Conflict Watchlist 2025 | The Great Lakes region

Lasting peace remains elusive between armed groups with international ties

Rwanda, Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda, and Burundi

Posted: 12 December 2024

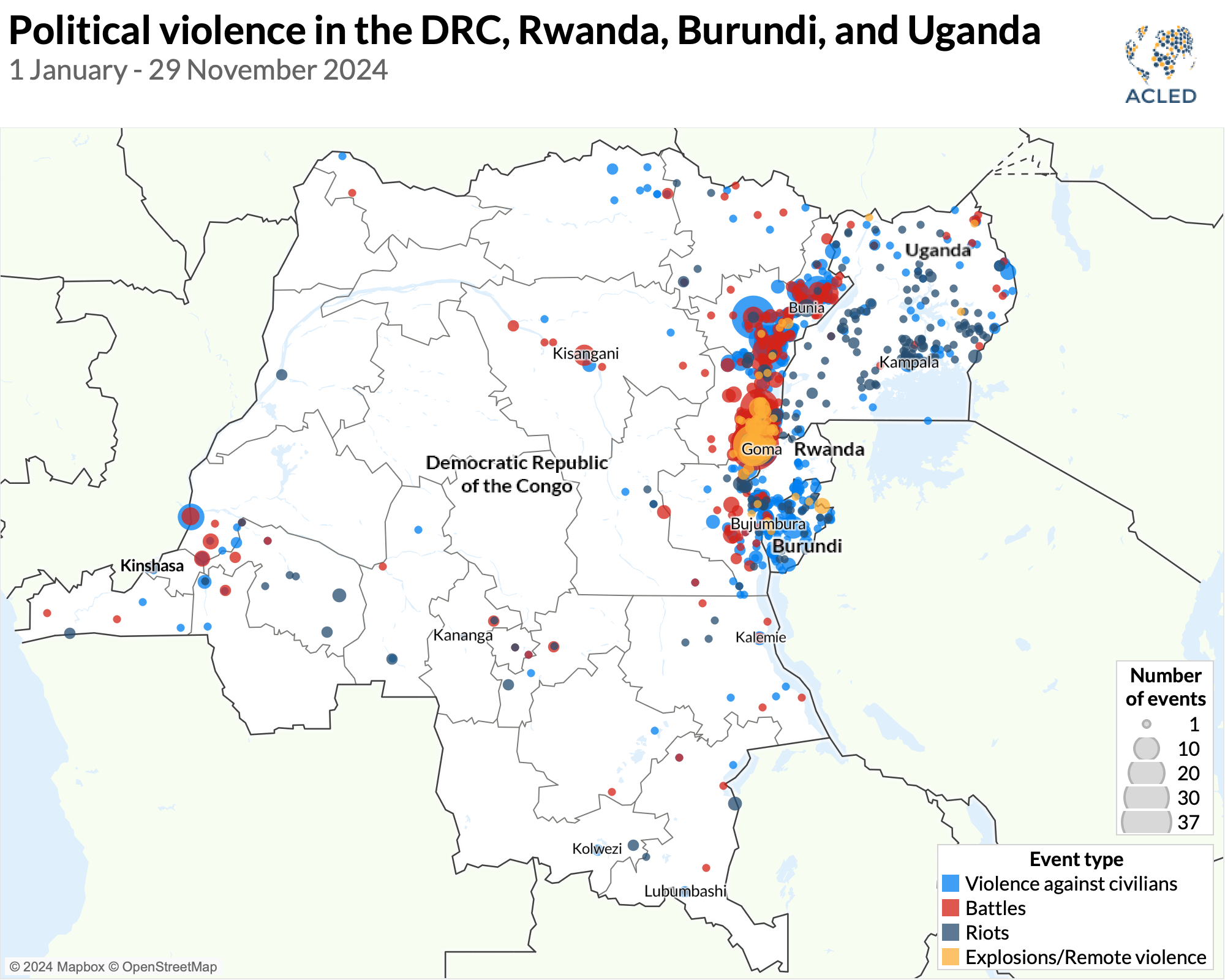

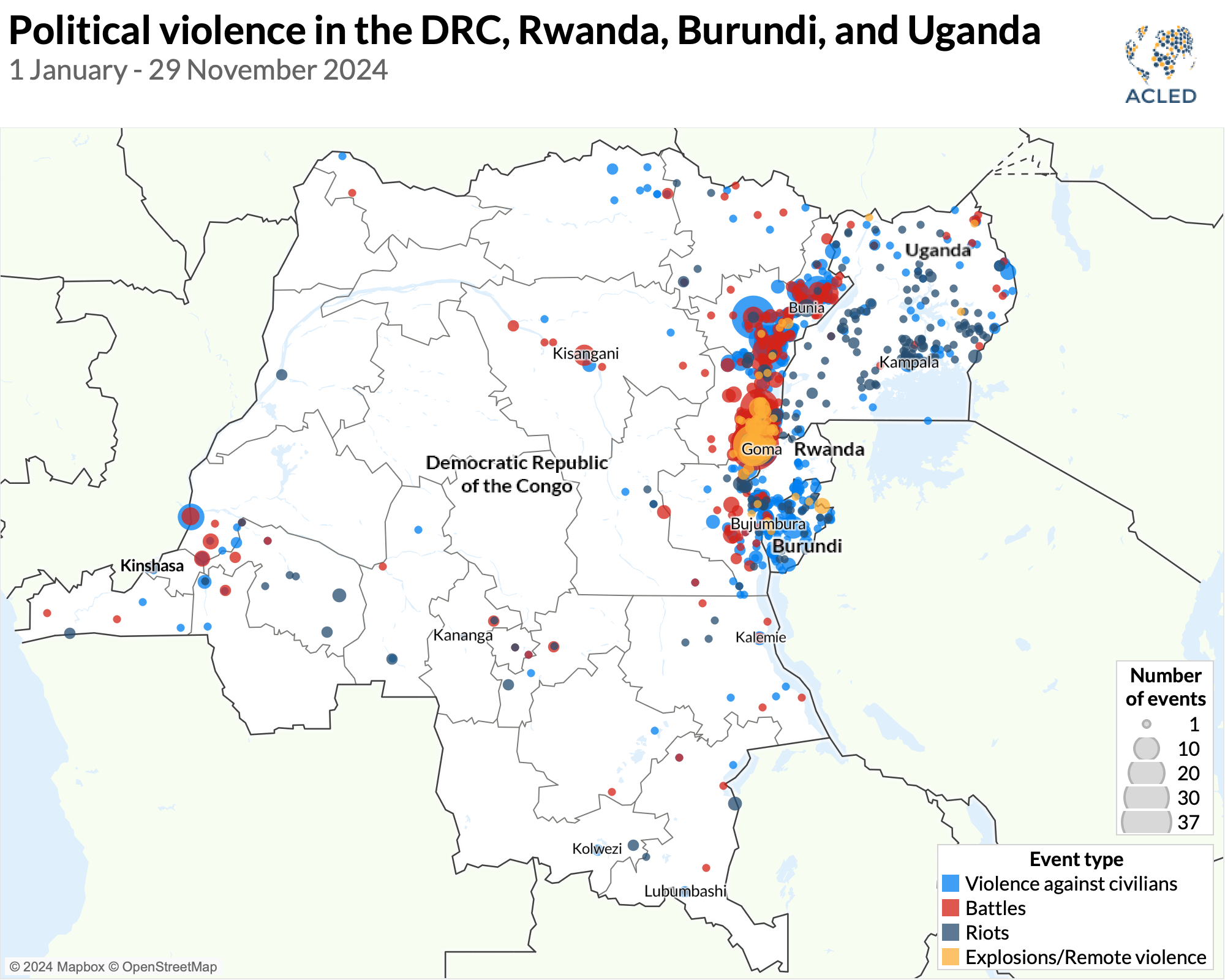

Conflicts in the Great Lakes region involved numerous military forces and foreign-backed armed groups in 2024, with violence involving the Rwanda-backed March 23 Movement (M23) rising. In the past year, the M23 and Rwandan military forces (RDF) aimed to broaden authority in North Kivu province, extract resources from mining sites, and generate revenue through taxation.1IPIS, ASSODIP, and DIIS, ‘Le M23 “Version 2”: Enjeux, motivations, perceptions et impacts locaux,’ p. 5, April 2024 The Congolese military forces (FARDC) drew upon additional regional alliances to combat the M23-RDF rebellion, operating alongside Burundian soldiers and Southern African Development Community (SADC) forces, along with an increasing number of local armed groups. Further north in Ituri, regional collaboration continued between Congolese soldiers and Ugandan military forces against the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) — an armed group initially formed with intentions to overthrow Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni but later shifting toward further alignments with the Islamic State and local power in eastern DRC.2Congo Research Group, ‘Inside the ADF Rebellion,’ Center on International Cooperation, New York University, November 2018 Amid the fighting among several militaries and allies within the DRC, violence by foreign armed groups declined in Burundi, Rwanda, and Uganda in 2024.

