With the inclusion of data covering Yemen and Saudi Arabia from 2015 into the ACLED dataset, ACLED is now able to track the escalation of the conflict since the start of the Saudi-led coalition intervention in March 2015. What is important to bear in mind, however, is that the conflict already started several months earlier, with the Houthi takeover of the capital Sanaa in September 2014.[1]

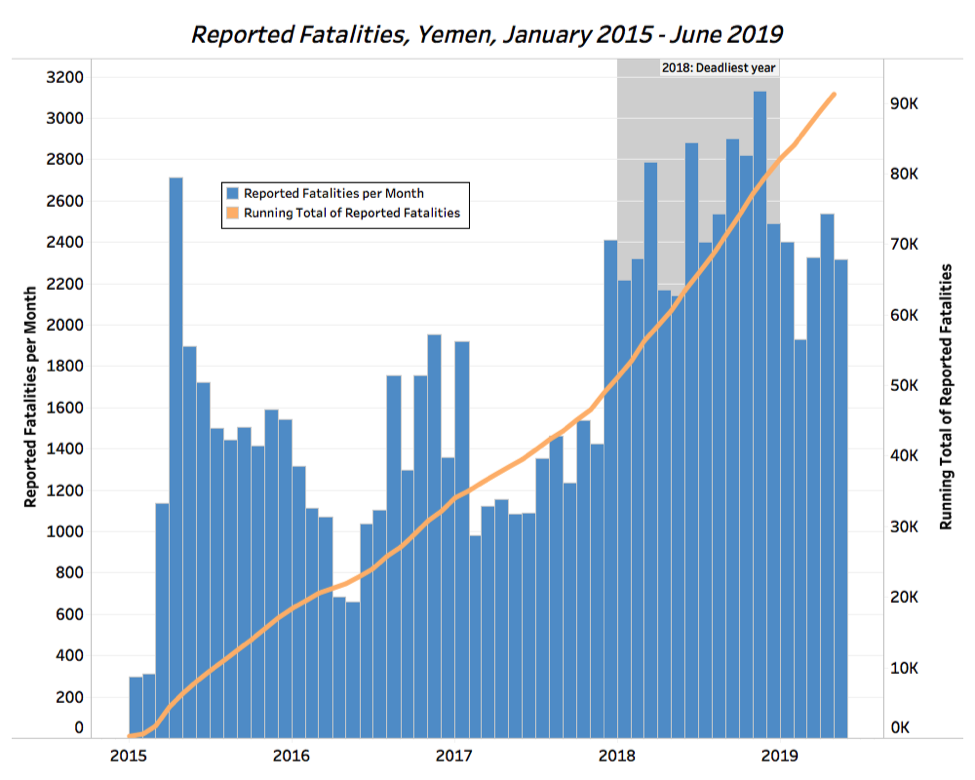

1. Total Reported Fatalities

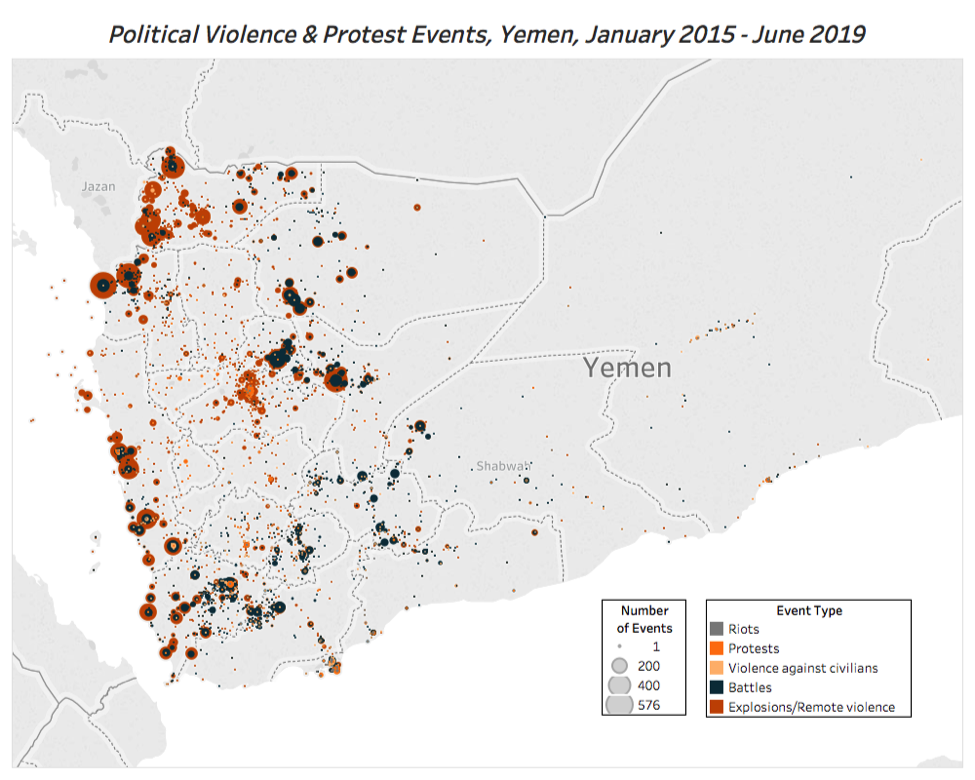

The deadliest year of the war in Yemen has been 2018, especially between April and December 2018, as can be seen in the graph below. This lethality in armed confrontations during that time can be traced back to the deadly Hodeidah offensive by UAE-supported Yemeni forces to reconquer the port of Hodeidah from the Houthi Movement. The Stockholm Ceasefire Agreement contributed to a partial decrease in reported fatalities, although heavy clashes continued in other fronts in Ad Dali, Hajjah, and Taiz during the decrease in heavy battles on the Hodeidah front (ACLED, 20 March 2019).

Throughout the war, reported fatalities (including civilian fatalities) in Taiz governorate were continuously among the highest in the ACLED data, going back to a 4-year long siege laid by Houthi forces. A plethora of different militias with the goal of fighting the Houthis emerged in the third-largest city of Yemen and its surroundings, sometimes with