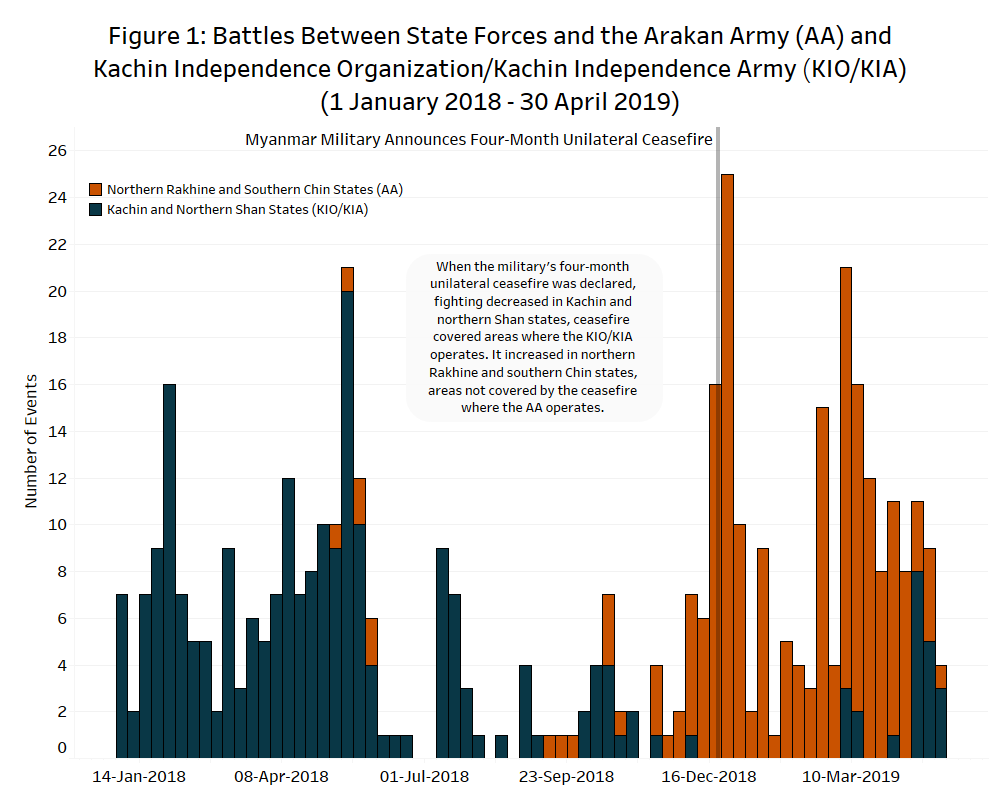

When Myanmar’s military declared a four-month unilateral ceasefire covering the northern and eastern parts of the country on 21 December 2018, its goal was not to cease hostilities, but to narrow the focus of its campaign against the many ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) operating across Myanmar. The geographic scope of the ceasefire meant that while the military’s engagement in ceasefire-covered areas (Kachin and Shan states) decreased significantly, its engagement elsewhere – especially in northern Rakhine and southern Chin states – surged dramatically (see Figure 1). During this time, the military focused resources on weakening one EAO in particular, the Arakan Army (AA), an ethnic Rakhine armed group attempting to establish a base in Rakhine state. However, the AA’s alliance with more powerful EAOs based in ceasefire-covered areas has prevented the military from isolating its conflict with the AA from other conflicts around the country. This inter-EAO alliance has frustrated the Myanmar military’s preferred divide-and-rule approach to engagement with EAOs. Despite the military’s extension of the unilateral ceasefire for another two months, the prospects for peace on the military’s terms remain unlikely.