In 2024, Rwandan military forces (RDF) increased their direct involvement in the DRC, supporting the M23 in being the most violent non-state actor in the Great Lakes region for the second consecutive year. The RDF deployed around 3,000 to 4,000 troops into DRC to support the approximately 3,000 M23 fighters operating in North Kivu,3United Nations Security Council, ‘Letter dated 31 May 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,’ S/2024/432, 31 May 2024, pp. 10-15 aiding the M23 to use more advanced weapons and increase artillery strikes. The M23 and RDF also expanded the territory under their influence, especially around the economic hub of Goma, while also pushing westward into Walikale and further north compared to 2023.4Jean-Michel Bos, ‘Congo’s M23 rebels on the trail of mineral resources,’ Deutsche Welle, 8 November 2024 Overall, hostilities involving the M23-RDF led to an initial escalation in violence in the Great Lakes region during the first six months of 2024 before peace agreements between the Congolese and Rwandan governments brought a decline in violence by the second half of the year. The deployment of SADC and Burundian forces brought additional countries in the Great Lakes region into direct conflict with Rwanda, exacerbating already tense relations. Burundian soldiers had been sent into the DRC in past years but signed new agreements and bolstered troops in September 2023.5Sonia Rolley, ‘Over 1,000 Burundian soldiers covertly deploy in eastern Congo, internal UN report says,’ Reuters, 30 December 2023 The SADC mission brings further troop contributions from countries in the Great Lakes region, including Malawi and Tanzania, which deployed to North Kivu on 15 December 2023.6Mary Wambui, ‘EACRF completes withdrawal from Eastern DR Congo,’ The East African, 21 December 2023 Although SADC forces have taken a more defensive position against the M23 and RDF around the North Kivu capital of Goma, the operation complicates the SADC mission alongside the RDF in Mozambique.7Southern African Development Community, ‘Deployment of the SADC Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo,’ 4 January 2024 Additionally, the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the