Conflict Watchlist 2025 | The Sahel and Coastal West Africa

Conflict intensifies and instability spreads beyond Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger

Posted: 12 December 2024

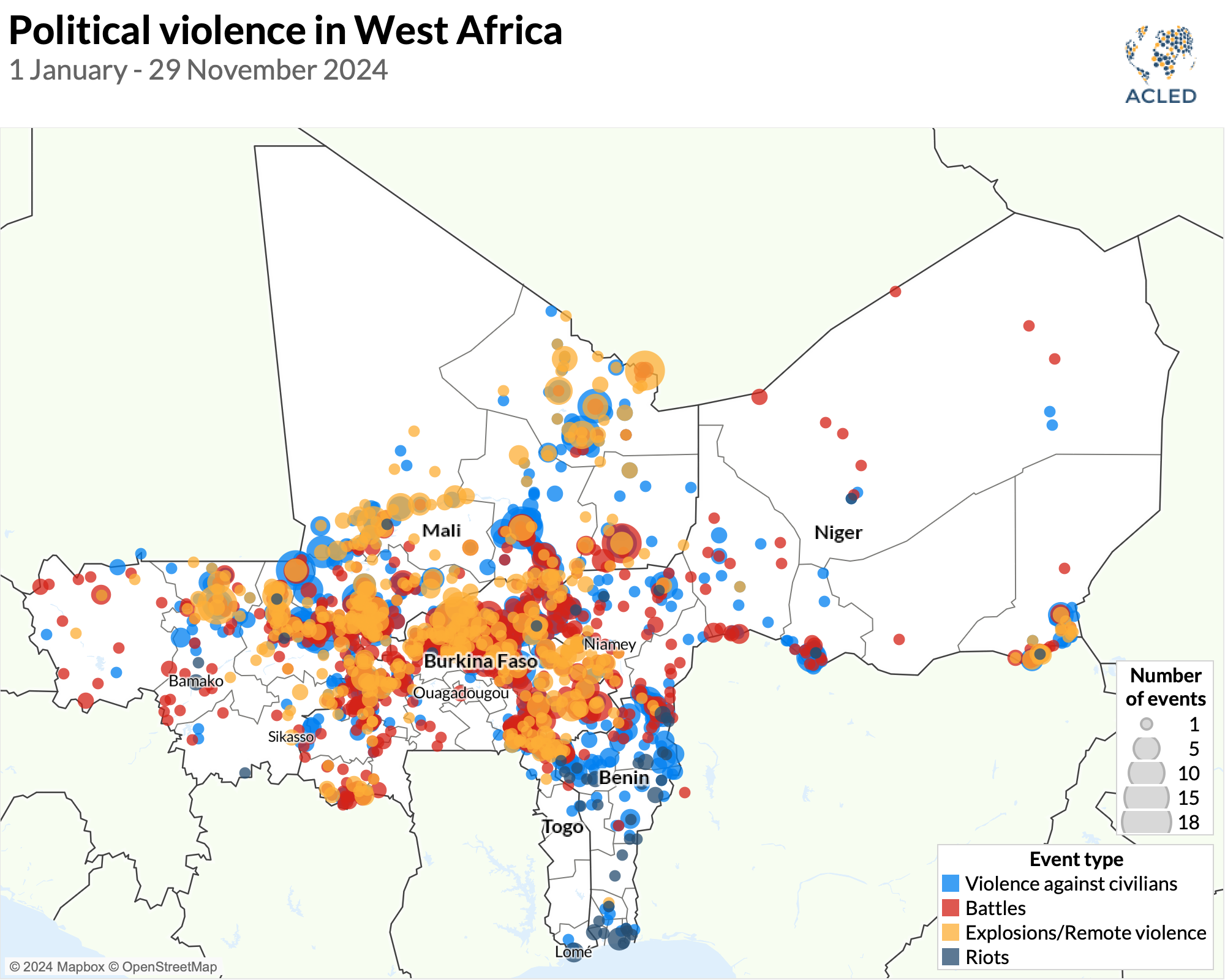

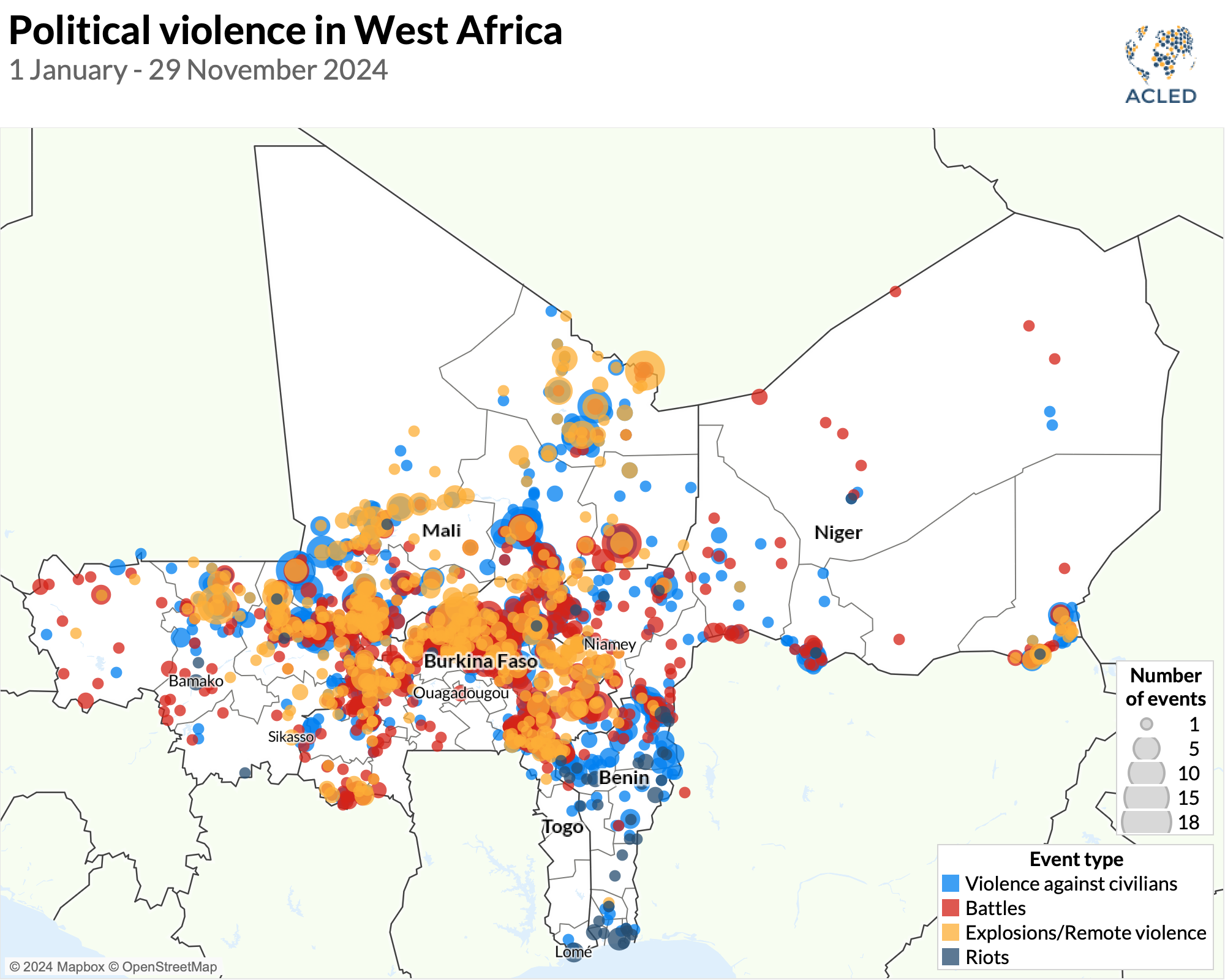

In 2024, the central Sahel countries of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger continued to experience persistent high levels of violence. These countries grapple with an entrenched jihadist insurgency that continues to expand through the activities of the al-Qaeda-affiliated Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) and the Islamic State Sahel Province (IS Sahel). In 2024, JNIM and IS Sahel launched a spate of high-impact or mass-casualty attacks that targeted state forces, militias, and civilians with increasing lethality. In particular, the increase in air and drone strikes, IED attacks, rocket and mortar shellings underline a clear change in combat tactics.

Burkina Faso is engulfed in escalating armed conflict. JNIM launched large-scale offensives that involved a series of mass killings of soldiers, Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland (VDP), and civilians, resulting in the death of hundreds of people in the Sahel, Center-North, and East regions. JNIM’s strong and violent presence in Burkina Faso’s eastern regions has transnational implications: In the coastal states of Benin and Togo, where JNIM has expanded its operations and consolidated its presence, violence has taken on new characteristics and proportions.

