In Yemen, nearly five years of conflict have contributed to an extreme fragmentation of central power and authority and have often eroded local political orders. Local structures of authority have emerged, along with a plethora of para-state agents and militias at the behest of local elites and international patrons. According to the UN Panel of Experts, despite the disappearance of central authority, “Yemen, as a State, has all but ceased to exist,” replaced by distinct statelets fighting against each other (UN Panel of Experts, 26 January 2018).

This is the second report of a three-part analysis series exploring the fragmentation of state authority in southern Yemen, where a secessionist body – the Southern Transitional Council (STC) – has established itself, not without contestation, as the “legitimate representative” of the southern people (Southern Transitional Council, 7 December 2018). Since its emergence in 2017, the STC has evolved into a state-like entity with an executive body (the Leadership Council), a legislature (the Southern National Assembly), and armed forces, although the latter are under the virtual command structure of the Interior Ministry in the internationally-recognised government of President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi. Investigating conflict dynamics in seven southern governorates, these reports seek to highlight how southern Yemen is all but a monolithic unit, reflecting the divided loyalties and aspirations of its political communities.

This second report focuses on the Arabian Sea island of Socotra and the easternmost region of Mahrah. Previously forming the Mahrah Sultanate of Ghaydah and Socotra, they hold a special place in Yemeni dynamics in that they are the only two governorates that have not been directly affected by the violence of the current conflict. They have, however, been impacted by conflict-related tensions, which are primarily the result of interventionist policies from Saudi-led coalition states, upsetting otherwise peaceful tribal orders.

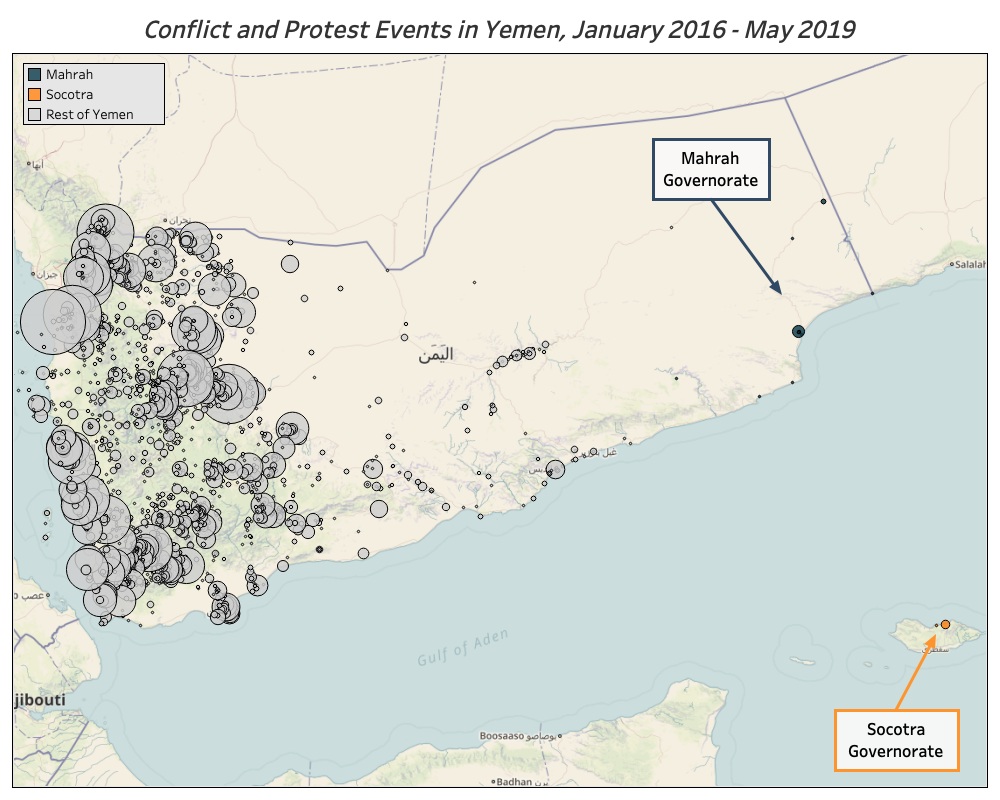

Unlike the rest of Yemen, which has been directly impacted by the violence of the attempted Houthi takeover and the subsequent Saudi-led coalition intervention, these two isolated governorates have remained far from the frontlines since 2014. Yet, at times, they have made international headlines as a result of foreign interventionism and the subsequent local responses. In the first international reporting from Socotra after the war, British newspaper The Independent argued in May 2018 that “Socotra is finally dragged into Yemen’s civil war,” a week after it had reported that the United Arab Emirates (UAE) had “annexed this sovereign piece of Yemen” (The Independent, 2 May 2018). The data collated by ACLED show that the vast majority of conflict and protest events in both Socotra and Mahrah are directly linked to Saudi Arabia and the UAE, as intensified foreign activity in these two governorates has seemingly led to a deteriorating security environment.