DRC continued its drawdown of forces over alleged failures to suppress violence in the region, popular demands to remove UN peacekeepers, and a broader regional trend of shifting toward regional and bilateral security partnerships.8Benjamin Petrini and Erica Pepe, ‘Peacekeeping in Africa: from UN to regional Peace Support Operations,’ International Institute for Strategic Studies, 18 March 2024; United Nations Affaires, ‘DR Congo President sets early withdrawal of UN peacekeepers, country will take reins of its destiny,’ 20 September 2023; Tlhompho Shikwambane, ‘The Disengagement of MONUSCO in DRC: Did the UN Peacekeeping Mission Fail in the DRC?’ Institute for Global Dialogue, 12 September 2024

In reprisal for the ongoing joint Congolese and Ugandan military forces under Operation Shujaa, the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) carried out increasingly lethal attacks on civilians — especially in more populated areas.9Uganda Broadcasting Corporation, ‘Gen Kainerugaba, DRC’s Gen Tshiwewe Hail Successes of Operation Shujaa,’ 1 November 2024; United Nations Security Council, ‘Letter dated 31 May 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,’ S/2024/432, 31 May 2024, pp. 6-8 While the ADF has long carried out high levels of civilian targeting in response to military operations,10United Nations Security Council, ‘Letter dated 31 May 2024 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council,’ S/2024/432, 31 May 2024, pp. 6-8 the number of civilians reportedly killed by the ADF surpassed 1,300 and rose over 17% in 2024 compared to 2023 — making the ADF the most violent actor toward civilians in the Great Lakes in 2024. To avoid direct conflict with the better-equipped joint military operations, the ADF continued with more mobile tactics through frequent changes in location and moving camp sites, resulting in a decline in clashes against opposing armed groups in 2024 compared to the previous year.