In Mali, Tuareg and Arab rebels of the Strategic Framework for the Defense of the People of Azawad (CSP-DPA) and JNIM militants defeated Wagner Group mercenaries and Malian troops (FAMa) near Tin Zaouatene, Kidal region, in late July. It marked the Wagner Group’s largest defeat on the African continent to date, after which JNIM launched a widespread offensive and coordinated attacks on Bamako. The defeat of Wagner and FAMa at Tin Zaouatene was followed by a sophisticated attack on Bamako in which JNIM fighters temporarily took control of the capital city’s international airport. This raid was a major symbolic setback for Wagner and FAMa, which had previously seized the rebel stronghold of Kidal in November 2023.

JNIM is deliberately trying to destabilize both the Burkinabe and Malian military regimes, as the group has clearly expressed in its media and propaganda in the wake of high-impact attacks. The group described the attacks in Bamako and Nassougou as disrupting the peace of the Malian regime and its Wagner allies1X @SimNasr, 17 September 2024 and shaking the ruling elite in Ouagadougou.2X @SimNasr, 13 August 2024 In the wake of the Barsalogho massacre in August, when JNIM reportedly killed hundreds of people building trenches,3Youri van der Weide et al., ‘Barsalogho Massacre: How Defensive Trenches Became a Mass Grave,’ Bellingcat, 4 September 2024 a senior JNIM figure publicly criticized Burkinabe President Ibrahim Traoré for his involvement in mobilizing the civilian population in the fight against the militants.4X @SimNasr, 3 September 2024

For its part, Niger also faces increasing security challenges from multiple militant groups, particularly IS Sahel. IS Sahel consolidated its presence along the Niger-Mali border, in the north of the Dosso region, and through the infiltration of Kebbi and Sokoto states in northwestern Nigeria. These maneuvers were carried out by local Nigerian IS Sahel recruits, locally referred to as ‘Lakurawa’ in the Hausa language, as Nigerian authorities acknowledged in early November 2024.5Monsuroh Abdulsemiu, ‘DHQ declares “9 Lakurawa terrorists” wanted,’ The Cable, 7 November 2024 The response to this acknowledgment came swiftly as Nigerien forces carried out airstrikes, killing 10 Lakurawa militants on 19 November near the border village of Manseyka, Tahoua region.6Forces Armées Nigériennes – FAN, ‘Bulletin des activités opérationnelles des FDS au cours de la période du 17 au 20 Novembre 2024,’ 20 November 2024; Le Souffle de Maradi, ‘#NIGER/#NIGERIA/#DÉFENSE : UNE DIZAINE DE #LAKURAWA MIS HORS D’ÉTAT DE NUIRE PRÈS DE #MUNTSEKA !,’ 22 November 2024 Meanwhile, IS Sahel’s jihadist rival, JNIM, has been active in the southwestern parts of Niger’s Tillaberi region and has significantly expanded its operations in the southern part of Dosso, along the borders with Benin and Nigeria. In October, JNIM carried out its first recorded attack in the northern Agadez region in a clash with security forces near Assamakka. An attack at the end of October on a security checkpoint in Niamey’s Seno quarter shows that JNIM is capable of carrying out attacks by exploiting the vulnerabilities of Sahelian capitals — and that it has established a stable operational presence in the surroundings of Niamey and Bamako.

What to watch for in 2025

As we move into 2025, the central Sahel continues to experience persistent high levels of violence, with instability spreading geographically and evolving in nature. Particularly in Burkina Faso and Mali, state forces have reacted to jihadist groups’ escalating activity with retaliatory violence against civilians in an attempt to deter the civilian population from providing support to armed groups. Jihadist groups, for their part, are stepping up their community outreach and preaching efforts. By presenting themselves as protectors against state forces, Wagner mercenaries, and pro-government militias, JNIM and IS Sahel are consolidating their influence over the civilian population, which is increasingly trapped in areas under jihadist control.

The protracted conflict in the Sahel is increasingly affecting urban centers. This reflects broader regional dynamics in which rapid urbanization and the strategic targeting of these areas maximize the impact of militant attacks. Recent attacks on the capital cities of Bamako and Niamey demonstrate growing vulnerability in these urban environments.7Jean-Hervé Jezequel, ‘The 17 September Jihadist Attack in Bamako: Has Mali’s Security Strategy Failed?,’ ICG, 24 September 2024 The overlap between urban and rural areas creates complex security challenges as militant groups use less secure urban outskirts as gateways. Furthermore, technological advances in the conflict, particularly the increasing use of drone warfare and remote violence by non-state actors, pose an additional risk to human security and critical infrastructure.