conflicting agendas (ACLED, 7 December 2018). The staggering death toll of 18,419 reported fatalities, among them 2,282 civilian fatalities, makes Taiz governorate by far the most violent governorate throughout the last four years.

Second to Taiz governorate, are Hodeidah governorate — where reported fatalities in the year 2018 increased drastically (due to the Emirate-supported offensive by Yemeni groups), totalling almost 10,000 since 2015 — and Al Jawf governorate — for which ACLED tracks a similar number of reported fatalities. Indiscriminate attacks against civilians and the nature of city combat, however, makes the conflict for civilians in Hodeidah governorate five times as lethal as in Al Jawf, with respectively 1,828 relative to 359 civilian fatalities reported.

Other major hotspots of the conflict in Yemen are Sadah governorate, with consistent fighting along the borders with Saudi Arabia; Sanaa governorate, which surrounds the capital Sanaa; Marib governorate; Hajjah governorate; and Al Bayda governorate. All of these governorates have in common that they include or have included active frontlines between Houthi forces and anti-Houthi forces. Reported fatalities in these governorates range between 6,000 and 7,500 since 2015.

Concerning is the recent skyrocketing rise in reported fatalities in Ad Dali governorate, where the year 2019 already accounts for more than half of the 4,000 reported fatalities since 2015.

