Coding decisions on gangs, unidentified armed groups, state forces, and more

Published on: 2 March 2023 | Last updated: 4 November 2024

Background on Violence in Brazil

The origins of criminal violence in Brazil are often attributed to the country’s rapid urbanization and the social inequalities brought with it. In the 1960s, advancements in agricultural mechanization led rural workers to move increasingly towards urban centers. By the 1970s, more than half of the Brazilian population lived in urban areas, having migrated in search of better lives and working conditions (IBGE, 2010). The disorderly expansion of cities led to the creation of shantytowns, the favelas, where high unemployment and the absence of significant state presence contributed to a rising crime rate. The needs of these marginalized communities were largely ignored by the state, and criminal groups began to profit from the lack of basic services. It was through the prison system, however, that criminal groups truly began to organize. First, as a means of protection against fellow inmates, and then, to establish groups that could open a dialogue with the authorities and demand better living conditions.

Economic and external factors also played an essential role in the growth of criminal violence in Brazil. The economic deadlock that affected Latin American countries in the 1980s, coupled with the oil crisis and the global cocaine boom, created ideal circumstances for the growth of a criminal market. Drug trafficking became highly lucrative, fueling the rise of organized crime in Brazil. Unregulated by law, their business grew increasingly dominated by violence.

An inadequate focus on public security policy, especially during the military dictatorship from 1964-1985, further cultivated an ideal environment for the spread of criminal violence. Criminal groups also learned effective tactics from now defunct left-wing guerrilla organizations that fought the authoritarian regime and whose shared prison experience led them to perceive convicted felons as potential allies (InsightCrime, 18 May 2018). Currently, one of the most well-organized groups in Brazil, the Red Command (CV), was formed within this context in the prison system of Rio de Janeiro. The country’s largest criminal organization, the First Capital Command (PCC), can trace its origins to similar circumstances, having emerged in São Paulo’s prison system in the 1990s following the killing of 111 prisoners by military police on 2 October 1992 (Folha de São Paulo, 2 October 2017).

These two organizations continue to operate extensively both inside and outside the prison system. Their presence is felt throughout the country, with many regional and local subsidiary factions operating as part of the larger group. They now compete with several other criminal organizations for territorial control of marginalized urban communities, as well as drug and arms trafficking routes.

The state’s failure to curb the rise of drug trafficking gangs soon paved the way for the formation of opposing vigilante groups. The police militia (milícias) groups of Rio de Janeiro state were created by former and serving police and military officers under the banner of fighting drug trafficking activities. Now present in several states of Brazil, they have extended their domain to the illegal provision of basic services and the collection of security fees. Violence perpetrated by narco gangs and police militias has become nearly indistinguishable, as both groups engage in corruption, extortion, and extrajudicial killing (The Guardian, 12 July 2018). The semi-recent development of narcomilícias – police militias operating drug selling points – further adds to the already complex landscape of criminal violence in Brazil (O Globo, 10 October 2019).

Important security improvements have been implemented in the past few years, leading to a decrease in the overall number of murders across the country (G1, 16 December 2019). However, a lack of coordinated national public security policies continues to undermine the fight against criminality. Root causes of drug trafficking – such as overcrowded prisons and poverty – remain unaddressed. Instead, past and present administrations have invested in a militarized approach to crime reduction, encouraging excessive use of force by state authorities and frequent patrols aimed at instilling fear. State forces often arrest small-scale drug traffickers without warrants and send them to prisons where they are co-opted into established groups, such as the PCC and CV, exacerbating the problem. An increase in incarceration rates during the 2000s, and the transfer of detainees between states, resulted in the expansion of criminal factions across the country, especially to the northern and northeastern regions where new coalitions emerged (INSPER, 2018).

Impacts on ACLED Methodological Decisions

Disorder in Brazil presents unique methodological challenges for ACLED coverage. These primarily concern the complex nature of Brazil’s conflict landscape, which involves continuously evolving groups and alliances incorporating both state and criminal actors. Additionally, large urban areas remain under the control of armed groups, limiting safe access to traditional journalists. As a result, much of ACLED’s Brazil data lack specific details regarding actors and motivations. ACLED has addressed these deficiencies through an increased reliance on external qualitative analysis and expertise, as well as through coverage of citizen-led journalism.