What to watch for in 2025

Albeit fragile, peace agreements and ceasefires between the DRC and Rwanda will likely diminish overall levels of violence in the Great Lakes region in 2025. Although spokespeople in Kigali long denied direct military deployment and support for the M23 rebellion, Rwandan operations have jeopardized funding and political support for other military operations, such as its bilateral deployment in Mozambique.11Romain Gras, ‘EU divided over financial support for Rwandan intervention in Mozambique,’ The Africa Report, 31 July 2024 Despite its threats to cut peacekeeping operations,12Federico Donelli, ‘Rwanda’s New Military Diplomacy,’ IFRI, N.31, 2022 Rwanda likely desires a resumption of positive relations with Western donors, which requires a conclusion to their military deployment in DRC and support for the M23. Reduced hostilities involving the M23 and RDF could permit the FARDC to pivot military attention and allied armed groups northward against the ADF. As hostilities involving the previous M23 rebellion declined in late 2013, the ADF suffered several setbacks at the hands of the Congolese forces, which inflicted heavy losses among the militant ranks and forced many fighters to flee outside the country or into forested areas.

Peace agreements remain especially delicate due to the inability or unwillingness of the Congolese and Rwandan governments to rein in violence by proxy groups. Continued clashes between the M23 and allies of the FARDC — especially the Wazalendo, a loose coalition of armed groups with a growing number of members since the resurgence of the M2313Coralie Pierret, ‘The “wazalendo”: Patriots at war in eastern DRC,’ Le Monde, 19 December 2023 — may spoil peace agreements similar to a previous surge of Wazalendo violence in late 2023. If hostilities involving the M23 and RDF decline, the Wazalendo coalition may lose a common enemy and give way to infighting between previously allied armed groups. Especially if the Congolese government negotiates or forces a withdrawal of M23 militants from areas of North Kivu province, this may give way to increased competition over access to strategic mining sites, control of roadways for tax revenue, and influence over local authorities.

Part of the negotiations between the DRC and Rwanda also involved promises by the Congolese government to eradicate the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR).14Security Council Report, ‘Great Lakes Region: Briefing and Consultations,’ 7 October 2024; Liam Karr, Kathryn Tyson, and Yale Ford, ‘Africa File, October 10, 2024: AUSSOM Challenges; Fano Counteroffensive; DRC Attacks FDLR; Mali’s Northern Challenges; Togo Border Pressure,’ Institute for the Study of War, 10 October 2024 The FDLR still holds links to the former Hutu regime in Rwanda, which carried out the 1993 genocide, and is frequently mentioned by Kigali as a major security threat.15See, for example, YouTube @RwandaTV, ‘President Kagame discusses Tshisekedi’s threats, M23 & the DRC, Burundi & FDLR alliance,’ 25 March 2024; Charles Onyango-Obbo, ‘Kagame: DRC has crossed red line, war won’t be in Rwanda,’ The East African, 26 February 2023 Given the integration of FDLR personnel into the FARDC and fighting under the Wazalendo coalition,16Ebuteli, ‘La résurgence du M23,’ August 2024; Human Rights Watch, ‘DR Congo: Army Units Aided Abusive Armed Groups,’ 18 October 2022; Maria Eriksson Baaz and Judith Verweijen, ‘The volatility of a half-cooked bouillabaisse: Rebel–military integration and conflict dynamics in the eastern DRC,’ African Affairs, October 203, pp. 563–582 the challenge for the FARDC involves removing key personnel from within their ranks and among allies without disrupting military operations or sparking additional retaliatory violence with the FDLR. An escalation of fighting between FDLR and Congolese forces could especially affect areas of Rutshuru territory where the FDLR has long maintained an active presence.17Human Rights Watch, ‘DR Congo: Army Units Aided Abusive Armed Groups,’ 18 October 2022

Despite the joint military efforts to eradicate the ADF, Operation Shujaa has yet to offer protection for civilians from increasingly deadly violence. As the ADF employs increasingly mobile and insurgent tactics, joint forces must find ways to adapt to the more itinerant maneuvering of the Islamic State affiliate. In 2024, reports also surfaced of Ugandan military support for M23 militants, which may erode the relationship between Congolese and Ugandan forces in the coming year and reduce their capacity for bilateral missions.18Lucy Fleming and Didier Bikorimana, ‘Two armies accused of backing DR Congo’s feared rebels,’ BBC, 9 July 2024 Without changes in military strategy and increased protection for civilians in more densely populated areas, civilian fatalities will likely escalate in the coming year — especially in hard-hit areas in North Kivu and Ituri provinces such as Beni, Mambasa, and Mamove.

