On 11 June 2020, militants believed to be members of the Al Qaeda-affiliated Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) attacked a mixed Ivorian military and gendarmerie post in the border village of Kafolo — the first jihadi militant attack to strike Ivory Coast since the 2016 shootings at the Grand-Bassam resort. While the Kafolo incident marks a rare attack in Ivory Coast, which has otherwise been spared the violence plaguing its northern neighbors, it is not a surprising development for three reasons. First, there was an initial misjudgment by Burkinabe authorities of the threat along the common border. Second, jihadi militants present between Burkina Faso and Ivory Coast have been able to grow and develop their capabilities largely uninhibited. Lastly, a combination of mistrust and poor coordination between the Burkinabe and Ivorian governments has delayed the formulation of an adequate response to the rising militancy.

Beyond an Obsolete Paradigm

In January 2019, ACLED analysis found that the jihadi militant threat in the border region between Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, and Mali had re-emerged after a long hibernation between 2015 and 2018 (for more information, see this ACLED report). Since 2018, when militant activities began in earnest in Burkina Faso, the situation has rapidly deteriorated in the country’s southwest. Armed assaults have been reported against fixed positions and patrols of the police, gendarmerie, and customs. These attacks represent a significant change from the past when violence was largely limited to conventional rural banditry and intercommunal violence over land disputes, chieftaincy successions, and customary rites.

A focus on such outdated patterns of violence appears to have distorted the perspective of Burkinabe authorities. For too long, officials have dismissed attacks in the southwestern regions of Hauts-Bassins, Cascades, and Sud-Ouest as the work of armed bandits, or members the former Blaise Compaoré regime’s dissolved presidential guard (RSP), seeking to undermine the country’s security as part of a “destabilization campaign” (BBC, 2017; VOA Afrique, 2018, Le Monde, 2019). This is an obsolete paradigm. Instead, current developments must be viewed through a more complex prism of jihadism and banditry, a nexus of both forms of violence that could be translated into the “jihadization of banditry.” For instance, groups such as JNIM and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) have proven effective in transforming a range of armed actors — bandits, rebels, militiamen, smugglers, local militants, and poachers — into allied groups and auxiliaries, establishing unity of purpose to subvert state control and facilitate illicit activities.

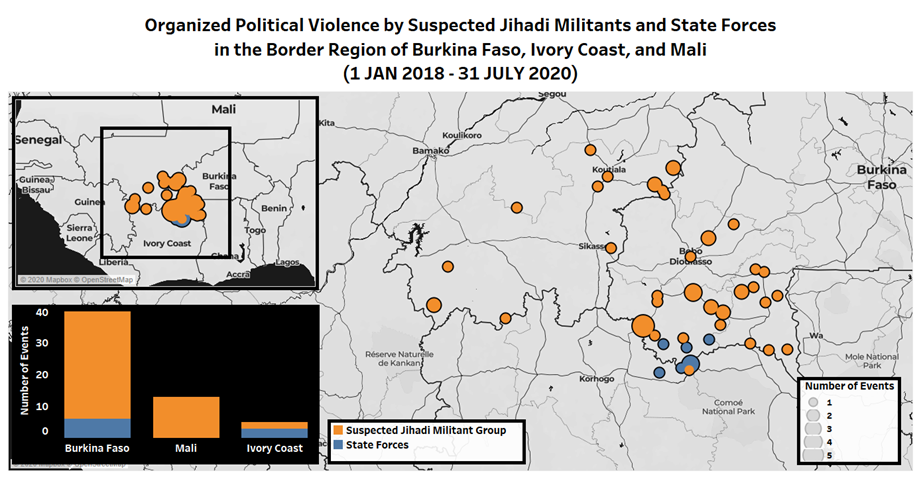

The government’s long-standing denial or misinterpretation of the nature of violence in the southwestern regions may be explained by an unwillingness to admit that the situation was even worse than expected – and to concede the state’s role in perpetuating the crisis. The inadequate diagnosis has delayed the formulation of an effective and timely response to the insurgency, providing a textbook example of how authorities often misjudge threats and exhibit a general disinterest in the periphery, distant from the centers of power. The poor response of Burkinabe authorities consequently enabled the rise of a local katiba (or brigade) in the region. The creeping jihadi militant expansion across the border now threatens the northernmost regions of Ivory Coast. Despite the relatively low intensity of militant activities in the border region, data clearly show that militant actions outmatch those of state forces in Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, and Mali, though Ivorian forces have largely proven more responsive than their Burkinabe and Malian counterparts (see figure below).