How does ACLED code certain actors in Brazil?

Brazil is amongst the few countries in which ACLED has chosen to capture certain forms of criminal violence because of their impact on territorial control and the stability of the state (for more information on this point, see ACLED’s methodology primer on gang-related violence). As a result, there are a number of unique and important general actors present in the Brazilian data that should be noted.

Security Forces of Brazil

Because of the specificity used by regional sources in regards to the identity of state forces, Brazilian security forces are subdivided into a number of different units – among them federal, state, and municipal entities. Below is a table noting the different state actors used, as well as to which groups they refer.

| Actor Name | Includes the following groups: |

|---|---|

| Military Forces of Brazil |

|

| Military Forces of Brazil – Military Police |

This is the default actor for all events where “police” are involved in armed confrontations in the slums (favelas). |

| Military Forces of Brazil – UPP: Pacifying Police Unit |

|

| Police Forces of Brazil |

This is the general police actor when no other information is given. |

| Police Forces of Brazil – Civil Police |

This is the default actor for all events where reports note more generally that “police” are involved in operations related to investigations. |

| Police Forces of Brazil – Federal Police |

|

| Police Forces of Brazil – Prison Guards |

|

Drug Trafficking Groups, Militia Groups, and Unidentified Armed Groups

In Brazil, as in many other Latin American countries, the reporting of violence by criminal or other armed groups often does not include the identity of the specific groups involved. As a result, the majority of violent events in ACLED’s Brazil data use more generic actor names to describe these groups based on certain variables present in the source material. There are two main types of non-state armed groups that operate in Brazil: drug trafficking groups, and local armed groups referred to as police militias (milícias).

Specific drug trafficking groups are occasionally mentioned by name, and are coded as such. In these cases, the most popular name of the group is used, including well-known acronyms where applicable (e.g. PCC: First Capital, CV: Red Command). In most cases, however, sources use broader descriptors, such as drug trafficking group, criminal organization/faction (facção), etc. For these cases, it is important to keep in mind that drug trafficking groups are typically affiliated with larger national or transnational criminal groups (such as those previously named). As such, when these general terms linking a group to drug trafficking or organized crime are used by a source, the primary actor is coded as Unidentified Gang, with an interaction code of ‘Political Militias’ (3), per ACLED methodology.

Clandestine police militias hold more power than drug trafficking groups because they are organized primarily by current or former public agents and, therefore, have access to powerful positions within the state. They were initially formed as a way to ‘protect’ citizens from drug trafficking groups through the use of vigilante violence, and this is how they justify their legitimacy. However, their methods are coercive, and they charge a ‘tax’ from residents in return for protection. Lately, these groups have become more violent and may begin to pose a larger threat to civilians than drug trafficking groups in Rio de Janeiro (Financial Times, 25 March 2019). A 2008 Congressional Investigative Commission defined the key characteristics of militia groups in Brazil, one of which being that they are opposed to drug trafficking.1a) Territorial domination; b) an active participation of state public agents in position of command; c) coercion against residents and merchants; d) motivated by individual profit; and e) their narrative to justify their legitimacy is that they intend to liberate people from the drug trafficking groups and establish a protective order within the communities (NEPP-DH, 2008).

However, according to a report from the Rio de Janeiro Public Prosecutor Office, as of October 2019, more than 180 localities in the State of Rio de Janeiro are controlled by so-called narcomílicias (O Globo, 10 October 2019). In these areas, the illegal exploitation of services and the collection of security fees – typical activities of police militias – are often accompanied by agreements with local trafficking and criminal groups and the control of drug selling points.2 Therefore, for all municipalities in the state of Rio de Janeiro, the Unidentified Gang and/or Police Militia primary actor is used even in situations where normally gang-qualifying terms such as organized crime/drug trafficking/criminal factions are reported by the source. This is valid for 2018 onward, as there is evidence that these groups have been active for many years. As is the case with drug trafficking groups, police militias will sometimes be mentioned in the source by name –such as the Liga da Justica and Chico Bala. However, most of the time a source will refer to these groups simply as milícia or miliciano. Therefore, the more general Police Militia actor is used when a source refers to a group as either a milícia, or there is reference to former or standing public agents acting within a group. Police militias are coded with an interaction code of ‘Political Militias’ (3), per ACLED methodology.