Notwithstanding the challenges within DRC, military operations against rebel groups and bolstered border security will likely diminish the capacity for armed groups such as the ADF to carry out cross-border violence outside of Congolese territory in the coming year.19Africa News, ‘RDC : la frontière avec le Burundi submergée, un défi quotidien,’ 13 August 2024; Taarifa, ‘Rwanda and Uganda Agree to Strengthen Border Security and Community Awareness,’ 1 December 2024; Adam Ntwari, ‘Goma (RDC) : renforcement de la sécurité sur la frontière Goma-Gisenyi, crainte d’une possible fermeture des frontières entre la RDC et le Rwanda,’ SOS Médias, 22 January 2024 However, the likelihood of cross-border violence largely rests on negotiations between the Congolese and Rwandan governments, as well as the subsequent implications for Burundi and Uganda. If peace agreements and bargains reach unfavorable terms for one or more conflict parties in the coming year, countries in the Great Lakes are likely to resort to arming proxy groups to conduct cross-border attacks.20Burundi Human Rights Initiative, ‘An Operation of Deceit: Burundi’s secret mission in Congo,’ July 2022; Crisis Group, ‘Averting Proxy Wars in the Eastern DR Congo and Great Lakes,’ 23 January 2020

Une paix durable reste difficile à instaurer entre les groupes armés aux liens internationaux

En 2024, les conflits dans la région des Grands Lacs ont vu l’implication de nombreuses forces militaires et de groupes armés soutenus depuis l’étranger, avec une augmentation des violences impliquant le Mouvement du 23 mars (M23). Le M23 et les forces militaires rwandaises (RDF) ont cherché l’année dernière à étendre leur autorité dans la province du Nord-Kivu, en extrayant les ressources de certains sites miniers et en générant des revenus au moyen de taxes.1IPIS, ASSODIP et DIIS, « Le M23 « Version 2 » : Enjeux, motivations, perceptions et impacts locaux », p. 5, avril 2024 Les forces militaires congolaises (FARDC), elles, se sont appuyées sur des alliances régionales nouvelles pour combattre la rébellion du M23-RDF, en opérant notamment aux côtés des soldats burundais et des forces de la Communauté de développement de l’Afrique australe (SADC), ainsi que d’un nombre croissant de groupes armés locaux. Plus au nord, dans la province de l’Ituri, la coopération régionale s’est poursuivie entre les soldats congolais et les forces militaires ougandaises contre les Forces démocratiques alliées (ADF) — un groupe armé initialement formé avec l’intention de renverser le président ougandais Yoweri Museveni avant de s’aligner de manière plus marquée avec l’État islamique et les pouvoirs locaux dans l’est de la RDC.2Groupe d’étude sur le Congo, « Au cœur de la rébellion des forces démocratiques alliées (ADF) », Centre de coopération internationale, Université de New York, novembre 2018 Sur fond de combats entre plusieurs armées et groupes alliés en RDC, les violences impliquant des groupes armés étrangers ont diminué au Burundi, au Rwanda et en Ouganda en 2024.