The Emergence of a Katiba

JNIM’s constituent groups — the Sahara branch of Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, Al Mourabitoun, and Katiba Macina (Ansar Dine’s contingent in central and southern Mali) — established a presence in the border region between Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, and Mali as early as 2015. While organized political violence was sporadic and the network was presumably dismantled by security forces, remnants of these groups maintained a presence in the area. Katiba Macina, through the influence of its leader, the Fulani preacher Amadou Kouffa, continued to activate and arm mainly local Fulani groups. The jihadi militant network operating across the southwestern regions consists of a mobile cell-based structure with the nucleus found around Alidougou, a hamlet situated on the border between Burkina Faso and Ivory Coast. Alidougou constitutes the “markaz” (“center” in Arabic) or base, part of Katiba Macina’s decentralized chain of command (ICG, 2019).

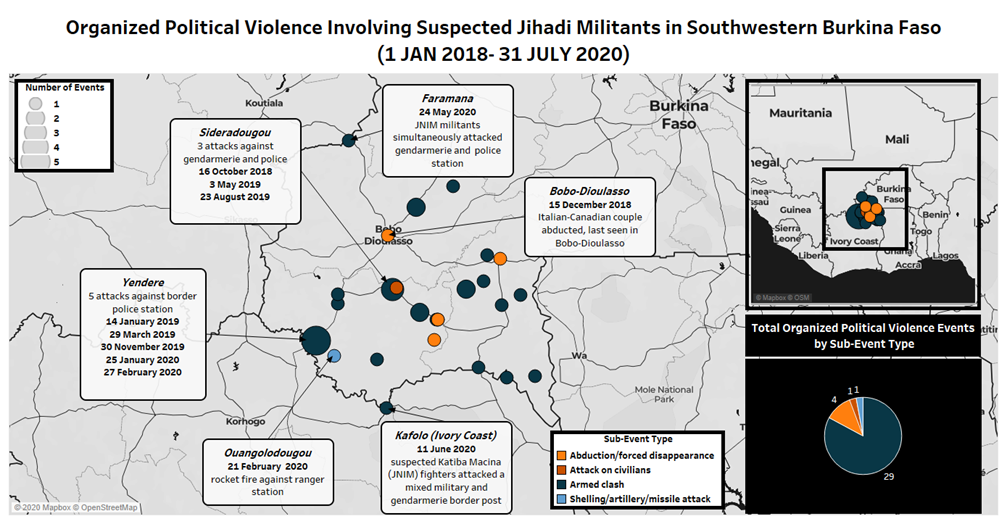

The group’s modi operandi are largely composed of depredation tactics by way of motorcycle-borne armed assaults and ambushes, but also kidnapping operations. Deploying a rudimentary strategy to wear down security infrastructure through overrun attacks and sabotage, combined with harassment tactics to weaken the presence of security forces, the militants have worked to create a significant area of influence (see figure below). Katiba Macina activities near industrial and artisanal mining sites further suggest that the group aspires to become a local security provider, challenging government forces and Dozo militiamen. While the local Katiba Macina branch remains in the early stages of its evolution compared to confederates in other regions and has not overtly articulated any objective of territorial management, multiple reports indicate that it has begun proselytizing their ideology and attempting to regulate communities by prohibiting alcohol consumption and collaboration with security and defense forces across the Cascades region.

From Mistrust to Cooperation

Fearing spillover of jihadi militant violence, the Ivorian government surged 300 troops to the north and launched Operation ‘Frontière étanche’ (“Watertight border”) in July 2019, in order to counter possible attacks and to prevent militants from using Ivorian territory as refuge (Le Monde, 2019). Burkinabe authorities have been slow to respond to the brewing low-intensity insurgency in southwestern Burkina Faso. The effective launch of counter-militancy operations did not start until early October 2019, over a year after the first attacks in the area. This left neighboring Ivory Coast to anxiously watch its northern border. The level of coordination between Ivory Coast and Burkina Faso has been insufficient and undermined by mistrust, delaying the process of pooling resources and forming a united front. Burkinabe forces reportedly conducted two operations, including airstrikes in October 2019 and a sweep operation in January 2020, without informing the Ivorians, causing a minor media imbroglio (LSi Africa, 2020).

