Conflict Watchlist 2025 | Myanmar

Decisive year ahead for resistance groups in Myanmar as they threaten new territories

Posted: 12 December 2024

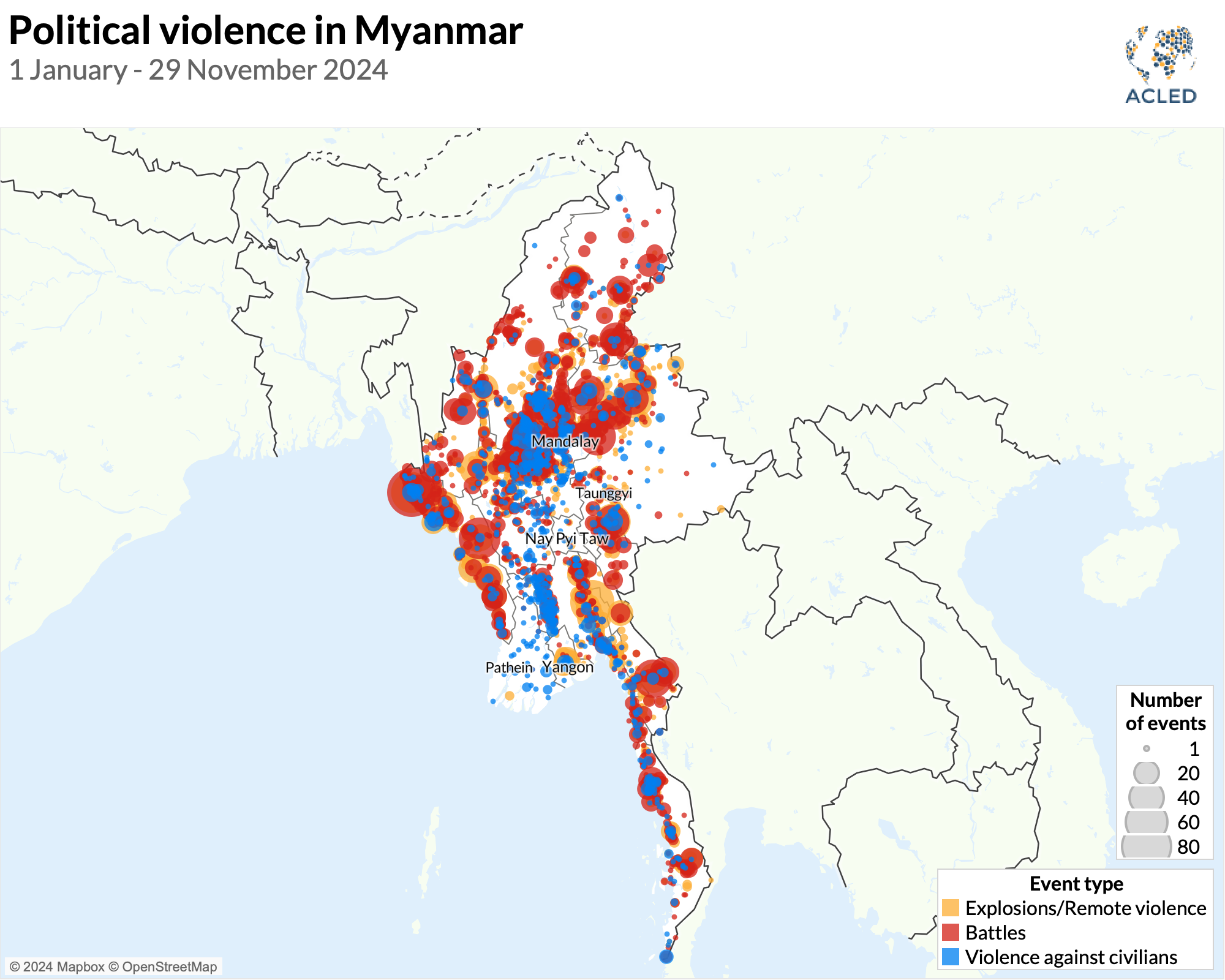

Despite the military’s ongoing counteroffensive campaigns, resistance groups opposing military rule in Myanmar made substantial strategic and territorial gains in 2024. This notably included the capture of the Northeastern Regional Military Command (RMC) in Lashio — one of 14 top-level military headquarters in the country — for the first time in the country’s history. The Brotherhood Alliance, comprised of the Myanmar National Truth and Justice Party/Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNTJP/MNDAA), Palaung State Liberation Front/Ta’ang National Liberation Army (PSLF/TNLA), and United League of Arakan/Arakan Army (ULA/AA), revived last year’s Operation 1027 in late June, following a short-lived ceasefire under the Haigen Agreement brokered by China in January. The MNTJP/MNDAA’s capture of Lashio town in northern Shan state and the PSLF/TNLA’s capture of Mogoke, a major ruby mining hub in Mandalay region, dealt both symbolic and tactical blows to the military. Residents in Mogoke celebrated as resistance groups entered the town, while pro-military supporters called for the resignation of the military leadership after the fall of the Northeastern RMC in Lashio.1The Irrawaddy, ‘TNLA, PDF Seize Myanmar’s Ruby Hub Mogoke From Junta,’ 25 July 2024; Facebook @KhitThitNews, ’ 3 August 2024; Al Jazeera, ‘Min Aung Hlaing admits pressure after Myanmar anti-coup forces claim base,’ 6 August 2024 These gains by the Brotherhood Alliance began a debate about its ability to directly threaten Mandalay city, which is 277 kilometers away from the military’s capital, Nay Pyi Taw, and home to a large civilian population.2Nayt Thit, ‘As Resistance Enters Mandalay, is Myanmar’s Second City on Brink of Falling?,’ The Irrawaddy, 3 September 2024

Meanwhile, the ULA/AA continued its operations in Rakhine state. It captured 14 towns and increasingly threatened the Western MRC based in Ann township, one year after the collapse of the humanitarian ceasefire with the military in November 2023.3Radio Free Asia, ‘Arakan Army attacks junta, ending year-long ceasefire in Rakhine state,’ 14 November 2023 In northern Myanmar, the Kachin Independence Organization/Kachin Independence Army (KIA/KIO) and its allies reopened battlefronts with the military in March with the launch of Operation 0703, named after the anniversary of their revolution. They have captured five towns since, including the rare-earth mining hubs of Chipwi and Pangwa towns in Kachin state. These groups demonstrated their growing military capabilities by shooting down helicopters, sinking navy boats, and seizing heavy weaponry during their territorial advances. The People’s Defense Forces also made gains in Sagaing region, capturing Kawlin and Pinlebu towns, significant positions for transporting supplies to major battlefronts. In the first 11 months of 2024, ACLED records 277 incidents in which resistance groups have captured towns and bases from the military. This is a striking increase from 62 locations captured by resistance forces in the entire 2023.