En 2024, les RDF ont accentué leur implication directe en RDC, en appuyant les activités du M23 qui, pour la deuxième année consécutive, est l’acteur non étatique le plus violent de la région des Grands Lacs. Les RDF ont déployé entre 3 000 et 4 000 soldats en RDC pour soutenir les quelque 3 000 combattants du M23 opérant dans le Nord-Kivu,3Conseil de sécurité des Nations Unies, « Lettre datée du 31 décembre 2024, adressée au président du Conseil de sécurité par le Groupe d’experts sur la République démocratique du Congo », S/2024/432, 31 mai 2024, pp. 10-15 facilitant ainsi l’utilisation par le M23 d’armes plus avancées et l’augmentation des frappes d’artillerie. Le M23 et les RDF ont également élargi le territoire soumis à leur influence, en particulier autour du centre économique de Goma, tout en progressant vers l’ouest à Walikale et davantage vers le nord par rapport à 2023.4Jean-Michel Bos, « Les rebelles congolais du M23 sur la piste des ressources minérales », Deutsche Welle, 8 novembre 2024 Dans l’ensemble, les hostilités impliquant le M23-RDF ont entraîné une escalade initiale des violences dans la région des Grands Lacs au cours des six premiers mois de 2024, avant que les accords de paix entre les gouvernements congolais et rwandais n’entraînent une baisse des violences au cours du second semestre de l’année. Le déploiement des forces de la SADC et du Burundi a amené d’autres pays de la région des Grands Lacs à entrer en conflit direct avec le Rwanda, aggravant des relations déjà tendues.

Si des soldats burundais avaient déjà été envoyés en RDC ces dernières années, ils ont conclu de nouveaux accords et renforcé leurs effectifs sur place en septembre 2023.5Sonia Rolley, « Plus de 1 000 soldats burundais déployés secrètement dans l’est du Congo, selon un rapport interne de l’ONU », Reuters, 30 décembre 2023 La mission de la SADC apporte des contingents supplémentaires en provenance des pays de la région des Grands Lacs, notamment du Malawi et de la Tanzanie, qui avaient déjà déployé des troupes au Nord-Kivu le 15 décembre 2023.6Mary Wambui, « La Force régionale de la Communauté de l’Afrique de l’Est (EACRF) achève son retrait de l’est de la RD du Congo », The East African, 21 décembre 2023 Bien que les forces de la SADC aient adopté une position plus défensive contre le M23 et les RDF autour de Goma, la capitale du Nord-Kivu, l’opération complique la mission de la SADC et des RDF au Mozambique.7Communauté de développement de l’Afrique australe, « Déploiement de la mission de la SADC en République démocratique du Congo », 4 janvier 2024 En outre, la Mission de l’Organisation des Nations unies pour la stabilisation en RDC a continué à réduire ses effectifs en raison de son incapacité présumée à endiguer les violences dans la région, des demandes populaires de retrait des soldats de la paix de l’ONU et d’une tendance régionale plus large à s’orienter vers des partenariats régionaux et bilatéraux en matière de sécurité.8Benjamin Petrini et Erica Pepe, « Maintien de la paix en Afrique : de l’ONU aux opérations régionales de soutien de la paix », Institut international d’études stratégiques, 18 mars 2024; Affaires des Nations Unies, « Le président de la RD Congo fixe les conditions du retrait anticipé des forces de maintien de la paix de l’ONU, le pays prendra son destin en main », 20 septembre 2023; Tlhompho Shikwambane, « Le désengagement de la MONUSCO en RDC : La mission de maintien de la paix de l’ONU a-t-elle échoué en RDC ? » Institut pour le dialogue mondial, 12 septembre 2024

En représailles aux opérations menées conjointement par les forces militaires congolaises et ougandaises dans le cadre de l’opération Shujaa, les ADF ont mené des attaques de plus en plus meurtrières contre les populations civiles, notamment dans les zones les plus peuplées.9Uganda Broadcasting Corporation, « Gen Kainerugaba, le général Tshiwewe de la RDC salue les succès de l’opération Shujaa », 1er novembre 2024; Conseil de sécurité des Nations Unies, « Lettre datée du 31 mai 2024 adressée au Président du Conseil de sécurité par le Groupe d’experts sur la République démocratique du Congo », S/2024/432, 31 mai 2024, pp. 6-8 Bien que les ADF ciblent depuis longtemps un grand nombre de civils en réponse aux opérations militaires,10Conseil de sécurité des Nations Unies, « Lettre datée du 31 mai 2024, adressée au président du Conseil de sécurité par le Groupe d’experts sur la République démocratique du Congo », S/2024/432, 31 mai 2024, pp. 6-8 le nombre de civils qui auraient été tués par les ADF a été supérieur à 1 300 et a augmenté de plus de 17% en 2024 par rapport à 2023, ce qui fait des ADF l’acteur le plus violent à l’égard des civils dans la région des Grands Lacs en 2024. Afin d’éviter tout conflit direct avec des forces militaires conjointes mieux équipées, les ADF ont continué à utiliser des tactiques plus mobiles en changeant fréquemment leur emplacement et en déplaçant les sites de leurs campements, ce qui a entraîné une diminution des affrontements les opposant à d’autres groupes armés en 2024 par rapport à l’année précédente.