Conflicting Proposals for Peace

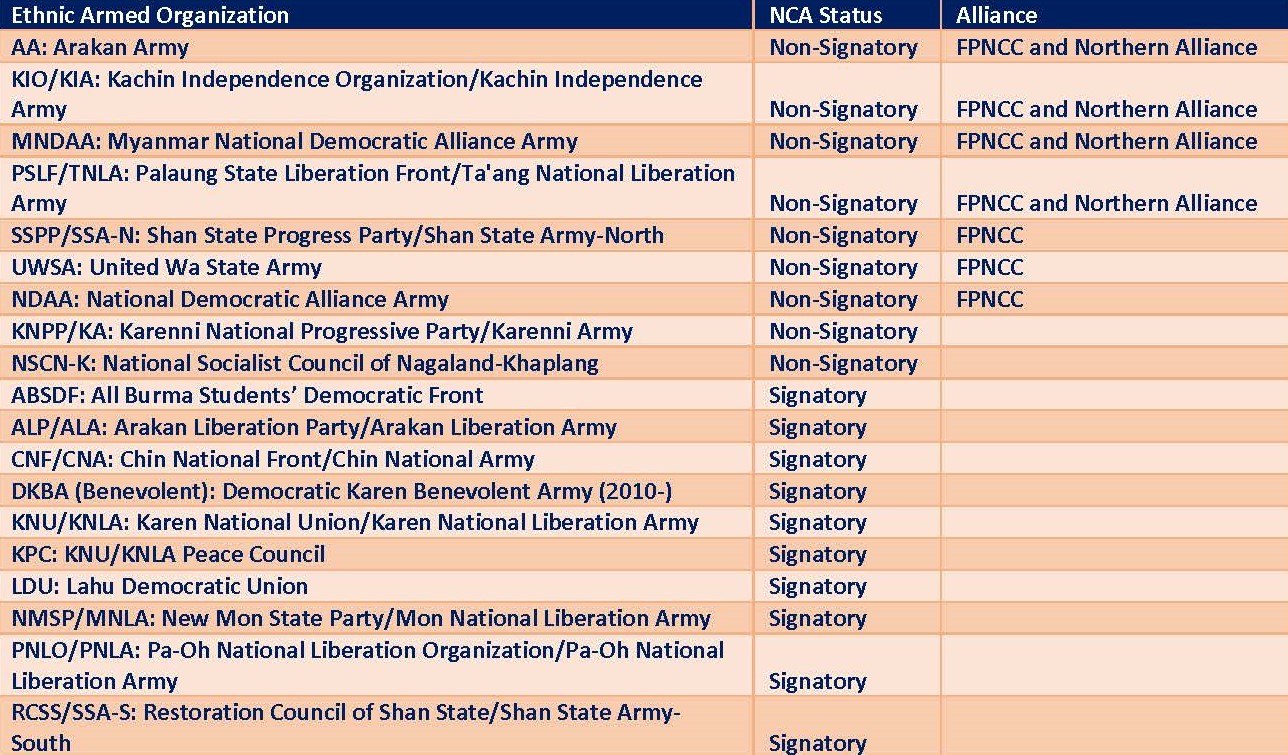

The current approach of the Myanmar military to achieving peace in the country rests on its insistence that all EAOs sign the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) before further formal negotiations can be held — an approach out of alignment with the EAOs currently fighting the military. After 2010, during the rule of the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), the military drafted the NCA, an agreement upholding six principles which the military deemed vital to peace, including adherence to the military-drafted 2008 constitution (Myanmar Times, 2 April 2015). The NCA was signed by eight groups in 2015; two more groups signed the agreement in early 2018. While many expected a different approach to peace when the National League for Democracy (NLD) came to power in 2016, the NLD has instead continued the military’s approach of pressing EAOs to sign the NCA.

The EAOs currently fighting against the military have refused to sign the NCA and instead formed the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee (FPNCC)[1] in 2017. Led by the United Wa State Army (UWSA), the largest EAO in the country, and with China’s backing, the FPNCC has gradually gained influence over discussions of peace in the country (United States Institute for Peace, 29 April 2019). The FPNCC has put forth alternative principles for negotiations that it expects to be considered before the member organizations would agree to sign the NCA (The Irrawaddy, 25 April 2019).

There is a fundamental disagreement between the military and the FPNCC groups regarding the order of steps in the process towards peace. The military expects EAOs to lay down their arms and agree to the NCA, while the FPNCC wants to discuss matters of ethnic equality and self-determination first (Asia Times, 17 April 2019). The misalignment of these two approaches to peace is likely to ensure future conflict, regardless of any ceasefire announced. The current strength of the FPNCC alliance means the military can not continue to push EAOs to sign the NCA and expect peace; progress towards peace would require the military to first address the concerns raised by the allied EAOs.

Alliances between the EAOs also explain why the military’s attempts to silo its conflicts with individual groups has failed during the ceasefire. Some members of the FPNCC, particularly the four groups that comprise the Northern Alliance[2], have indicated they would fight alongside the AA in Rakhine state if needed (The Irrawaddy, 19 March 2019), despite their own areas of operation being covered by the ceasefire. The Northern Alliance put out a statement when the ceasefire was announced calling for Rakhine state to be included (The Irrawaddy, 28 December 2018). It indicated that ongoing fighting there would threaten peace talks and possibly lead to renewed fighting in ceasefire covered areas, demonstrating the strength of the alliance in countering the military’s disparate treatment of EAOs. Thus, as long as the alliance holds, the military will not be able to isolate ethnic armed groups or to contain conflict in the country to a specific geographical location (see Figure 2).