Socotra

If the UAE possesses centuries-old ties with Socotra (Baron, 22 March 2019), it significantly increased its presence on the island in November 2015, when it offered relief aid through the Emirates Red Crescent and the Khalifa Foundation after the passage of two cyclones over the island in one week (BBC, 9 November 2015). Since then, Emirati presence has remained high, gaining popularity among local residents through a mix of both hard and soft power. This included the establishment of a military base and the concomitant building of new schools, roads, and hospitals. Some report that their presence “has become a part of everyday life” (The Independent, 2 May 2018). Although the data collated by ACLED record the first protest denouncing Emirati presence on the island in October 2017, interrogations about Abu Dhabi’s wider motives started to arise in late 2016, with some Yemenis referring to a foreign “occupation” of Socotra (The National, 9 January 2017). On 9 April 2018, a second protest was recorded, calling out the occupation of UAE forces and demanding their departure from the island (Voice Yemen, 10 April 2018).

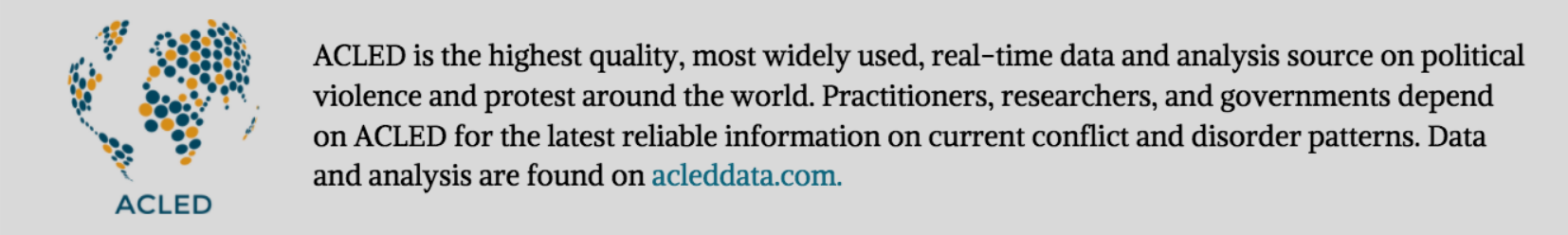

Figure 1 below shows that this event foreshadowed what was perhaps the worst diplomatic crisis between the internationally-recognised government of President Hadi and the UAE. On 2 May 2018, more than a hundred Emirati troops arrived on Socotra and took control of its sea and airports, deploying tanks and other armoured vehicles, while then-Yemen’s Prime Minister Ahmed bin Daghr was on a rare visit to the island (Yemen Monitor, 3 May 2018; Yemen Press, 3 May 2018). After accusing Abu Dhabi of occupying Socotra in “an act of aggression”, bin Daghr and ten of his ministers were prevented from leaving the island by UAE forces controlling the airport (Al-Jazeera, 4 May 2019).

As shown in Figure 1, this incident sparked the largest wave of protests recorded by ACLED on the island over the January 2016 – May 2019 period[1], with protesters alternately chanting for the UAE to leave Socotra and for continued Emirati presence on the island. The escalation of the crisis was prevented by Saudi Arabia, which, on 13 May, deployed its own forces to the island (Al-Arabiya, 13 May 2018). A few days later, reports emerged of UAE forces leaving Socotra following a deal brokered by Saudi emissaries (Middle East Eye, 18 May 2018). As seen in Figure 1, protest activity subsequently declined and ACLED records no other anti-UAE protest until March 2019. Yet, Emirati forces remained on the island, albeit more discreetly, avoiding similar shows of force.