Indeed, the use of drones by both state actors and non-state armed groups, including Wagner, JNIM, and CSP-DPA,8X @MENASTREAM, 1 January 2024; David Baché, ‘Mali: les rebelles du CSP combattent désormais avec des drones,’ RFI, 12 September 2024; Benjamin Roger and Emmanuel Grynszpan, ‘Dans le nord du Mali, les drones ukrainiens éclaircissent l’horizon des rebelles,’ Le Monde, 10 October 2024 represents a significant change to a conflict that had been characterized by traditional and rudimentary guerrilla warfare. The use of modified commercial drones for offensive operations is becoming more sophisticated and widespread as jihadist groups employ drone warfare not only for surveillance and reconnaissance but also for targeted strikes through drone-delivered explosives, including kamikaze drones. These drone warfare capabilities represent a major tactical advance; although they are emergent, they could be refined to extend operational reach. These capabilities enable precision strikes (in combination with other forms of remote violence), improved surveillance and monitoring, and more impactful media and propaganda operations.

Emerging alliances between Tuareg, Toubou, and other rebels across the borders of Mali and Niger, along with coalition-building between rebels within Niger, represent new variables in the conflict equation. Although these groups currently have limited influence compared to their jihadist counterparts, they could eventually preoccupy or overwhelm the military forces, which already face numerous serious threats.

The ripple effects of this regional instability can be observed in the neighboring states of Benin and Togo, where the advance of JNIM operations presents a deliberate and strategic expansion rather than mere spillover. Similarly, the border areas between Niger and Nigeria are becoming focal points of both JNIM and IS Sahel activity. These areas have served as retreats and safe havens for the two groups. Although both JNIM and IS Sahel are coercively influencing the local populations, JNIM is likely to continue its violent campaign to consolidate its influence in these border areas, especially in the south of Niger’s Dosso region, where the group claimed its first operations in 2024. Meanwhile, the exposure of IS Sahel’s presence in northwestern Nigeria puts pressure on both Nigeria and Niger to take military action, which could also provoke a response from IS Sahel militants who, covertly and overtly, have been infiltrating the region largely unimpeded since at least 2018. The challenge for the region’s governments will be to deal with these evolving threats in a way that prevents further destabilization and protects vulnerable populations from the violence that continues to spread across their territories.

Le conflit s’intensifie et l’instabilité se propage au-delà du Burkina Faso, du Mali et du Niger

En 2024, les pays du centre du Sahel, à savoir le Burkina Faso, le Mali et le Niger, ont continué de connaître des niveaux élevés de violence. Ces pays sont aux prises avec une insurrection djihadiste bien ancrée qui ne cesse de s’étendre grâce aux activités du Groupe de soutien à l’islam et aux musulmans (GSIM), affilié à Al-Qaïda, et de l’ État islamique dans le Grand Sahara (EIGS). En 2024, le GSIM et l’EIGS ont lancé une vague d’attaques d’ampleur et meurtrières, ciblant les forces étatiques, les milices et les civils avec une létalité grandissante. Tout particulièrement, l’augmentation des frappes aériennes et de drones, des attaques à l’EEI, ainsi que des tirs de roquettes et de mortiers, souligne un changement clair dans leurs tactiques de combat.

Le Burkina Faso est plongé dans un conflit armé de plus en plus intense Le GSIM a lancé des offensives à grande échelle marquées par une série de massacres de soldats, de Volontaires pour la défense de la patrie (VDP) et de civils, entraînant la mort de centaines de personnes dans les régions du Sahel, du Centre-Nord et de l’Est. La puissante et violente présence du GSIM dans les régions orientales du Burkina Faso a également des répercussions transfrontalières : Dans les États côtiers du Bénin et du Togo, où le GSIM a étendu ses opérations et consolidé sa présence, la violence a pris de nouvelles formes et de nouvelles proportions.