Ce qu’il faut surveiller en 2025

Bien que fragiles, les accords de paix et les cessez-le-feu entre la RDC et le Rwanda devraient réduire le niveau des violences dans la région des Grands Lacs en 2025. Si les représentants du gouvernement à Kigali ont longtemps nié tout déploiement militaire direct et tout soutien à la rébellion du M23, les opérations rwandaises ont nui au financement et au soutien politique d’autres opérations militaires dans lesquelles les forces rwandaises étaient impliquées, telles que leur déploiement bilatéral au Mozambique.11Romain Gras, « L’UE divisée sur le soutien financier à l’intervention rwandaise au Mozambique », The Africa Report, 31 juillet 2024 En dépit de ses menaces de réduction des opérations de maintien de la paix,12Federico Donelli, « La nouvelle diplomatie militaire du Rwanda », IFRI, n°31, 2022 le Rwanda souhaite vraisemblablement renouer des relations positives avec les bailleurs de fonds occidentaux, ce qui exigerait de mettre un terme à leur déploiement militaire en RDC et à leur soutien au M23. La réduction des hostilités liées au M23 et aux RDF pourrait permettre aux FARDC d’orienter leur effort militaire et l’action de groupes armés alliés vers le nord, pour lutter contre les ADF. Lorsque les hostilités impliquant la précédente rébellion du M23 avaient diminué à la fin de l’année 2013, les ADF avaient alors subi plusieurs revers de la part des forces congolaises, encaissant de lourdes pertes dans leurs rangs et provoquant la fuite de nombreux combattants à l’extérieur du pays ou dans certaines zones forestières.

La conclusion d’accords de paix reste particulièrement délicate en raison de l’incapacité ou du manque de volonté des gouvernements congolais et rwandais de mettre un terme aux violences commises par les groupes supplétifs. La poursuite des affrontements entre le M23 et les alliés des FARDC — notamment les wazalendo, une coalition informelle de groupes armés dont le nombre de membres a augmenté depuis la résurgence du M2313Coralie Pierret, « Le « wazalendo » : Patriotes en guerre dans l’est de la RDC », Le Monde, 19 décembre 2023 — pourraient faire échouer les accords de paix, comme lors de la précédente recrudescence des violences commises par les wazalendo fin 2023. Si les hostilités qui les opposent au M23 et aux RDF diminuent, les wazalendo pourrait perdre un ennemi commun et se livrer à des luttes intestines entre des groupes armés jusqu’alors alliés. Plus particulièrement si le gouvernement congolais parvient à négocier ou à contraindre les militants du M23 à se retirer de certaines zones de la province du Nord-Kivu, cela pourrait instaurer un climat de concurrence accrue pour l’accès à certains sites miniers stratégiques, le contrôle des routes nécessaires au prélèvement des recettes fiscales, et l’influence sur les autorités locales.