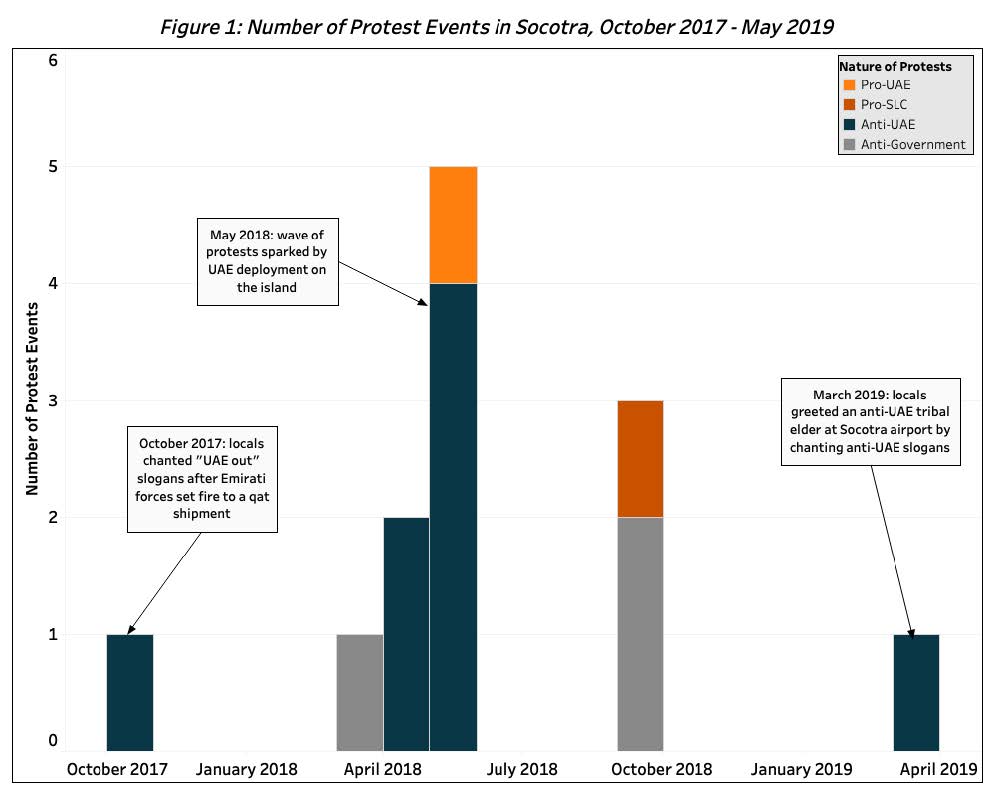

Lying 240km east of the Horn of Africa and 380km south of Yemen, the island of Socotra stands in a strategic passageway of international trade shipping routes, which are at the center of Abu Dhabi’s expansionist plan to become a key maritime power in the Yemen and Horn of Africa region (ACLED, 10 October 2018). In an intertwining of the UAE’s economic and military interests, for instance, reports emerged in April 2019 that an Emirati military base was being built right next to Hawlaf port (Al-Sharq, 1 April 2019; Yemen News Agency, 1 April 2019), which had been rebuilt by Abu Dhabi in March 2018 through the Khalifa Foundation (Arabian Industry, 12 March 2018). The main infrastructures of the island can be seen in Figure 2 below.

In early May 2019, former governor of Socotra and UAE-backed STC member Major General Salim Al-Socotri confirmed the arrival on the island of more than 100 locals who had been trained in Aden by Emirati forces (Al-Ameen Press, 8 May 2019). Reports alleged that these newly-trained fighters arrived aboard a UAE military ship as part of the Security Belt forces, one of the armed wings of the STC, while around 200 others were still undertaking training (Al-Mawqea Post, 8 May 2019).[2] Interestingly, this development, which was officially condemned by the Hadi government, occurred less than ten days after current and Hadi-aligned Socotra governor Ramzi Mahrus declared that he would not allow for the creation of Security Belt-like forces on the island (Al-Mahrah Post, 29 April 2019). If this new episode of tensions has not yet escalated further, the developments in Socotra need to be watched with attention, as continued Emirati engagement in the island and its alleged desire to turn it into a “military outpost-cum-holiday resort” (The Independent, 2 May 2018) have already disrupted its social fabric and could create durable divisions, which, in the longer-term, could turn into political violence.