In May 2020, the two countries were finally able to come together to confront the common threat by launching a large-scale joint operation, monikered Operation Comoé, on both sides of the border. The counter-militancy operation began on 12 May against fighters believed to be JNIM. Burkinabe and Ivorian military leaders met in the Ivorian border village of Kafolo for a ceremony to conclude the operation on 22 May (Sidwaya, 2020). The joint force dismantled a jihadi militant base near the village of Alidougou, killing eight fighters, arresting 24 suspects in Burkina Faso and 14 in Ivory Coast, and recovering weapons and equipment.This represented its first publicized tactical success (Jeune Afrique, 2020).

Operation Comoé 2020 and the Aftermath

While the two unilateral Burkinabe operations conducted before Operation Comoé proved little more than disruptive to jihadi militant activities at best, the joint Burkinabe-Ivorian operation produced tangible results: the dismantling of the Alidougou base camp and the recovery of significant weapons and logistic materiel. On 28 May, the pro-Al Qaeda propaganda outlet Thabat News Agency published a report on the joint operation saying that it targeted JNIM fighters. The report described Ivorian forces actions as an “overland intervention,” and indirectly threatened Ivory Coast by recalling the 2016 Grand-Bassam shootings.1“Algeria’s and Ivory Coast’s overland intervention in the losing war against Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin [JNIM],” Thabat News Agency, May 28, 2020. Three days after Operation Comoé ended, JNIM fighters simultaneously overran two gendarmerie and police stations in the Burkinabe village of Faramana.2Militants killed two gendarmes in the attack, burned the police station, and seized a vehicle, motorbikes, weapons, and equipment. JNIM claimed responsibility for the Faramana attack in an unofficial video on 26 May, showcasing the arms and equipment seized. On 1 June, JNIM issued an official statement via its propaganda arm Al Zallaga Media Foundation and said that the attack took place “near the common border between Mali, Burkina Faso, and Ivory Coast.” This is likely meant to subtly frame the assault as a response to Operation Comoé even though Faramana is located approximately 200 kilometers from the border with Ivory Coast.

The seriousness of Thabat News Agency’s threat was realized less than three weeks after Operation Comoé, when presumed Katiba Macina militants affiliated with JNIM attacked a mixed military and gendarmerie post in the border village of Kafolo on 11 June, killing 14 Ivorian troops (Koaci, 2020). As militants based in Alidougou have operated in the area — to a great degree unimpeded — only kilometers away from Kafolo, the attack is not entirely unexpected. However, it demonstrates that even in the wake of a large-scale joint operation, militants were able to regroup and launch a devastating mass-casualty attack in just a matter of weeks – a significantly quicker turnaround compared to the drawn out coordination process between Ivorian and Burkinabe authorities.

Still, the attack came as something of a wake-up call for the Ivorian government, which retaliated with airstrikes and soon announced that it had tracked down and arrested Ali Sidibe (also known as “Sofiane”), the alleged “mastermind” of the Kafolo attack (Yeclo, 2020). In response to the attack and persistent insecurity along the country’s northern borders, the government further authorized the creation of an “operational military zone” in the north amid a special cabinet session on 13 July in order to improve border surveillance and prevent militant infiltration (Connection Ivorienne, 2020).

Regional Outlook

ACLED data show that attacks in southwestern Burkina Faso doubled in the first four months of the year compared to the same period in 2019. There were eight attacks in 2020 and four in 2019. The Ivory Coast-Burkina Faso border region remains at risk, although a calm has reigned since the attacks on Faramana and Kafolo. However, this relative tranquillity was outbalanced by a corresponding increase in attacks on the Malian side of the borders.3Three attacks took place in NGoutjina (Sikasso), Massigui (Koulikoro), and Kimparana (Segou), all in Mali’s south and near the borders with Burkina Faso. Militant groups in the Ivory Coast-Burkina Faso border area have suffered significant setbacks, including the dismantling of logistic infrastructure and the arrests of suspected cell members and key operatives. In this context, it is likely that militant groups operating in the region will keep a lower profile in the face of a more united front from Burkinabe and Ivorian forces, now on the alert and pooling assets to confront the shared threat along their common borders.

© 2020 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). All rights reserved.