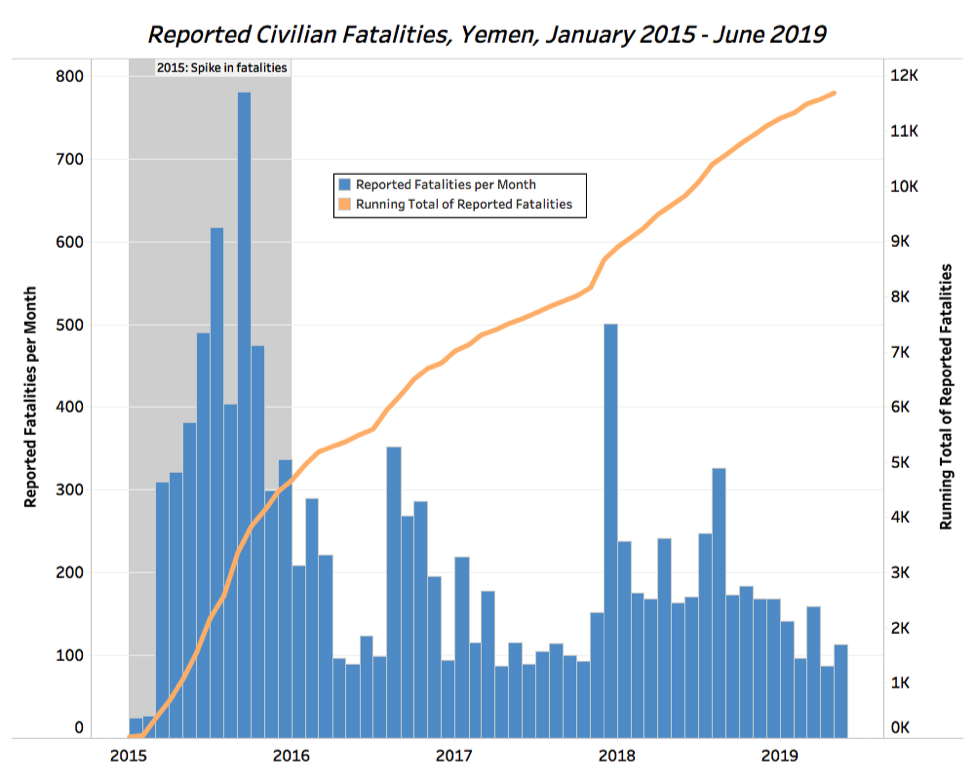

2. Civilian Fatalities

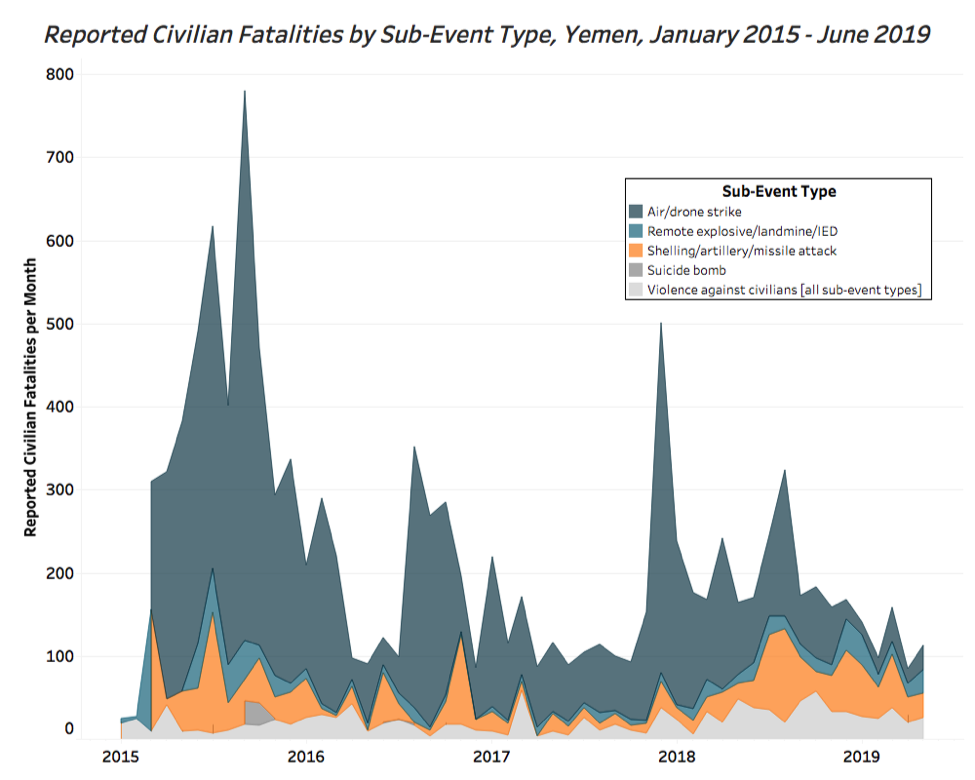

In contrast to the continued high number of fatalities resulting from armed clashes, civilians in 2019 live in less danger of being killed through political violence than they did in 2015. Although the Saudi-led coalition only started on 25 March 2015, the highly indiscriminate targeting of civilians in Yemen by Saudi-led airstrikes during the first months of the intervention made 2015 the most lethal year of the war (as can be seen in the figure below). The reported estimate of 4,468 reported civilian fatalities in 2015 makes 2015 almost doubly as lethal as the second-most lethal year, 2018, with 2,426 reported civilian fatalities. As the graph below exemplifies, reported civilian fatalities spiked in 2015, with only some months — such as August 2016, December 2017 or August 2018 — accounting for a similar elevated number of civilian fatalities per month. In general, however, what the graph shows is that civilians are less and less likely to be killed through incidents directly related to political violence; it is important to remember, however, that civilian fatalities that occur as a result of collateral damage are not depicted here. Additionally, these numbers do not include deaths from the cholera crisis or potential famine-related deaths (The Guardian, 17 April 2019 ; The Guardian, 15 October 2018).