Mahrah

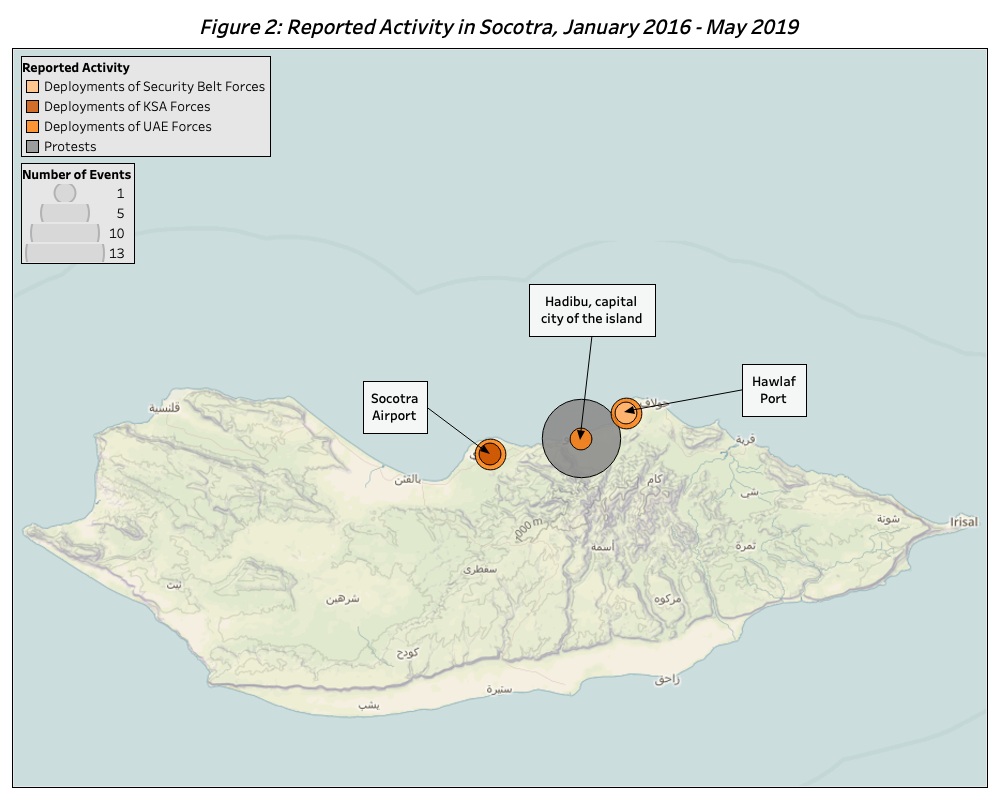

In the mainland governorate of Mahrah, which has traditionally been within Oman’s sphere of influence, a mix of both Emirati and Saudi interventionism seems to be increasingly upsetting the consensus-based tribal governance that has historically kept the region peaceful. In the data collated by ACLED since January 2016, only four conflict and protest events have been recorded in both 2016 and 2017, while 37 events were recorded between January 2018 and May 2019. Out of the 28 recorded protest events, 23 were directly aimed at Saudi-led coalition interference within the governorate. Figure 3 below shows protest events in Mahrah between January 2016 and May 2019.

Abu Dhabi and Riyadh, however, are engaging in Mahrah for different reasons. To Abu Dhabi, Mahrah likely represents the last governorate that has yet to become part of a unified southern Yemen under STC leadership. Although the secessionist body opened headquarters in Mahrah in late 2017 (Southern Transitional Council, 21 December 2017), it faced stronger resistance than in other southern governorates when it attempted to establish its own local security force (Aden Al-Ghad, 28 October 2017). Yet, in early 2019, reports emerged that a force of 4,000 Mahris trained by UAE troops in Hadramawt had set up headquarters in both Mahrah’s capital Al-Ghaydah and neighboring Hawf district, although they allegedly rapidly left Hawf following local tribal protests. The success of Abu Dhabi’s enterprise in Mahrah is unclear; as of late May 2019, ACLED records no activity of these so-called Mahri Elite forces.