Une partie des négociations entre la RDC et le Rwanda comprenait également la promesse du gouvernement congolais de mettre fin aux activités des Forces démocratiques de libération du Rwanda (FDLR).14Rapport du Conseil de sécurité, « Région des Grands Lacs : Briefing and Consultations », 7 octobre 2024; Liam Karr, Kathryn Tyson et Yale Ford, « Africa File », 10 octobre 2024 : Défis AUSSOM ; Contre-offensive de Fano ; La RDC attaque les FDLR ; Les défis du nord du Mali ; Pression à la frontière togolaise », Institut pour l’étude de la guerre, 10 octobre 2024 Les FDLR sont toujours liées à l’ancien régime hutu du Rwanda, qui a perpétré le génocide de 1993, et sont fréquemment citées par Kigali comme une menace majeure pour la sécurité du pays.15Consulter, par exemple, YouTube @RwandaTV, « Le président Kagame discute des menaces de Tshisekedi, du M23 et de l’alliance entre la RDC, le Burundi et les FDLR », 25 mars 2024; Charles Onyango-Obbo, ‘Kagame : La RDC a franchi la ligne rouge,la guerre n’aura pas lieu au Rwanda », The East African, 26 février 2023 Étant donné la présence de membres des FDLR au sein des FARDC et les combats menés dans le cadre de la coalition « Wazalendo »,16Ebuteli, « La résurgence du M23 », août 2024; Human Rights Watch, « RD Congo : Des unités de l’armée ont aidé des groupes armés responsables d’exactions », 18 octobre 2022; Maria Eriksson Baaz et Judith Verweijen, « La volatilité d’une bouillabaisse mi-cuite : Intégration militaro-rebelle et dynamique des conflits dans l’est de la RDC », African Affairs, octobre 203, pp. 563-582 la difficulté pour les FARDC consistera à écarter des membres clés de leurs rangs et de leurs alliés sans perturber leurs opérations militaires ni déclencher de nouvelles représailles violentes de la part des FDLR. Une escalade des combats entre les FDLR et les forces congolaises pourrait en effet avoir des conséquences particulièrement graves sur les zones du territoire de Rutshuru où les FDLR maintiennent depuis longtemps une présence active.17Human Rights Watch, RD Congo : Des unités de l’armée ont aidé des groupes armés responsables d’exactions », 18 octobre 2022

Malgré les efforts militaires conjoints pour éradiquer les ADF, l’opération Shujaa n’a pas encore permis de protéger les civils d’une violence de plus en plus meurtrière. Alors que les ADF emploient des tactiques de plus en plus mobiles et insurrectionnelles, les forces conjointes doivent trouver des moyens de s’adapter aux manœuvres davantage itinérantes de l’affilié de l’État islamique. En 2024, des rapports ont également fait état d’un soutien militaire ougandais aux militants du M23, ce qui pourrait éroder les relations entre les forces congolaises et ougandaises au cours de l’année à venir et réduire leur capacité à mener des missions bilatérales conjointes.18Lucy Fleming et Didier Bikorimana, « Deux armées accusées de soutenir les rebelles redoutés de la RD Congo », BBC, 9 juillet 2024 En l’absence de changements en matière de stratégie militaire et de mesures de protection accrue des civils dans les zones les plus densément peuplées, il est probable que le nombre de victimes civiles augmente au cours de l’année à venir, en particulier dans les zones les plus durement touchées des provinces du Nord-Kivu et de l’Ituri, telles que Beni, Mambasa et Mamove.

En dépit des difficultés rencontrées en RDC, les opérations militaires menées contre les groupes rebelles et le renforcement de la sécurité aux frontières réduiront probablement la capacité des groupes armés tels que les ADF à commettre des violences transfrontalières en dehors du territoire congolais au cours de l’année à venir.19Africa News, « RDC : la frontière avec le Burundi submergée, un défi quotidien », 13 août 2024; Taarifa, « Le Rwanda et l’Ouganda conviennent de renforcer la sécurité des frontières et la sensibilisation des communautés », 1er décembre 2024; Adam Ntwari, « Goma (RDC) : renforcement de la sécurité sur la frontière Goma-Gisenyi, crainte d’une possible fermeture des frontières entre la RDC et le Rwanda », SOS Médias, 22 janvier 2024 La probabilité d’une violence transfrontalière dépend toutefois largement des négociations entre les gouvernements congolais et rwandais, ainsi que des implications susceptibles d’en découler pour le Burundi et l’Ouganda. Si les accords de paix et les négociations aboutissent à des conditions défavorables pour une ou plusieurs parties au conflit au cours de l’année à venir, les pays de la région des Grands Lacs risquent de se tourner vers l’armement de groupes supplétifs pour mener des attaques transfrontalières.20Initiative des droits de l’homme au Burundi, « Une opération de tromperie : Mission secrète du Burundi au Congo, juillet 2022; Crisis Group, « Averting Proxy Wars in the Eastern RD Congo and Great Lakes », 23 janvier 2020

Read More

To find out more, read our December 2024 Conflict Index results.