Around 67% of all reported civilian fatalities in Yemen since 2015, resulting from direct targeting, have been caused by Saudi-led coalition airstrikes, making the Saudi-led coalition the actor most responsible for civilian deaths. As the graph below demonstrates through the spikes between 2015-2016 and at the end of 2018, air and drone strikes were especially deadly for civilians in 2015 and during the Hodeidah offensive in 2018. Nonetheless, since November and December 2018, ACLED reports a significant decrease in the number of airstrikes directly targeting civilians in Yemen. This might be explained by the decrease in the number of reported civilian fatalities in Hodeidah due to the Stockholm Agreement, though could also be due to increased international pressure on Saudi Arabia after the Khashoggi affair. The surfacing of the alleged ruthless role that the Kingdom played in the dismemberment of Khashoggi has also shed new light on the role of Saudi Arabia in the crisis in Yemen. Most visibly, the US Congress has brought the Yemen crisis to the forefront through adopting a Yemen resolution, invoking the War Powers Resolution, which was subsequently vetoed by the White House (Washington Post, 13 March 2019 ; Reuters, 2 May 2019).

The number of reported civilian fatalities varies throughout Yemen’s governorates. Living in Hodeidah, Taiz, and Sadah governorates has been extremely lethal for civilians. In each governorate more than 2,000 civilians have been killed since 2015 — combined making up more than half of all civilian fatalities reported in Yemen since 2015. More than 75% of the direct civilian fatalities in these governorates are caused by airstrikes from the Saudi-led coalition. This percentage is a bit higher than the 67% of civilian fatalities which are caused by airstrikes in the whole of Yemen.

3. The Increasing Danger of Landmines

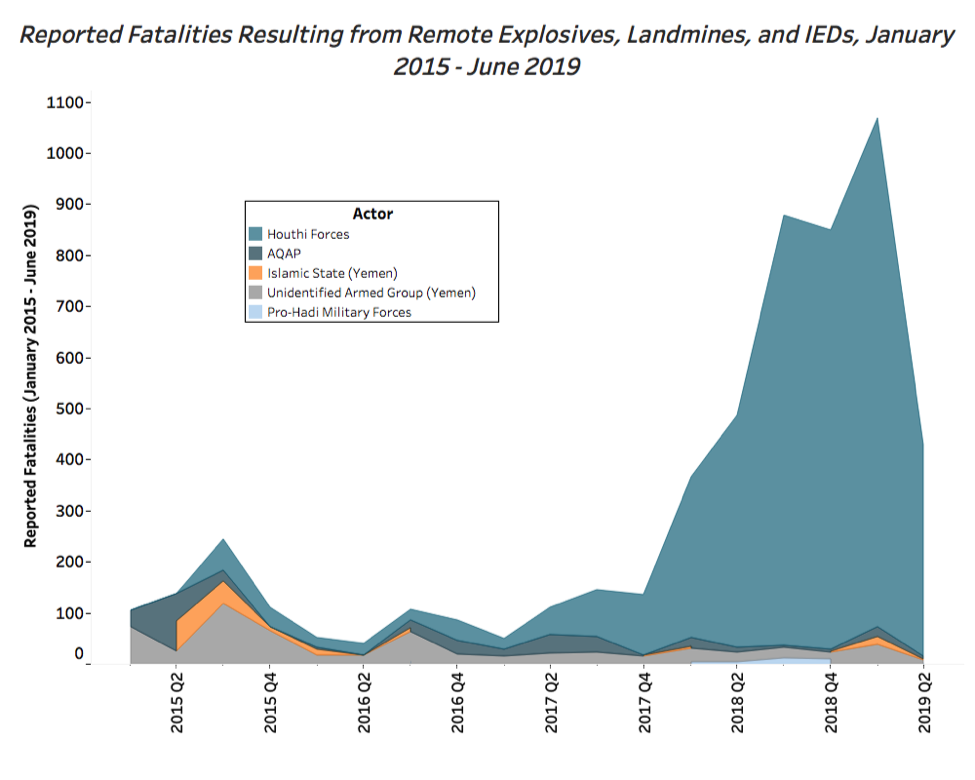

Since 2015, ACLED records nearly 5,500 fatalities caused by remote explosives, IEDs, and landmines in Yemen;[2] more than 80% of these have occurred since 2017. In general, the responsibility for the rise in explosions and remote violence events lies primarily with Houthi forces. According to some estimates, they have laid more than a million land and sea mines since the war started, turning Yemen into “the most-mined nation since World War II” (Associated Press, 24 December 2018).