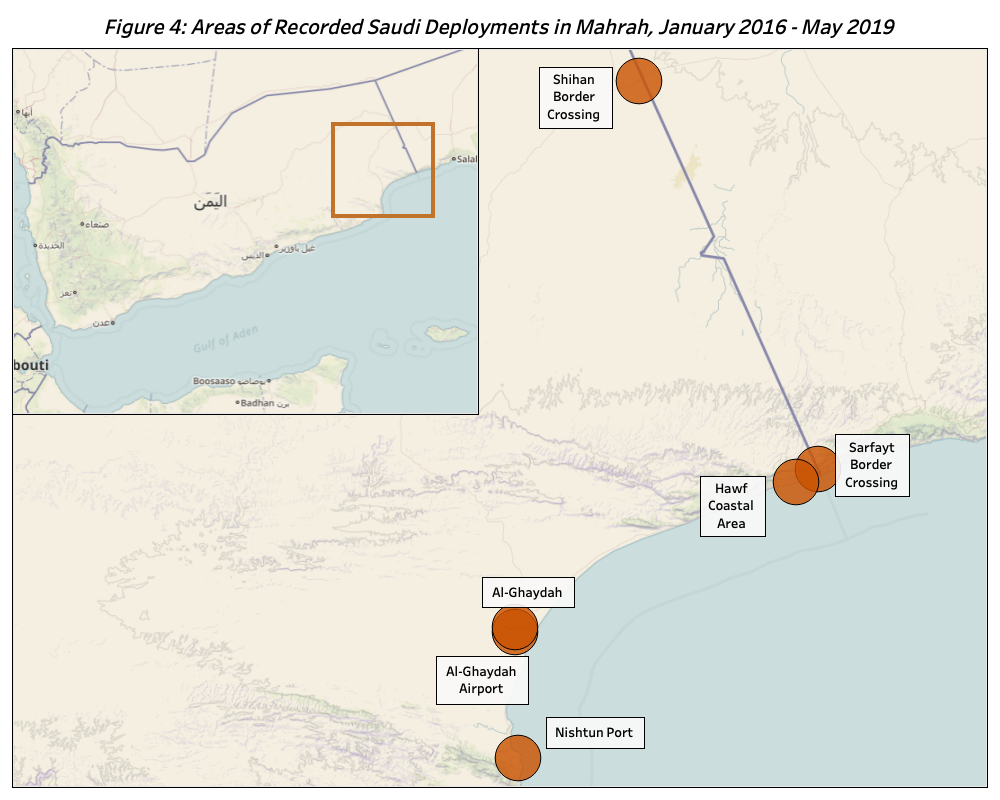

For Riyadh, interfering with local dynamics in Mahrah is seen as an existential necessity, as the governorate has become a smuggling hub that permits the transit of Iranian weapons posing a direct threat to Saudi territorial integrity (Salisbury, 20 December 2017; Salisbury, 27 March 2018). In November 2017, a team of UN experts assessed that ballistic missiles fired by the Houthis into Saudi Arabia most likely entered Yemen along “the land routes from Oman or Ghaydah and Nishtun in Al-Mahrah governorate” (Reuters, 1 December 2017). This has prompted Riyadh to deploy a large number of troops and military equipment to the governorate’s main entry points on several occasions, encroaching on Omani influence in the region while attempting to target smuggling groups (Nagi, 19 October 2018). Figure 4 below shows the various areas where ACLED has recorded the deployment of Saudi forces. In July 2018, one of these deployments led to the outbreak of a Socotra-like crisis, by which a week of protests against the control of Al-Ghaydah’s airport by Saudi troops led to their withdrawal after agreeing to a deal with local authorities (Al-Masirah, 14 July 2018; Aden Al-Ghad, 14 July 2018).

