After nearly six months of continuous protests, tensions between demonstrators and the Sudanese Transitional Government are mounting. On June 3, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), opened fire on a peaceful sit-in in Khartoum. This event, in which more than 100 people were reportedly killed, followed weeks of gradually increasing levels of RSF activity. Since the protests began on December 19, 2018, the RSF has been responsible for more reported fatalities and more instances of violence against civilians than the military and police combined. Increasing reliance on the RSF to respond to the largely peaceful protests presents a serious threat to civilians in Sudan. The RSF’s history of brutality and impunity in Darfur, as well as current reports of infighting between the RSF and other members of the security sector, suggests that the increase in the group’s activities will drive instability in Sudan.

Introduction to the RSF and Recent RSF Activity

The RSF is a paramilitary force that was established in 2013 under the Sudanese intelligence bureau, the National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) (Sudan Tribune, June 11, 2014). The RSF was fashioned out of Janjaweed militias and was assembled in response to anti-government rebel movements in Darfur (DW, June 9, 2019). The RSF has been accused of a myriad of human rights abuses in Darfur and elsewhere (Human Rights Watch, May 8, 2019). In recent years, the RSF was used as a coup-proofing mechanism for President Omar al-Bashir — who was recently forced out of power because of popular demonstrations against his regime (Al Jazeera, June 5, 2019).

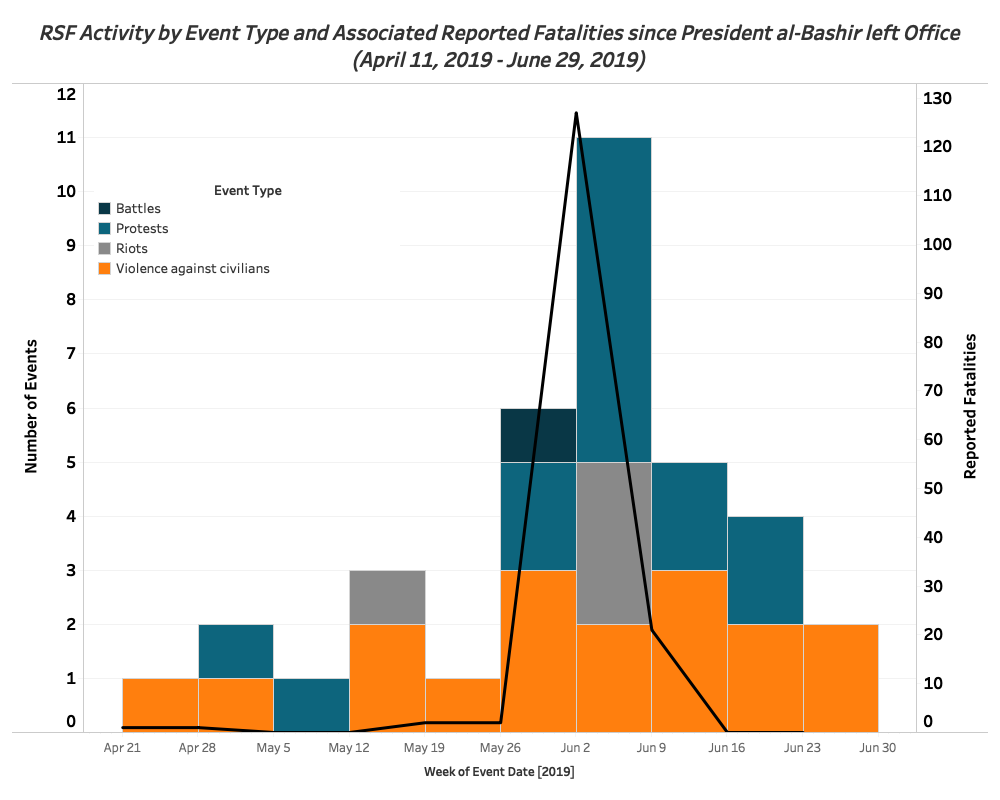

As demonstrated below, RSF activity has been sporadic throughout the demonstration period and their activity surged in mid-May. The timing of this surge, nearly a month after al-Bashir left office, likely relates to the jockeying for influence within the Transitional Military Council (TMC) and the conflict between the civilian demonstrators and the TMC (TimesNowNews, May 20, 2019; France24, May 6, 2019). The RSF’s commander and the deputy head of the Transitional Military Council is Hamdan Dagalo (more frequently referred to as “Hemedti”), who many have speculated is angling for influence in post-Bashir Sudan (The Guardian, May 29, 2019).