In other instances, the source material may be lacking even further in detail. Two actors may be coded in such cases, depending on the information available. The Unidentified Armed Group actor is used in such cases when an event involves an armed group or member of an armed group along with sophisticated weapons (e.g. firearms, explosives, etc.),3 Under certain circumstances, the presence of sophisticated weapons is implied by the source rather than specified, such as when a group simply ‘clashes’ with police; these would be included. Further, non-lethal events such as abductions may also be included without specific reference to sophisticated weaponry. and/or when a political actor is targeted (e.g. a politician, judge, etc.). Such instances include simple “shootouts reported” in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, where there is no information on the actors involved besides that they are both armed. Similarly, the Unidentified Gang and/or Police Militia actor is used under the same circumstances as above, but where it is also clear that a) one of the actors is not acting in the role of an official state agent, and either b) the event is taking place within an area where both groups are likely to be active (typically urban areas), or c) there is some indication that either gangs or militias are involved (e.g. drive-by shootings, mutilations, executions, or notes at the scene). This actor will often be used in circumstances where police are battling an unidentified armed group in cities. Both criminal organizations and police militias act in similar ways and are mostly indistinguishable from each other in cases where the source does not provide additional information such as the names of the groups, the presence of drugs (outside of Rio de Janeiro), or other identifying features. Both actors are coded with an interaction code of ‘Political Militias’ (3), per ACLED methodology.

How are locations coded in Brazil?

ACLED provides up to three administrative divisions for each of its country datasets. Typically, these levels are based off of official administrative boundaries. In some cases, official boundaries may not exist for higher level divisions. In other cases, ACLED may forego including higher level divisions if they are deemed to be unuseful. In Brazil, the Admin 3 distritos are essentially the same as the Locations, and are thus not included in the data. Below are the administrative divisions included in the Brazil data. Map 1 illustrates the Admin 1 state boundaries.

ADMIN 1: State (Estado)

ADMIN 2: Municipality (Municípios)

ADMIN 3: Not Applicable (ACLED does not code ADMIN 3 in Brazil)

LOCATION: A populated place (city, village, some ‘distritos’, etc.), natural landmark (hill or mountain, bay, etc.), or a distinct location outside the borders of a population center (military bases, rural airports, etc.)

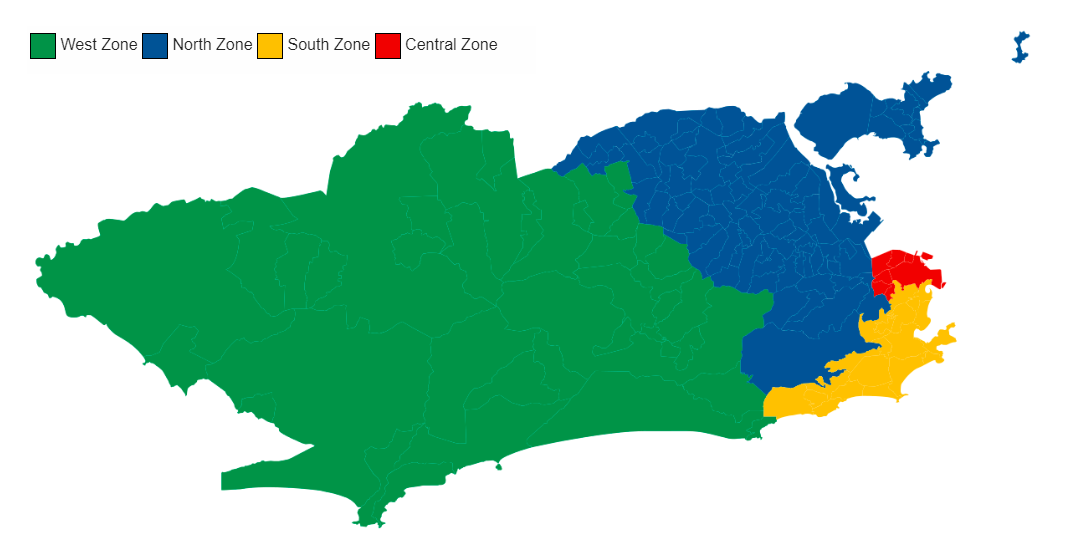

Map 1: States of Brazil 4 Map courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Are there locations in Brazil coded below the city level?