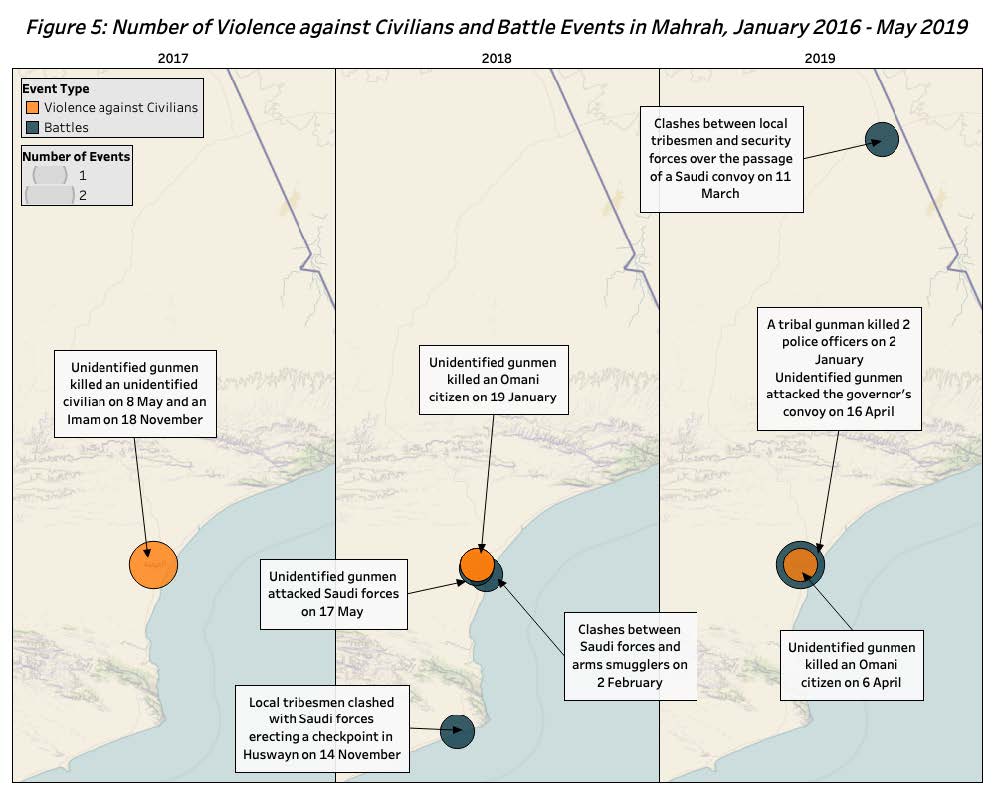

Like the UAE in Socotra, Saudi Arabia has gained popular support among certain local residents by providing aid, through the King Salman Humanitarian Aid and Relief Center and the Saudi Development and Reconstruction Authority, and by attempting to clamp down on smuggling networks (Twitter, 27 December 2017). At the same time, however, it has also been accused of interfering with the local social fabric, for instance by sponsoring the arrival of hundreds of Salafis led by Shaykh Al-Hajuri to build a Salafi school in the coastal town of Qishn, while Mahrah is a traditionally Sufi region (Twitter, 10 January 2018). Controversy also surrounds an alleged Saudi plan to build a pipeline linking oil fields in eastern Saudi Arabia to a new oil terminal in Mahrah, which would allow the Kingdom to export its oil via the Arabian Sea while bypassing the Iranian-controlled Strait of Hormuz (Al-Jazeera, 20 August 2018; Aden Al-Ghad, 29 September 2018). Yet, as of May 2019, it seems that neither Emirati nor Saudi interference has resulted in systemic political violence. Figure 5 below, however, shows that conflict events seem to be increasing amid a deteriorating security environment.

In an exceptionally rare incident, Mahrah’s governor, Rajit Bakrit, was targeted by an assassination attempt on 16 April 2019 (Aden Al-Ghad, 17 April 2019). Out of fear that this would spark a cycle of violence in the governorate, locals soon after staged a protest demanding his resignation. In May 2019, ACLED recorded the first ever Houthi activity in the governorate, as Saudi air defence systems shot down a Houthi-operated reconnaissance drone over Al-Ghaydah (Aden Al-Ghad, 17 May 2019). Although the perspective of sustained Houthi activity in Mahrah is illusory, this incident attests that the Saudi-led coalition military build-up is seriously impacting the security situation.

As the evolution of Emirati and Saudi engagement in Mahrah is uncertain – they could exploit differences within the governorate’s military establishment (Salisbury, 27 March 2018) like they have done in Hadramawt – Oman’s position will likely be determinant. While Mahrah’s stability is of the utmost importance to Muscat, acting like a buffer zone between the Sultanate and the Houthi conflict, it will most likely attempt to act as a mediator between the various regional and local interests currently being shaped in the governorate, although there have also been reports that it has funded protests against Saudi-led coalition presence (Nagi, 19 October 2018). In the yet unlikely event that Abu Dhabi and Riyadh impede too much on Muscat’s own interests, however, Yemen’s eastern neighbor could also decide to adopt a more aggressive approach in its engagement with Mahrah. In this context, it is noteworthy that Shaykh Abdullah bin Issa Al-Afrar, son of the former Sultan and Chairman of the General Council of the Sons of Mahrah and Socotra, a body which seeks self-rule for the two governorates, was given Omani citizenship in July 2017 (Aden Al-Ghad, 30 July 2017).

______________

[1] For data vizualization reasons, Figure 1 starts from October 2017. Between January 2016 and October 2017, ACLED only recorded one event in Socotra: a protest against the federal plan to unify Socotra, Mahrah, Hadramawt, and Shabwah governorates into the “Greater Hadramawt” region.

[2] During the May 2018 Socotra crisis, the STC showed support to the UAE and not the Yemeni government (Southern Transitional Council, 7 May 2018).