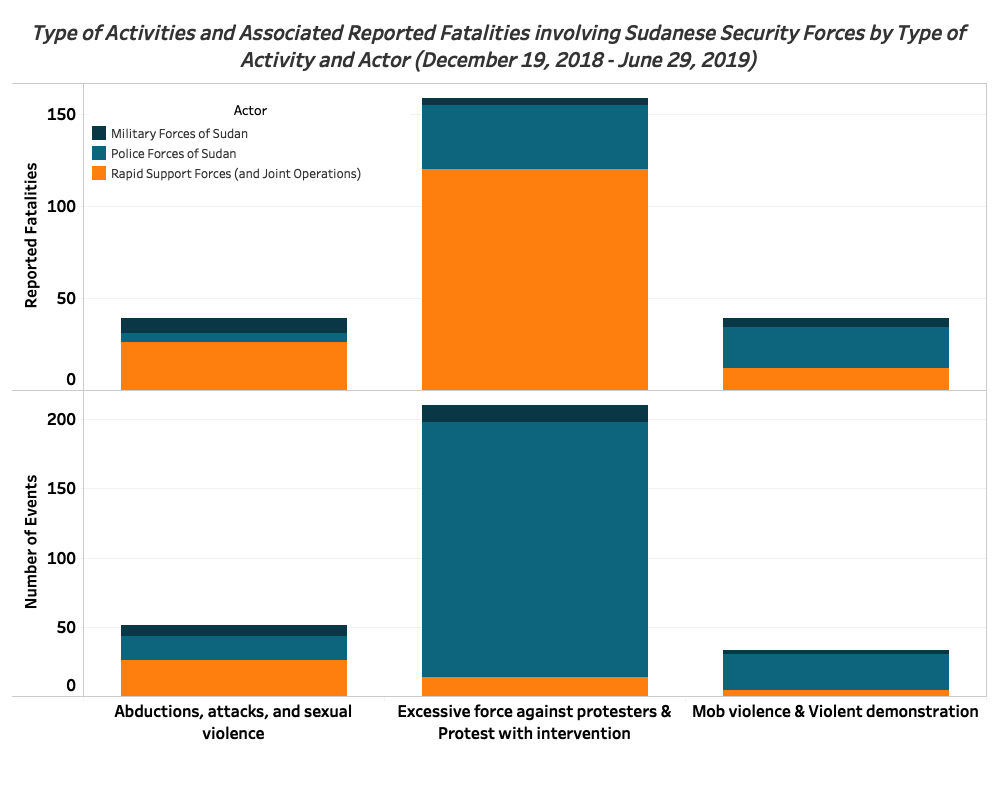

Though the RSF is a part of the Sudanese security sector, it has demonstrated a different pattern of violence than the Sudanese police and military. More than half of the events in which the RSF have been involved since the protest wave began are instances of violence against civilians. This is compared to 25% of events involving the military (not including events in which the RSF and the military act in joint operations, which are included in the tally for the RSF’s activities) and fewer than 10% of events involving the police. Early June’s activity is an example of this difference in lethal tactics. Of the less than 10 recorded instances of the RSF using excessive force against protestors, many are associated with in total 120 reported fatalities. In comparison, in the nearly 50 instances in which the police and military have used excessive force against protesters, 40 fatalities, or fewer than 1 per event, are reported. Notably, the RSF also stands accused of a number of instances of sexual violence; during the June 3 crackdown in Khartoum: at least 70 rapes associated with the RSF are reported.

The Rise of the RSF and the Future of Sudan

Hemedti has refused to take responsibility for the RSF’s activities, attributing the violence to “imposter troops among the Rapid Support Forces” (CityNews, June 20, 2019). Yet, the RSF’s violence against civilians in Khartoum echoes the force’s history in Darfur, where the militia is accused of sexual violence, extralegal killing, and other war crimes (Amnesty International, June 11 2019)

The largely peaceful, civilian-led protests were a significant force behind the removal of President al-Bashir, eventually becoming significant enough to convince the country’s elites to turn against the government. Since al-Bashir’s departure, an elite military council (TMC) has taken control of the government. The TMC and the civilian demonstrators have been unable to come to an agreement about timelines for elections and the proportion of transitional government seats that should be allocated to civilians (AlJazeera, June 26, 2019; Voice of America, May 15, 2019).

Another distressing sign for Sudan’s political trajectory are reports that the RSF is engaging in violence against members of the Sudanese military who show solidarity or sympathy for the demonstrators (DW, June 9, 2019). AfricaConfidential reported that “a security source in Khartoum,” relayed that “when some soldiers heard of the RSF and NISS plans to attack civilians at the sit-in, they were told to stay in the barracks and that no arms would be issued to them” (AfricaConfidential, June 14, 2019). Such directives, after previous weeks in which some members of the armed forces displayed solidarity with demonstrators, alludes to the divisions within the TMC. There have been reports of “arrests, detentions or banishments of dissident junior officers” recently (AfricaConfidential, June 14, 2019). Fragmentation within the Sudanese security sector could escalate into civil conflict.

Thus, the activities of the RSF present a two-fold threat to a post-Bashir Sudan. Firstly, the RSF’s violence against civilians imperils the likelihood of continued peaceful protests and suggests that the calls for a civilian-led government will go unheeded. Secondly, the RSF’s targeting of Sudanese military members could trigger a bloody process of influence-jockeying.

© 2019 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). All rights reserved.