Disorder During the Ceasefire

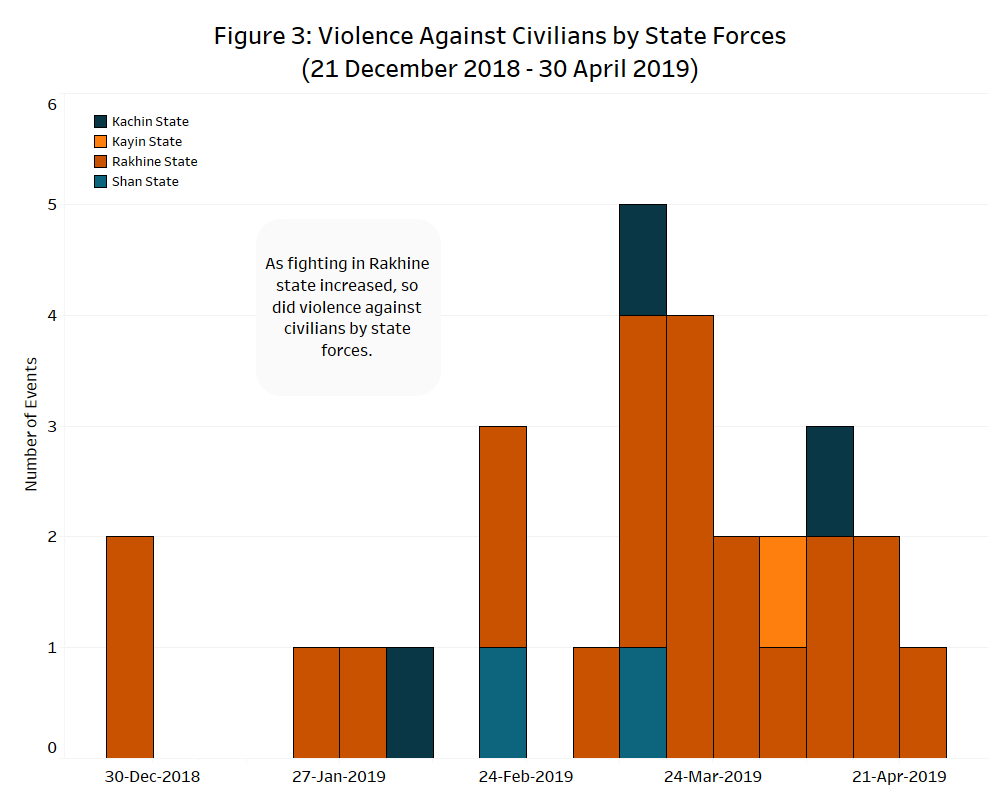

While the unilateral ceasefire was intended to allow the military to target a single group while limiting conflict in other parts of the country, a review of developments during the past four months shows three notable consequences of the ceasefire. Firstly, violence against civilians by state forces increased significantly in Rakhine state as the military targeted villagers perceived as supporting the AA; this targeting of civilians led the AA’s allies to denounce the military’s campaign in Rakhine state. Secondly, the military carried out operations in the Sagaing region in exchange for India preventing the AA from operating within its borders, thus opening another locus of conflict in the country. Finally, while attention was concentrated in Rakhine state, conflict between rival ethnic Shan groups, one a NCA signatory and one a FPNCC member, intensified in Shan state, reflecting to an extent the impact of the military’s peace plan on inter-ethnic unity. These three developments demonstrate the military’s inability to isolate and limit the multiple conflicts in the country.

The military’s focus on the AA during the ceasefire did not just take the form of battles against the group. Given the level of popular support for the AA in Rakhine state (International Crisis Group, 24 January 2019), the military has used this fact as a pretext for violence against civilians. While EAOs have also engaged in violence against civilians, state forces are responsible for most such events (see Figure 3). Both Rakhine and Rohingya communities have been affected by the recent fighting in Rakhine state. In early April, at least six Rohingya villagers were reportedly killed in an aerial attack by the military. More recently, six Rakhine villagers were reportedly shot dead while in military custody. In both cases, the victims were accused of working with the AA (The Irrawaddy, 7 May 2019). The targeting of civilians was the impetus for other Northern Alliance groups to warn the military they would join the fighting in Rakhine state as noted previously: an example of how the military’s tactics have failed to successfully isolate EAOs from each other’s support.

