the Hadrami Elite Forces. A total of around 12,000 tribal fighters and other locals from the governorate were mobilised, and successfully recaptured Mukalla in just a few days, with air and ground support from Emirati and US forces (The Atlantic, 22 September 2018). According to some sources, the coalition dislodged AQAP with minimal fighting, sparking controversy over the possibility of a negotiated arrangement between the UAE and the militants, although this is vehemently denied by Abu Dhabi (Associated Press, 6 August 2018). The battle for Mukalla marked the highest peak of violence in Hadramawt since 2016, as depicted in Figure 4 below.

After that, Mukalla has turned from AQAP’s stronghold in southern Yemen to the central hub of the UAE-backed counter-terrorism campaign across the region. According to Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies research fellow Hossam Radman, “popular opposition to AQAP had existed, but was awaiting the shift in the balance of power to act” (Radman, 16 April 2019).

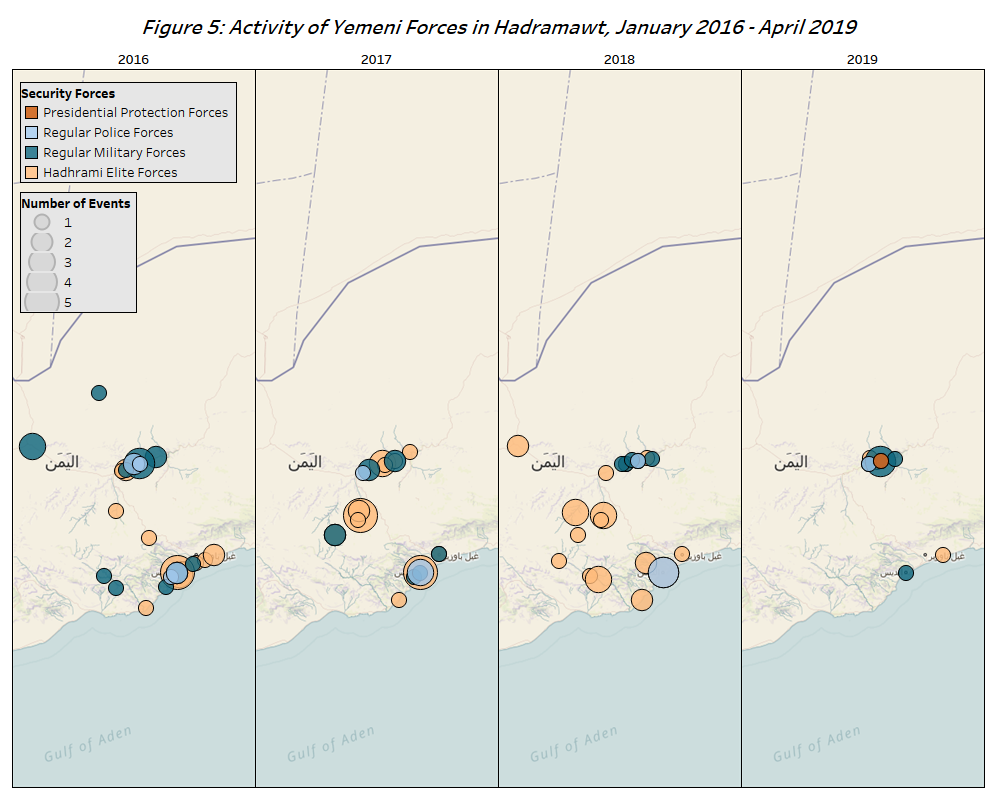

Data collated by ACLED, however, do not reveal a marked decline in AQAP’s activity across Hadramawt until the second half of 2018. This can be explained by two factors. First, AQAP has largely relocated from coastal Hadramawt to its upper regions after they were ousted from Mukalla; second, the counter-terrorism campaigns spearheaded by the Hadrami Elite Forces sparked off a new round of AQAP’s attacks in return. The Hadrami Elite Forces, which might amount to as many as 30,000 fighters according to some Emirati estimates (The National, 11 September 2018), have since largely replaced regular forces in the coastal areas of Hadramawt, moving from their initial counter-terror task to becoming the region’s main security provider. Figure 5 below shows that they have gradually extended their areas of operation from the coastal to the inner regions of Hadramawt, fueling tensions within the governorate.

While Hadramawt has always had one of the strongest sub-national identities, two sub-regional realities have also historically existed within the governorate. The conflict and the involvement of foreign powers have led to the deepening entrenchment of these two realities, increasingly competing on both military and political levels (Ardemagni, 22 April 2019). Coastal Hadramawt is de facto ruled by the STC, although its governor, Faraj Al-Bahsani, has not broken ties with the Hadi government. Similarly, the Hadrami Elite Forces are one of the armed wings of the STC, although they officially fall under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Interior in the internationally-recognised government (UN Panel of Experts, 26 January 2018). In Mukalla, the headquarters of the 2nd Military District, headed by Al-Bahsani, can be found alongside an Emirati military base.

In the north, Hadramawt Valley and the upper desert areas are under the influence of a mix of pro-unity forces, of which the loyalties “remain a matter of debate”; they are mostly split between the old networks of late President Ali Abdullah Saleh, and Islah-affiliated networks of current President Hadi and Vice President Ali Mohsin (Salisbury, 27 March 2018). Hadramawt Valley is centred in the city of Sayun, which houses the headquarters of the 1st Military District commanded by Muhammad Saleh Taymus, believed to be aligned with Al-Islah and close to Vice President Ali Mohsin. A number of Saudi soldiers are also believed to be stationed in northern Hadramawt.