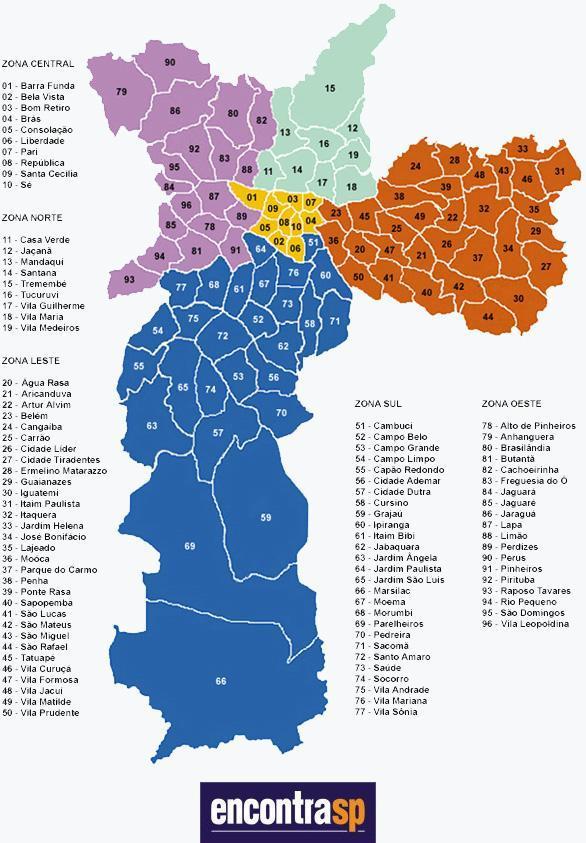

Both Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo are subdivided into their constituent administrative ‘zones’ – see maps below. The naming scheme for these Locations in the data follows the standard ACLED format of “City-Subdivision” (e.g. Rio de Janeiro-South Zone), with the administrative zone also appearing in the ADMIN 2 column. Even more specific information on lower subdivisions (burroughs, bairros, favelas) may be found within the Notes column if specified by the source.

A depiction of Rio de Janeiro can be seen in Map 2 below; São Paulo is depicted in Map 3. For the latter, in particular, ACLED has chosen to use the five zone division (see map below) over the more official nine zone division because it more closely reflects how locations are referred to in sources, many of which are ‘new media’ (more on that in the following section).

Map 2: Zones of Rio de Janeiro5 Map courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, with legend added to image

Map 3: Zones of São Paulo 6 Map courtesy of Encontra São Paulo

How are events sourced for Brazil?

Each week, ACLED researchers review over 50 English and Portuguese language sources to code political violence and demonstrations across Brazil; a further four sources are reviewed on a bi-weekly to monthly interval given that they produce reports on a more sporadic basis. Similar to many other countries within Latin America, journalists face a hostile media environment in Brazil, and are often the targets of violence for covering issues of corruption and links between state officials and organized crime (Reporters Without Borders, 2019). These issues are compounded by the danger journalists face when attempting to access areas under the control of criminal or police militia factions within large urban centers, like in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. The natural and cultural diversity of Brazil also needs to be considered when determining sources, as many states in more rural or heavily forested areas are likely to receive little to no coverage by national or international sources; citing only the latter would inevitably inject an urban bias into the data. In an attempt to mitigate these factors, ACLED’s Brazilian source list features a number of different source types that address specific challenges.