In response to mounting losses, the military activated its conscription law in February to combat its deep unpopularity and coerce youths into military service, further fragmenting an increasingly militarized society.4Sebastian Stragio, ‘Myanmar Junta to Begin Enforcing Military Conscription Law,’ The Diplomat, 12 February 2024 Males aged between 18 and 35 were, and continue to be, called to serve by law, including those outside the country, while those aged between 35 and 60 are being recruited into “anti-terrorism” people’s security teams.5The Irrawaddy, ‘Depleted Myanmar Military to Recruit Men Aged Over 35 for “Security” Teams,’ 27 August 2024 Beyond enforcing the conscription law, the military has pushed many poorly trained civilians to the front lines. In 2024, thousands of civilians, including people from the Rohingya minority, were forcibly recruited and used as human shields in combat.6The Irrawaddy, ‘Myanmar Junta Steps Up Conscription With Forced Abductions After Thingya,’ 25 April 2024; Shaikh Azizur Rahman, ‘Young Rohingya men abducted, forced into “human shield” roles by Myanmar military,’ Voice of America, 30 May 2024 On 12 March, over 90 Rohingya forced recruits were reportedly killed in an armed clash between the military and the ULA/AA near Ah Ngu Maw village. Rohingya civilians remain the most persecuted people in Myanmar; are denied citizenship rights; and are subject to atrocities by the military, the ULA/AA, and Rohingya armed groups.

In 2024, the military repeatedly resorted to targeting civilians with extreme violence as its multiple counteroffensives to retake lost territory failed nationwide. While doing so, the military continued to evoke plans to hold elections, a key part of the manifesto it published following the 2021 coup.7Radio Free Asia, ‘Myanmar junta commits to staggered 2025 election,’ 26 August 2024 Its attempts to collect census data — which were not anonymized and more accurately resembled voter list data — were resisted by the public.8Frontier Myanmar, ‘Losing count: Chaotic census kicks off,’ 11 October 2024 Any elections would be severely circumscribed, poorly administered, reach few citizens, and have limited participation from only military-allied politicians. The military refuses to respond to key negotiating issues such as governance structures and bottom-up federalism that resistance groups have called for.9Khonumthung News, ‘9 state/ethnic representative councils including EROs to work together for stronger federal union,’ 24 September 2024 The election talk is widely seen as an attempt at an exit strategy for the military.10Joshua Lipes and RFA Burmese, ‘EXPLAINED: Why does Myanmar’s junta want to hold elections?,’ Radio Free Asia, 28 August 2024 The military leadership has been criticized by even its supporters for its weakness and mistakes, and resistance groups have yet to acknowledge any genuine attempt to resolve the conflict from the military side; rather, the military’s actions since the 2021 coup have further entrenched the cycle of violence.