The rivalry between the two Military Districts is likely to have had a direct impact on the security of Hadramis. The data collated by ACLED indeed show that although Hadramawt exhibits low levels of violence in comparison to most governorates in Yemen, it is the fourth governorate where civilians are most likely to be the direct target of violence. The high number of violence against civilians events and its increase since 2018 can be seen in Figure 4 above.

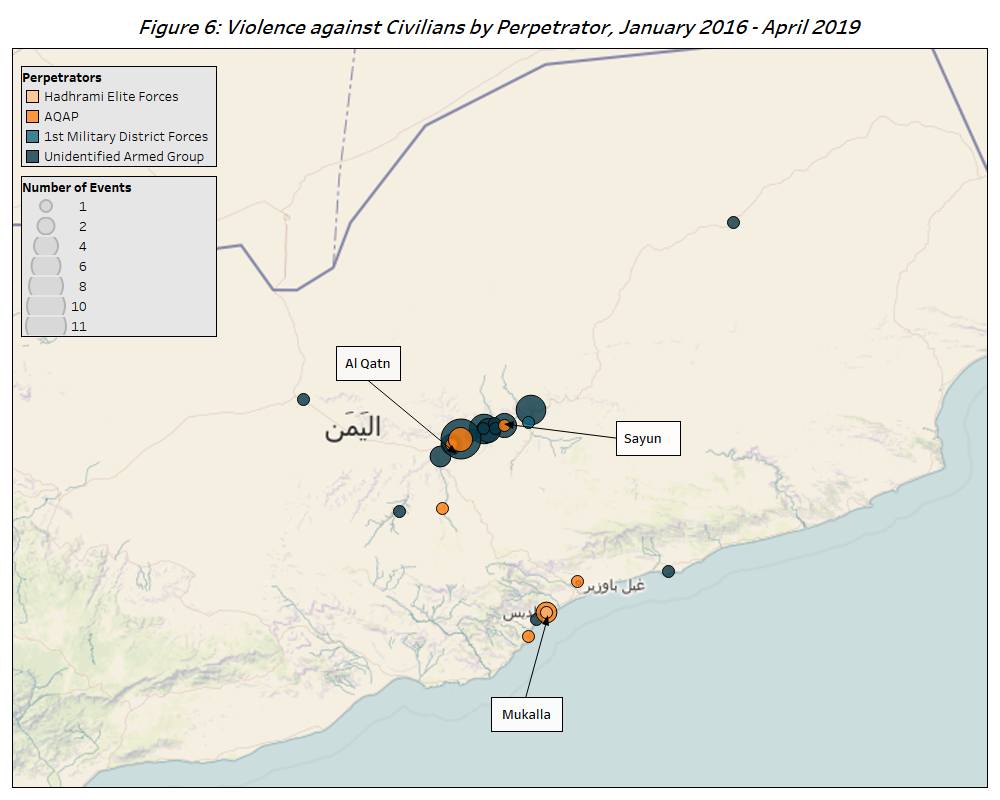

Typically targeting government and security officials as well as tribal and religious figures, these events have been perpetuated by unidentified armed groups in three cases out of four since 2016. Although this is probably the result of a security vacuum created by the lack of collaboration between the two rival security providers of the governorate, Hadramis have often blamed the Mohsin-aligned units for the precarious security situation (The National, 26 July 2018). As can be seen from Figure 6 below, more than 80% of these events indeed take place in Hadramawt Valley. Some of them, however, could also be part of a UAE-backed campaign of targeted assassinations against Islah-affiliated individuals across southern Yemen (Twitter, 23 April 2018; BuzzFeed, 16 October 2018).

The competition between coastal Hadramawt and the valley also plays out in the political arena. In the first half of 2019, Hadramawt housed parliamentary sessions of rival legislatures. On 16-17 February, the STC held the second session of its Southern National Assembly in Mukalla, during which it denounced the “corrupt government” of President Hadi and its attempts at disturbing “the security, stability and social peace in the south” (Southern Transitional Council, 18 February 2019). Just two months later, on 13-16 April, the legislature of the internationally-recognised government, the House of Representatives, held its first meeting since the beginning of the conflict in Sayun (Al-Arabiya, 13 April 2019).

While part of a wider battle for legislative legitimacy between the Hadi and Houthi governments, this meeting exposed the deep fractures running in Hadramawt. Reports emerged of a number of STC leaders arrested by forces of the 1st Military District, while Hadi-loyal Presidential Protection Forces reportedly opened fire on protesters demonstrating against the parliamentary meeting (Southern Transitional Council, 12 April 2019; Al-Omanaa, 13 April 2019; Nokhbat Hadramout, 13 April 2019). On the day of the session, the government complex was also attacked by unidentified gunmen (Al-Janoob Al-Youm, 13 April, 2019).

This latest escalation of tensions can partly be attributed to the increasing impatience of the secessionist faction with the presence of pro-unity forces in Hadramawt Valley. As a number of soldiers from the 1st Military District are from northern governorates, they are in fact considered by some Hadramis as an occupation force in southern Yemen (Al-Masdar, 5 March 2019). During the second session of the Southern National Assembly, parliamentarians suggested the empowerment of Hadrami Elite Forces in Hadramawt Valley and desert (Southern Transitional Council, 18 February 2019).

So far, it seems like Hadramawt’s governor, Faraj Al-Bahsani, has managed to keep tensions from escalating into a wider conflict by bridging divisions within the governorate and remaining relatively neutral. This situation, however, only appears sustainable as long as Al-Bahsani and other figures with influence across both coastal and inner Hadramawt continue to hold sufficient sway over sub-regional actors. As the STC and Hadrami Elite Forces become increasingly emboldened by UAE support, they could eventually attempt to overtake Hadramawt Valley from 1st Military District forces. Such a move would likely trigger a deployment of Islah-affiliated fighters from northern governorates, and fighting along the north-south divide could be reignited.