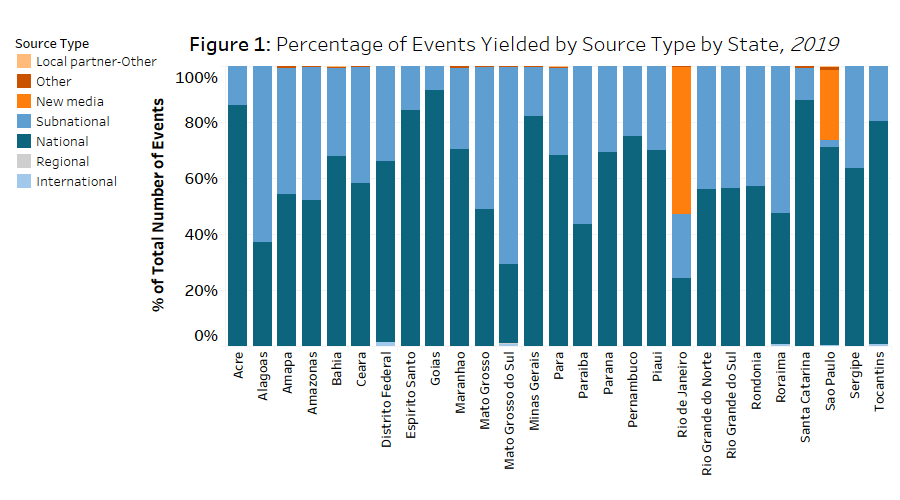

Accounting for 30% of total events, the vast majority of sources reviewed weekly are subnational, with at least one covering each of Brazil’s 26 states. Over half of events in states with smaller populations – such as Alagoas, Matto Grosso do Sul, Paraiba, and Roraima – come from subnational sources (see Figure 1 below). Additionally, approximately half of all violence targeting civilians comes from subnational media. Among subnational sources, O São Gonçalo, Globo Extra, Alagoas 24 Horas, and Midiamax produce the most events on a weekly basis.

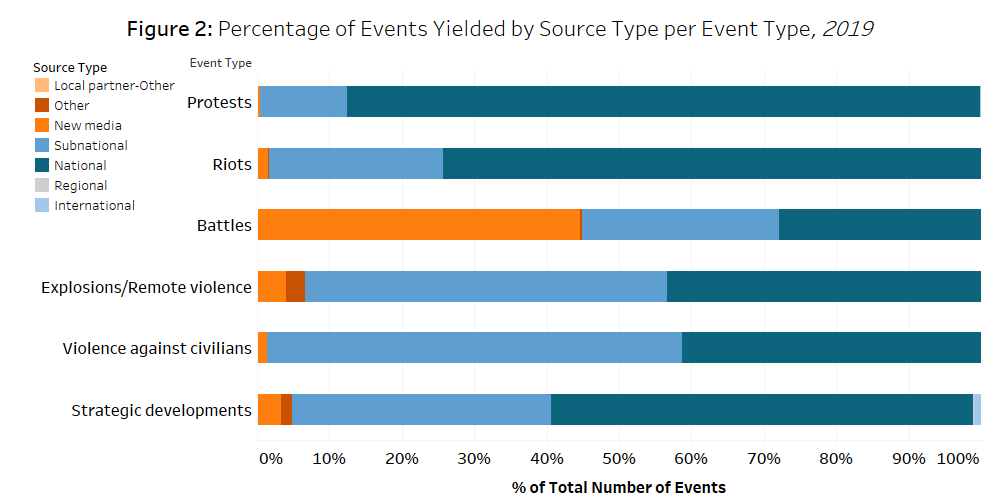

Conversely, just over half of all events in the Brazil data are sourced through six national sources: Agência Brasil, G1, Pontes Jornalismo, O Globo, R7, and Brasil de Fato. National news sources focus heavily on riots and protests, but are limited in their coverage of battles, especially in criminal and militia hotspots, such as Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo (see Figure 2 below). Other types of traditional media, such as international news agencies including Agence France Presse, Associated Press, and BBC Monitoring, are also reviewed on a weekly basis, but very rarely report unique events that are not also reported by others.

