Midterm legislative elections occur on May 13th in the Philippines, with millions of Filipinos eligible to vote for new lawmakers across the country. But is President Duterte’s hold on power at stake? Probably not. Elections in competitive authoritarian states are primarily a means of consolidating power, done through both managing domestic political elites as well as ensuring mass public support. In the Philippines, violence against politicians has been on the rise. Intimidation, meanwhile, ensures mass public support through the continued “War on Drugs”.

In competitive authoritarian systems, holding elections, the results of elections, and control of who participates are paramount concerns for the regime. Elections play a powerful role in increasing the bargaining power of the ruling party and the dictator. All understand elections as an intra-elite management exercise, rather than a public choice or democratic pursuit; it is the “most important device for the distribution of rents and promotions to important groups with the [politically connected and party structures]” (Blaydes, 2008). For elites, it increases relative power compared to the leader, and offers an opportunity to ‘recalibrate’ their positions by showing how much support they have. For the leaders, elections are an information gathering exercise, and one that leads to strategies to counter new elite factions (Haber, 2006). In practice, it is a loyalty test. Elections can provide considerable information about public support and elite leverage at the local level: citizens actively support the regime if they expect it to last and to continue distributing privileges (Kricheli, 2009) and expect to be punished if they defect (Diaz-Cayeros & Magaloni, 2001). So, the benefits of elections in an authoritarian system are clear: winning is often assured, so in addition to information and reassessments of elite leverage, the exercise also co-opts new members when they deliver votes and areas of support.

If polls prove true, then the Senate positions up for election in the Philippines will go almost exclusively to Duterte’s supporters and allies, as will the races for the 238 congressional seats elected by district and the thousands of local government races (The Diplomat, 29 April 2019). More important is that the Duterte regime has a surplus of candidates, meaning that there will be a number of pro-Duterte candidates who will end up outside of the winning circle (The Diplomat, 29 April 2019).

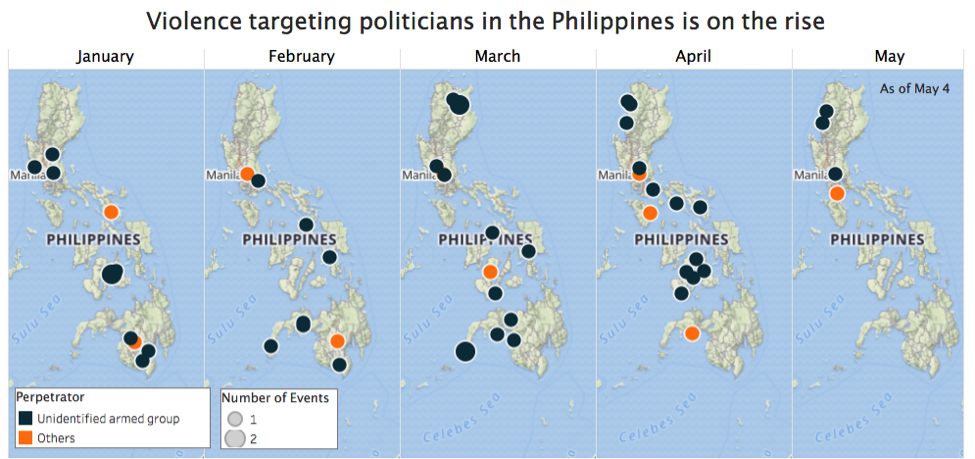

The result is an environment where everyone is out for themselves — competing against both those from opposition parties, but also with others ‘on your side’ for one of a limited number of positions. This could be fueling, at least in part, the rise in violence against politicians across the Philippines. Since the start of the year, the number of events targeting politicians, their associates, and their families has been on the rise across the country (see figures below). Almost all of these events are carried out by unidentified agents under the cloak of anonymity; many of the targets are politicians at the ‘barangay’ or municipal levels of government (New Mandala, 5 March 2019).

Duterte will need to ensure that the elites elected to fill the coveted seats remain loyal. In the immediate future, this will ensure that he can push through his policies and legislation — such as his previous attempts to shift the country to a more federal form of government (Council on Foreign Relations, 24 July 2018), or to grant himself “sweeping powers that could let him rule indefinitely” (South China Morning Post, 9 July 2018). In the longer term, as 2022 and the next presidential election approaches, it can pave the way for a loyal successor. As of now, the Philippine constitution does not allow for Duterte to run for president again — though that need not mean the Philippines will not see a ‘President Duterte’ again, with many suggesting that his daughter may succeed him (Economist, 9 May 2019).

As such, Duterte must reassert his power relative to his senior elites if he is to keep a firm grip on his party. There will be pro-Duterte candidates who are left out of the winning circle during these midterm elections. As has been the case historically, there is a risk of them turning to the opposition (The Diplomat, 29 April 2019). It is hence crucial for Duterte to make the cost of defection high. Unity within the one-party regime is deeply intertwined with the party’s capacity to mobilize the masses (Geddes, 2006, 2008; Magaloni, 2006), as the ‘display’ of support from enormous majorities helps in reasserting its power and makes the cost of the party defecting even higher. Given the regime’s very credible indication that opposition will be publicly identified and targeted, the ‘mass support’ for Duterte is not surprising. This support of enormous majorities would make defection by the party come at an enormous — if not insurmountable — cost.