The continued increased danger of landmines killing combatants as well as civilians can, since 2018, mainly be traced back to a planned strategy by Houthi forces to mine Southern districts of Hodeidah province (ACLED, 30 January 2019). This strategy seems to replicate a pattern observed in Aden in 2015, when Houthi-Saleh forces retreating from the southern port city similarly deployed thousands of anti-personnel and anti-tank landmines to obstruct the movement of troops.

Next to Houthi forces (in teal), almost all other violent incidents by remote explosives were caused by AQAP (in navy) or the Islamic State (in orange) — or unidentified or anonymous armed groups (in gray), due to the difficult task of attributing remote explosives. Pro-Hadi military forces and other pro-government militias (light blue) account for a dwindling number of remote explosive fatalities in Yemen, as can be seen in the figure below.

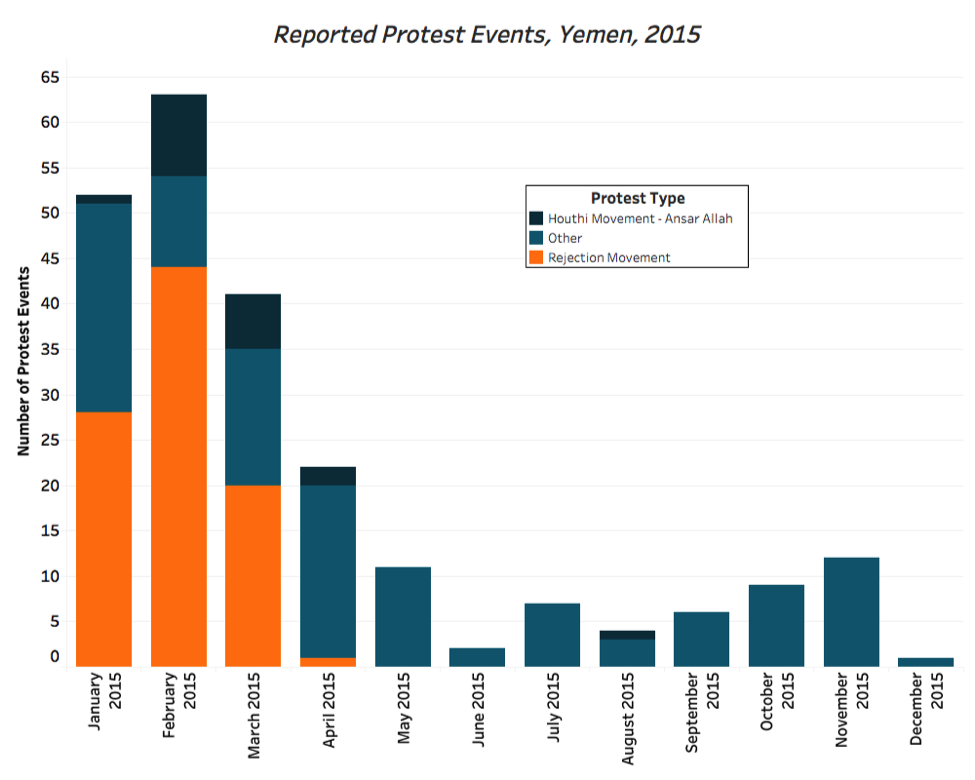

4. Anti-Houthi Protests and the Saudi Intervention

2015 has been one of the years with the strongest resistance to Houthi role. In the first three months Yemenis organised a significant number of protests in Yemen against Houthi rule (‘Rejection Movement’) (in orange) in cities such as Sanaa or Ibb, as can be seen in the figure below. On the other hand, some pro-Houthi protests were being organised by the Houthi Movement itself (in navy). However, with the start of the Saudi-led coalition intervention and the first airstrikes on 25 March 2015, these two types of protests slumped. Yemenis steered their anger away from the authoritarian rule of the Houthi movement towards the ‘more illegitimate’ Saudi-led bombing. A major part of the subsequent protests in 2015 was addressed against the indiscriminate bombing of Yemen by Saudi-led coalition airstrikes. Since then, no official protests against Houthi-rule have been reported. This, however, is not only explained by the extremely lethal first months of Saudi-led coalition bombing, but also by the consolidation of control by Houthi forces over their constituencies.