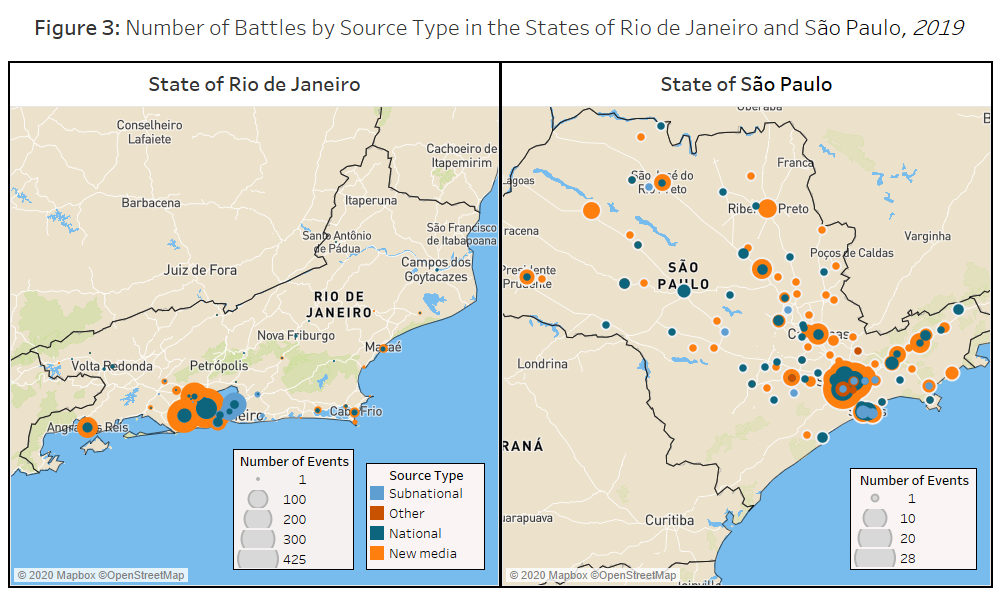

This deficiency in traditional media coverage of inter-city shootouts has given rise to citizen-led ‘new media’ solutions. The most popular of these, Onde Tem Tiroteio (OTT), is an app created to help locals in Rio de Janeiro track shootouts in real-time, thus avoiding the crossfire. OTT uses a network of trusted informants throughout the city and sends alerts of confirmed shootouts to millions of people a day via different social media platforms (Clarin, 6 July 2017). ACLED reviews OTT reports on a daily basis for both Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo states, the latter of which only began coverage in May 2018. While OTT reports are often even more vague on details than traditional media – their focus being on reporting immediate danger rather than analysis – the use of OTT as a source creates a more complete picture of violence in urban centers. In Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, 60-70% of all battles are reported through such ‘new media’ (see Figure 3 below).

Other ‘new media’ sources are also covered, mostly as a way to supplement the non-specific data received through OTT. ‘Favela News Rio de Janeiro’ is a Twitter and Facebook-based reporting network referenced by other major news sources in the country. 7 Both Estadão and R7 have referenced Favela News Rio de Janeiro media in news reports.

It often posts images and videos or provides analysis on criminal activity in the favelas, such as confrontations, territorial disputes, and the deaths of prominent drug traffickers. The ‘Crimes News RJ’ blog similarly produces images and videos of specific events within Rio de Janeiro, in addition to more in-depth analysis of factional disputes. These sources provide glimpses into the day-to-day dynamics of crime in Rio de Janeiro, which traditional reporting is unable to do as a result of security protocols. They also provide data on violence committed by state security forces themselves. Unfortunately, ACLED has yet to identify similarly reliable ‘new media’ for other regions of Brazil, although citizen reporting is on the rise.8 ‘New media’ users tend to be more prevalent in urban areas around the world (Dowd et al., 2018).

Data from OTT São Paulo is supplemented instead by occasional local law enforcement announcements through the ‘Sao Paulo State Public Safety Secretariat’ or Civil Police services – categorized under the Other source scale. The popular InSight Crime source – similarly categorized – is also reviewed on a weekly basis, and provides mostly data on strategic developments or large-scale battles between criminal groups from within prisons.

Lastly, data collected by local partners can be a powerful supplemental source. While ACLED does not yet have a local partner organization based in Brazil, data from ACLED’s global partners – Front Line Defenders and ProtectDefenders.eu – are used to supplement data on violence against human rights defenders and activists in Brazil.