Au Mali, les rebelles touaregs et arabes du Cadre stratégique pour la défense du peuple de l’Azawad (CSP-DPA) et les militants du GSIM ont infligé une défaite aux mercenaires du groupe Wagner et aux troupes maliennes (FAMa) près de Tin Zaouatene, dans la région de Kidal, à la fin du mois de juillet. Il s’agit de la plus grande défaite du groupe Wagner sur le continent africain à ce jour, après quoi le GSIM a lancé une offensive généralisée et des attaques coordonnées sur Bamako. La défaite du groupe Wagner et des FAMa à Tin Zaouatene a été suivie d’une attaque élaborée contre Bamako, au cours de laquelle les combattants du GSIM ont temporairement pris le contrôle de l’aéroport international de la capitale. Ce raid a constitué un revers symbolique majeur pour le groupe Wagner et les FAMa, qui s’étaient emparés du fief rebelle de Kidal en novembre 2023.

Le GSIM cherche délibérément à déstabiliser les régimes militaires burkinabé et malien, comme il l’a clairement relayé dans ses médias et sa propagande à la suite d’attaques à fort impact. Le groupe a décrit les attaques de Bamako et Nassougou comme une atteinte à la paix du régime malien et de ses alliés9X @SimNasr, 17 septembre 2024 du groupe Wagner et une menace contre l’élite dirigeante à Ouagadougou.10X @SimNasr, 13 août 2024 Suite au massacre de Barsalogho en août, au cours duquel le GSIM aurait tué des centaines de personnes chargées de construire des tranchées,11Youri van der Weide et al., ‘Barsalogho Massacre: Comment les tranchées défensives sont devenues un charnier’ Bellingcat, 4 septembre 2024 un haut responsable du GSIM a publiquement critiqué le président burkinabé Ibrahim Traoré pour son implication dans la mobilisation de la population civile dans la lutte contre les militants.12X @SimNasr, 3 septembre 2024

De son côté, le Niger est également confronté à des défis sécuritaires croissants de la part de plusieurs groupes militants, en particulier l’EIGS. L’EIGS a consolidé sa présence le long de la frontière entre le Niger et le Mali, dans le nord de la région de Dosso, et par l’infiltration des États de Kebbi et de Sokoto dans le nord-ouest du Nigeria. Ces manœuvres ont été menées par des recrues nigérianes locales de l’EIGS, appelées localement « Lakurawa » en langue haoussa, comme l’ont reconnu les autorités nigérianes au début du mois de novembre 2024.13Monsuroh Abdulsemiu, « Le QG déclare que « 9 terroristes de Lakurawa » sont recherchés », The Cable, 7 novembre 2024 La réponse à cette reconnaissance n’a pas tardé : les forces nigériennes ont mené des frappes aériennes, tuant 10 militants Lakurawa le 19 novembre près du village frontalier de Manseyka, dans la région de Tahoua.14Forces Armées Nigériennes – FAN, Bulletin des activités opérationnelles des FDS au cours de la période du 17 au 20 Novembre 2024, 20 Novembre 2024; Le Souffle de Maradi, #NIGER/#NIGERIA/#DÉFENSE : UNE DIZAINE DE #LAKURAWA MIS HORS D’ÉTAT DE NUIRE PRÈS DE #MUNTSEKA !,’ 22 novembre 2024 Parallèlement, le GSIM, rival djihadiste de l’EIGS, a mené des actions dans le sud-ouest de la région de Tillaberi au Niger et a considérablement étendu ses opérations dans le sud de Dosso, le long des frontières avec le Bénin et le Nigeria. En octobre, le GSIM a mené sa première attaque répertoriée dans la région septentrionale d’Agadez lors d’un affrontement avec les forces de sécurité près d’Assamakka. L’attaque, fin octobre, d’un poste de contrôle de sécurité dans le quartier de Seno à Niamey montre que le GSIM est capable de mener des attaques en exploitant les vulnérabilités des capitales sahéliennes et qu’il a établi une présence opérationnelle stable dans les environs de Niamey et de Bamako.

Ce qu’il faut surveiller en 2025

En ce début d’année 2025, le Sahel central continue de connaître des niveaux de violence élevés et persistants, avec une instabilité qui s’étend géographiquement et dont la nature évolue. Au Burkina Faso et au Mali en particulier, les forces étatiques ont répondu à l’intensification des activités des groupes djihadistes par des représailles violentes contre les civils, dans le but de dissuader la population d’apporter son soutien à ces groupes armés. Les groupes djihadistes, pour leur part, intensifient leurs efforts de communication et de prédication auprès des populations. En se présentant comme des protecteurs contre les forces étatiques, les mercenaires de Wagner et les milices pro-gouvernementales, le GSIM et l’EIGS consolident leur influence auprès de la population civile, laquelle est de plus en plus bloquée dans les zones contrôlées par les djihadistes.