What to watch for in 2025

Resistance groups in Myanmar are likely to continue focusing on areas adjacent to their recent territorial gains to consolidate their new holdings, expand their administration and revenue, and better threaten Nay Pyi Taw. This may include opening new battlefronts in central Myanmar, such as in Mandalay, Sagaing, and Magway regions. Some resistance groups fighting alongside the Brotherhood Alliance have announced the relocation of their troops to central Myanmar.11Saw Lwin, ‘Resistance Armies Poised to Move On to Central Myanmar,’ The Irrawaddy, 31 October 2024 Securing strategic towns in Mandalay and Magway regions will sustain and advance the resistance groups’ operations. Larger groups could provide resources to the local groups fighting in those areas or coordinate military actions with them.

On the other hand, the military is expected to push ahead with its attempt to hold elections in 2025, although this remains an unlikely scenario. Military leaders continue to approach political parties and some of the ethnic armed groups that are currently not fighting them, asking them to support potential elections. They have also invited opponents to disarm and enter the elections as political parties and appealed to China for support.12Sui-Lee Wee, ‘Myanmar’s Military Asks Rebels to Stop Fighting and Join in Elections,’ The New York Times, 27 September 2024; Antonio Graceffo, ‘China Calls for Elections to Defuse Myanmar Civil War,’ Geopolitical Monitor, 5 September 2024 However, those opposition groups led by the National Unity Government (NUG) have mobilized to boycott military-led elections. The KIA/KIO has also declared it will not accept elections in areas under its control. If elections are pursued in 2025, this will result in associated violence, likely affecting civilians.

The military may instead employ a ‘dual strategy’ to increase military pressure on the resistance groups while inviting them to enter the political process. With China now publicly backing military rule in Myanmar since Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s visit in August,13Ck Tan, ‘China’s Wang Yi urges war-torn Myanmar to seek ‘political reconciliation,’ Nikkei Asia, 15 August 2024; Ingyin Naing, ‘China backs Myanmar military amid growing border tensions,’ Voice of America, 8 November 2024 the military could try to increase its combat, economic, and diplomatic power to subdue its large and diverse opposition. For their part, the NUG and allied resistance groups have outlined six conditions for negotiations with the military, including demanding the military withdraw from politics — a condition unlikely to materialize soon.

Civilians will continue to suffer under the military’s ongoing repression. Under increasing military pressure on the ground, the military will persevere in its indiscriminate aerial attacks on civilian populated areas in an effort to undermine the opposition’s support base and destroy their morale. The military is likely to continue its mass atrocities in areas close to its besieged RMCs, including in Sagaing region, which it can quickly reinforce with ground troops, artillery, and air support. As a result, the humanitarian situation will remain dire, millions of people will remain or be repeatedly displaced, and large swaths of the population will continue to suffer under both military repression and economic collapse.

China will possibly take a more active role in Myanmar’s conflict. Beijing has pressured resistance groups operating along the border to stop fighting against the military, retreat from certain areas such as Lashio, and join peace talks. It has also demanded the United Wa State Party/United Wa State Army — the most powerful non-Bama ethnic actor in Myanmar and a significant supplier of weapons to the resistance — stop its support. Additionally, China has closed major border crossings following the takeover of Lashio town by the MNTJP/MNDAA and the capture of Chipwi and Pangwa rare-earth mining towns by the KIO/KIA. These actions aim to cut off essential supplies such as medicine, electricity, and internet access. China conducted live-fire exercises at the border with northern Shan state in October as a show of force. In a further escalation, Chinese authorities appear to have detained the MNTJP/MNDAA leader and placed him under house arrest, demanding the withdrawal of troops from Lashio.14Radio Free Asia, ‘Leader of rebel army detained in China’s Yunnan province,’ 18 November 2024 China has also offered to establish joint security companies with the military under the guise of protecting its investments,15Maung Kavi, ‘Myanmar Junta Planning Joint Security Firm with China,’ The Irrawaddy, 15 November 2024 thereby increasing its military presence in Myanmar.

Amid China’s growing public support for the military, resentment among the local population is expected to grow. Following China’s pressure on armed groups in northern Myanmar, a bomb explosion was directed at the Chinese Consulate in Mandalay on 18 October. No group claimed responsibility for the attack, and it was possibly a false flag operation. Despite China’s efforts, resistance groups have remained resolute, with the KIO/KIA pledging to continue its military operations in alliance with other revolutionary forces in the fight against the military junta. The group most likely to succumb to Chinese pressure first is the MNTJP/MNDAA, as it is under intense pressure to retreat from Lashio town, but this is a highly dynamic, unfolding situation. With control over strategic towns, border gates, and strong public support, in 2025, resistance groups will likely better coordinate to consolidate their gains and expand new operations against the junta, undeterred by external and military pressure.

Read More

Myanmar ranks second in the latest edition of our Conflict Index. To find out more, read our December 2024 Conflict Index results, or see our dedicated Myanmar infographic.