Mass support of Duterte is high — and whether this support comes as a result of intimidation or true approval can be difficult to discern. The “War on Drugs” is a thinly-veiled state terror campaign, supposedly aimed at “the neutralization of illegal drug personalities nationwide” (Rappler, 22 November 2017) — though in practice, the campaign has resulted in the deaths of thousands of Filipinos, largely the urban poor (Human Rights Watch, 2019), with opposition (Manila Bulletin, 26 January 2019) and journalists regularly caught in the crosshairs. There is credible evidence that the government is using the War on Drugs to kill, detain, or threaten opposition — further politicizing the deadly anti-drug campaign (ACLED, 2018). While it has yet to be conclusively proven that the government is using the watch list to justify the assassination of rival politicians, the “War on Drugs” has been cited as the basis for the arrest of opposition politicians.

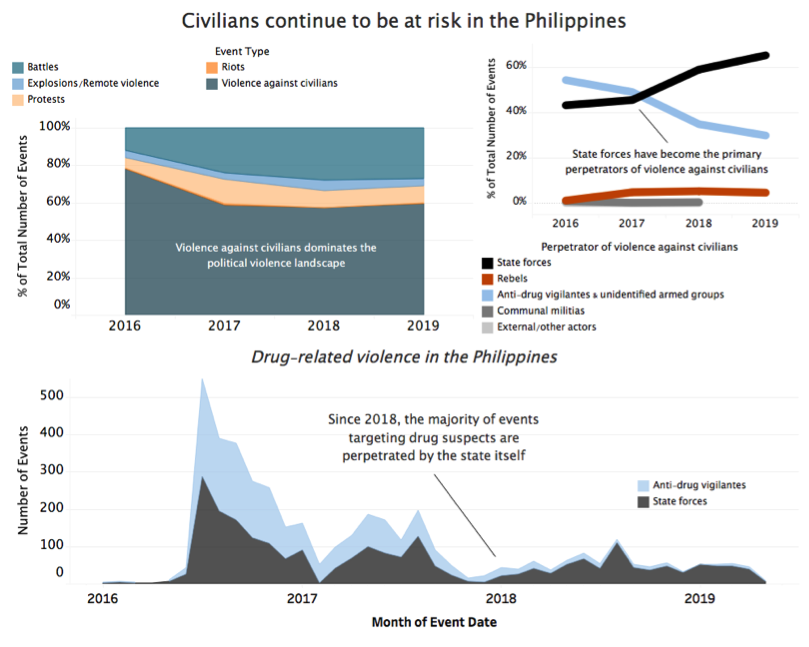

Year after year since Duterte took office, ACLED data point to how violence against civilians has dominated the country’s political violence landscape (see figure below). Over half (if not much more) of political violence in the Philippines each year since 2016 has consisted of violence against civilians. 2019 thus far has continued on the same track. Despite the promise of a less bloody and controversial campaign with the launch of Oplan TokHang 2 in January 2018 (the name of the new phase of the Drug War campaign) (Philippine News Agency, 29 January 2018), last year was the first in which state forces became the primary perpetrators of violence against civilians (see figure below). In years prior, it is likely that much of the violence carried out was indirectly linked to the state (Rappler, 4 October 2018); with Oplan TokHang 2, a majority of events targeting civilians are being perpetrated by the state itself (ACLED, 18 October 2018) (see figure below). The rise of state violence targeting civilians continues in 2019 with nearly two-thirds of all violence against civilians, as of early May, occurring at the hands of the authorities. The Philippine National Police (PNP) is responsible for numerous executions (Human Rights Watch, 2019), and is accused of planting guns and evidence next to drug suspects they have killed (Reuters, 18 April 2017). President Duterte has personally urged the public to seek out and kill suspected drug addicts (The Guardian, 30 June 2016). In a country where you can effectively register “an unlimited number of firearms” (CNN, 5 July 2018), anti-drug vigilantes are not only emboldened, but enabled, to target suspects. Many vigilantes are suspected of having indirect links to the state (Rappler, 4 October 2018). The fact that drug violence perpetrated by these ‘vigilantes’ follows nearly simultaneous cycles as state activity suggests the activity is likely linked (ACLED, 18 October 2018). Many of those targeted by both the state as well as ‘vigilantes’ are named suspects on the President’s ‘watch list’, which contains “anywhere from 600,000 to more than a million suspects” (New York Times, 10 January 2017).

With the support of the masses ensured in no small part thanks to intimidation, and domestic political elites trying to prove their loyalty by taking out any and all competition, it seems the impending midterm elections in the Philippines will be primarily a means for Duterte to consolidate his power as he moves into the latter half of his presidency.