The military’s focus on the AA has also had regional implications. A direct consequence of the fighting in Rakhine state has been the increased activity on the Myanmar-India border (Firstpost, 9 May 2019). In exchange for preventing the AA from operating out of India, the Myanmar military has cracked down on rebel groups from northeast India that have links to the Naga rebels in the Sagaing region along the border with India (Mizzima, 16 March 2019). During the ceasefire, the National Socialist Council of Nagaland-Khaplang (NSCN-K) headquarters in the Sagaing region was taken over by the military and several of the group’s leaders were arrested. They were charged with having contact with unlawful organizations due to their support of various northeast India rebel groups, including the United Liberation Front of Assam-Independent (ULFA-I) (The Irrawaddy, 12 April 2019). While the NSCN-K has not signed the NCA, they do have a bilateral ceasefire with the military. However, the military’s operations in the Sagaing region mean that in trying to contain the AA in Rakhine state, the military has worsened its relations with another EAO, leading to increased conflict in yet another part of the country.

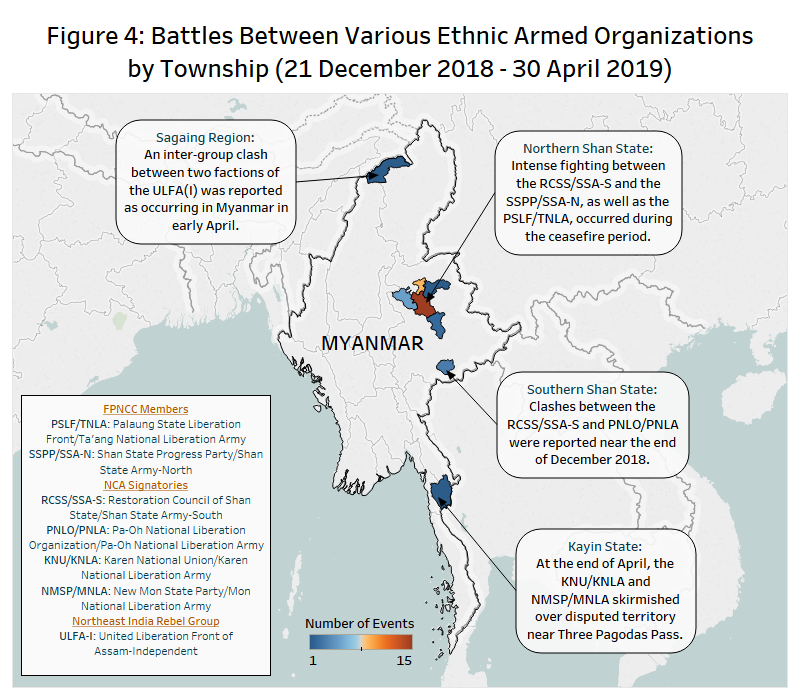

While the ceasefire led to a decrease in military engagement in Kachin and Shan states, conflict in the region did not entirely cease. While much of the conflict in Myanmar is between the military and various EAOs, ongoing territorial disputes between EAOs themselves have been a source of disorder during the four-month ceasefire period as well, particularly in Shan state (see Figure 4). Two ethnic Shan groups, the Restoration Council of Shan State/Shan State Army-South (RCSS/SSA-S) and the SSPP/SSA-N, have fought during this period with much of the fighting taking place in Hsipaw township. The RCSS/SSA-S is a signatory to the NCA while the SSPP/SSA-N is a member of the FPNCC. The SSPP/SSA-N and the PSLF/TNLA, an ethnic Palaung/Ta’ang armed group and member of the FPNCC which has also frequently clashed with the RCSS/SSA-S, have accused the RCSS/SSA-S of using its status as a NCA signatory as cover to expand north (The Irrawaddy, 29 March 2019).

While the conflict between these three groups could be seen as a proxy war (Asia Times, 16 August 2018), the RCSS/SSA-S has denied receiving assistance from the military and the relationship between the RCSS/SSA-S and the military has recently soured with tensions leading to occasional clashes (Radio Free Asia, 28 December 2018). At the end of April, both sides withdrew their troops after talks aimed at promoting unity among ethnic Shan; subsequently battles have declined (Shan Herald Agency for News, 26 April 2019). Yet, the commitment to ending the conflict between the two Shan groups does not extend to the PSLF/TNLA, thus ensuring the likelihood of future conflict in the region regardless of the current military ceasefires.