Le conflit persistant au Sahel touche de plus en plus les centres urbains. Cela reflète une dynamique régionale plus large où l’urbanisation rapide et le ciblage stratégique de ces zones décuple l’impact des attaques militantes. Les attaques récentes contre les capitales Bamako et Niamey témoignent d’une vulnérabilité croissante de ces environnements urbains.15Jean-Hervé Jezequel, ‘L’attaque djihadiste du 17 septembre à Bamako : La stratégie de sécurité du Mali a-t-elle échoué ?,’ ICG, 24 septembre 2024 Le chevauchement entre les zones urbaines et rurales crée des problèmes de sécurité complexes, car les groupes militants utilisent les périphéries urbaines, moins sécurisées, comme têtes de pont. En outre, les progrès technologiques observés dans le cadre du conflit, en particulier le recours croissant à la guerre des drones et à la violence à distance par des acteurs non étatiques, constituent un risque supplémentaire pour la sécurité des populations et les infrastructures critiques.

En effet, l’utilisation de drones par des acteurs étatiques et des groupes armés non étatiques, notamment Wagner, le GSIM et le CSP-DPA,16X @MENASTREAM, 1er janvier 2024; David Baché, « Mali : les rebelles du CSP combattent désormais avec des drones », RFI, 12 septembre 2024; Benjamin Roger et Emmanuel Grynszpan, « Dans le nord du Mali, les drones ukrainiens éclaircissent l’horizon des rebelles », Le Monde, 10 octobre 2024 constitue un changement important dans un conflit caractérisé jusqu’alors par des méthodes de guérilla traditionnelles et sommaires. L’utilisation de drones commerciaux modifiés pour des opérations offensives devient de plus en plus élaborée et répandue, car les groupes djihadistes utilisent la guerre des drones non seulement pour des actions de surveillance et de reconnaissance, mais aussi pour des frappes ciblées au moyen d’explosifs acheminés par des drones, y compris des drones kamikazes. Ces techniques de guerre par drones représentent une avancée tactique majeure. Bien qu’émergentes, elles sont susceptibles d’être perfectionnées afin d’étendre la portée des opérations dans lesquelles elles sont employées. Ces nouveaux moyens techniques permettent des frappes de précision (en combinaison avec d’autres formes de violence à distance), une surveillance et un contrôle plus efficaces, ainsi que des opérations médiatiques et de propagande plus marquantes.

Les nouvelles alliances entre les Touaregs, les Toubous et d’autres rebelles aux frontières du Mali et du Niger, ainsi que la formation de coalitions entre les rebelles à l’intérieur du Niger, représentent autant de nouvelles variables dans l’équation du conflit. Bien que ces groupes aient actuellement une influence limitée par rapport à leurs homologues djihadistes, ils pourraient à terme préoccuper ou submerger les forces militaires étatiques, déjà confrontées à de multiples menaces de taille.

Les répercussions de cette instabilité régionale peuvent être observées dans les États voisins du Bénin et du Togo, où la progression des opérations du GSIM constitue une expansion délibérée et stratégique plutôt qu’un simple débordement. De la même manière, les zones frontalières entre le Niger et le Nigeria deviennent peu à peu des points névralgiques des activités du GSIM et de l’EIGS. Ces zones ont notamment servi de lieux de retraite et de refuge pour les deux groupes. Alors que le GSIM et l’EIGS exercent tous deux une influence coercitive sur les populations locales, le GSIM est susceptible de poursuivre sa campagne violente pour consolider son influence dans ces zones frontalières, en particulier dans le sud de la région de Dosso au Niger, où le groupe a revendiqué ses premières opérations en 2024. Dans le même temps, le fait que la présence de l’EIGS dans le nord-ouest du Nigéria ait été révélée fait pression sur le Nigéria et le Niger afin qu’ils prennent des mesures militaires, ce qui pourrait également provoquer une réponse de la part des militants de l’EIGS qui, tant ouvertement que clandestinement, se sont infiltrés dans la région sans grande entrave depuis au moins 2018. Le défi pour les gouvernements de la région sera de faire face à ces menaces en constante mutation afin d’éviter une plus grande déstabilisation et de protéger les populations vulnérables des violences qui continuent à se répandre sur leurs territoires.

Read More

To find out more, read our December 2024 Conflict Index results.