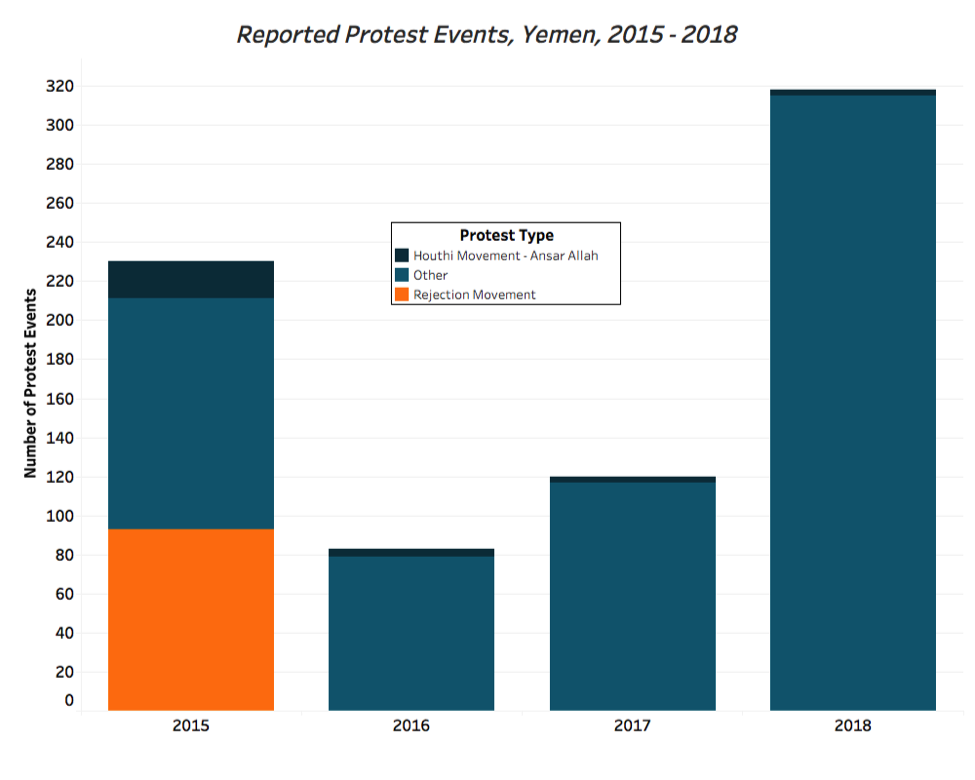

Protest activity subsequently stagnated until 2018 (as seen in the figure below), when Yemen was hit by an exchange-rate crisis and soaring inflation, which brought Yemenis to the streets again. The crisis had been caused by the ongoing fracture of the Yemeni Central Bank, expulsion of Yemeni expat workers from other Gulf countries, and printing of new rial banknotes to pay public servants (Sanaa Center, 16 October 2018). In 2018, protests had a high frequency in the temporary capital of the internationally-recognised government in Aden. ACLED indeed reports a higher number of protest events in 2018 than in 2015.

5. Conclusion

The few snapshots above are only a sample of how these data allow users to look more deeply at trends regarding fatalities, the impact of airstrikes on civilians, the increasing danger of IEDs and landmines, and the trajectory of high-intensity battlefronts such as Taiz or Al Jawf.

ACLED’s extending coverage of Yemen and Saudi Arabia from the present back to 2015 allows policymakers and stakeholders to have a more complete picture of the war in Yemen. These new data capture the entire period of the Saudi-led coalition intervention in Yemen, which started in March 2015 and escalated the war. The detailed information now available can facilitate further granular analysis to shed more light on developments during the war which do not find their way into the spotlight.

__________________

[1] Data for 2014 is not yet part of the ACLED dataset.

[2] All explosives that detonate without a delivery method (e.g. they were planted, buried, set as a booby-trap, etc.) are part of the ACLED sub-event type called “Remote explosive/IED/landmine”. This includes unexploded ordinances (UXO) that did not detonate during past strikes or bombardments, such as cluster munitions, shells, or other types of explosive which may become buried only to detonate later.