Prospects for Peace

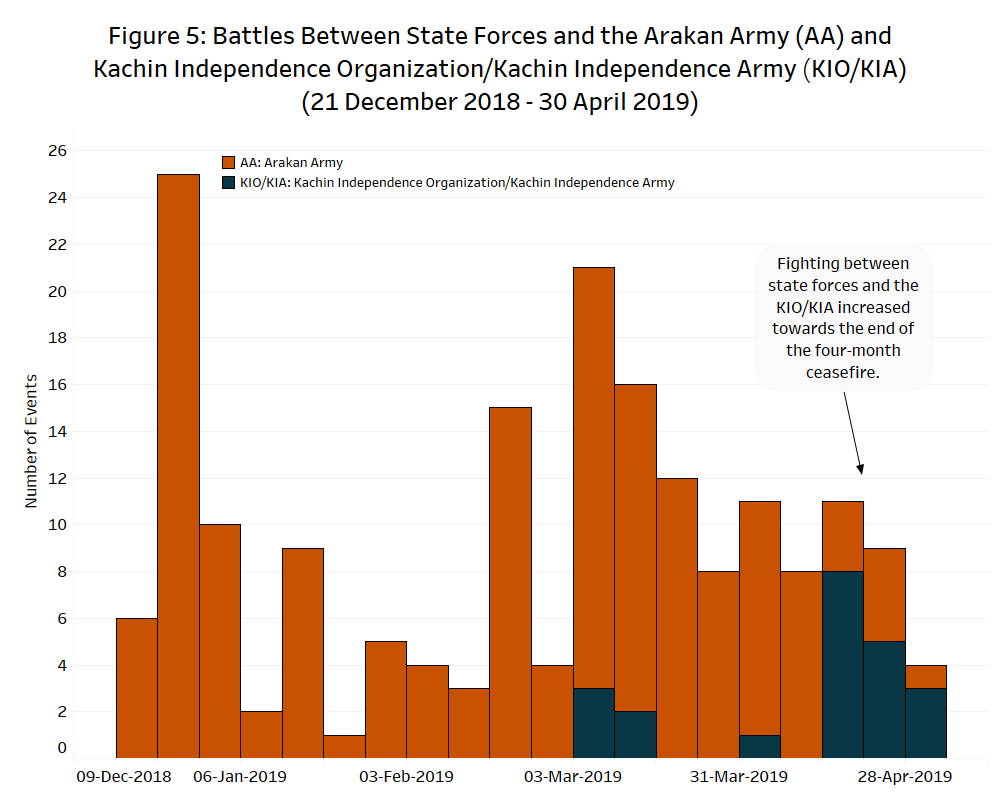

Near the end of April, fighting between the KIO/KIA and the military began to increase in northern Shan state (see Figure 5). Despite the fighting, the military and the Northern Alliance met for talks in Muse on 30 April with other FPNCC members present as observers. After the meeting, the military’s unilateral ceasefire was extended another two months; the ceasefire still excludes Rakhine state (The Irrawaddy, 1 May 2019).

With the extension of the ceasefire, the military has maintained its position that the goal of additional talks during the coming two months is to persuade the alliance groups to sign the NCA (Frontier Myanmar, 1 May 2019). As noted, this approach has not been effective and has been thwarted by the alliance of EAOs insisting on resolving certain issues, namely those of ethnic equality and self-determination, before signing the NCA. While the military has used the ceasefire to concentrate its forces in Rakhine state, the alliance between the AA and other EAOs means the military has been unable to isolate and contain conflict in the country to a single geographic region. Assuming the alliance between the majority of EAOs fighting the military continues to hold, the military will have to contend with their concerns if they aim for peace. Thus, the military’s continued insistence that the NCA is the only acceptable pathway to peace is likely to lead to fighting not only in Rakhine state, but also potentially to renewed fighting in areas covered by the ceasefire in Kachin and northern Shan state.

Appendix 1: Ethnic Armed Organizations in Myanmar

[1] The FPNCC is a political alliance comprised of seven EAOs including the United Wa State Army (UWSA), Kachin Independence Organization/Kachin Independence Army (KIO/KIA), Arakan Army (AA), Palaung State Liberation Front/Ta’ang National Liberation Army (PSLF/TNLA), Shan State Progress Party/Shan State Army-North (SSPP/SSA-N), Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) and National Democratic Alliance Army (NDAA) (see Appendix 1).

[2] The Northern Alliance includes four members of the FPNCC: the Kachin Independence Organization/Kachin Independence Army (KIO/KIA), Arakan Army (AA), Palaung State Liberation Front/Ta’ang National Liberation Army (PSLF/TNLA) and Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA). The KIO/KIA has trained and supported the other three groups which have never signed bilateral ceasefires with the military. The Northern Alliance has recently held meetings with the government peace team with the other members of the FPNCC present as observers.

© 2019 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). All rights reserved.