Coding decisions on gangs, unidentified armed groups, self-defense groups, and more

Published on: 23 March 2023 | Last updated: 29 November 2023

Background on Violence in Mexico

The current conflict in Mexico stems from the mergence of drug trafficking and organized crime groups in the 1980s, and to this date remains fueled by demands from neighboring United States. Criminal organizations in Mexico originally emerged or were engaged as intermediaries for drug traffickers from South America as they shipped their goods through the strategic route north. Up until the late 1990s, four groups distinguished themselves as the main actors controlling specific drug trafficking zones within Mexico: the Sinaloa Cartel, the Juarez Cartel, the Cartel de Tijuana and the Gulf Cartel – respectively led by Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman Loera Guzman, Amado Carrillo Fuentes, Miguel Angel Felix Gallardo, and Juan Garcia Abrego. Despite several attempts to negotiate a peaceful partition, the growth of these groups eventually led to intense rivalries and clashes over territorial influence. These disputes became significantly more violent when the new leadership of the Gulf Cartel created an armed wing composed of former officers of the Mexican Army’s Special Forces, which later became Los Zetas. The incorporation of special forces tactics into the Gulf Cartel’s standard operating procedures changed the conflict landscape, which now involves the routine use of brutal methods of intimidation, such as beheadings and public hangings. These practices were emulated by other cartels, with rival armed wings expanding and then splintering into several new organized crime groups (e.g. La Familia Michoacana, formerly part of Los Zetas, itself formerly part of the Gulf Cartel). These splinter groups often turned against their former allies, further complicating an already complex system of partnerships and rivalries between drug trafficking groups in Mexico.

Despite years of cartel operations and increasing levels of violence, the so-called ‘War on Drugs’ was only officially declared in 2006 by President Vicente Fox, and then only seriously implemented by his successor Felipe Calderon. With state military forces sent in to dismantle the existing drug cartels rather than target the root causes of drug trafficking, former monolithic criminal groups splintered further. These actions increased the number of cartels from six to as many as 37 (El Economista, 19 May 2019). These splinter groups continue to compete over the existing drug trade infrastructure, but are also constantly evolving and diversifying their criminal activities. Mexican criminal organizations increasingly engage in kidnapping, extortion, fuel theft, and human trafficking, while operating in collusion with corrupt officials and law enforcement officers. Civilians often face the brunt of these crimes as well as the fight among rival cartels to control the criminal market (Gobierno de Mexico, December 2019).

Meanwhile, public trust in Mexico’s judicial and executive institutions is eroding due to corruption and the involvement of law enforcement agencies in extortion, drug trafficking, and human rights abuses. Consequently, many communities rely on local militia groups to ensure their safety. Community policing (policia comunitaria) is a phenomenon officially recognized in the states of Michoacán, Guerrero, Oaxaca, and San Luis Potosi, while ‘self-defense groups’ (autodefensas) and communal militias make themselves known through armed clashes with law enforcement agencies or through engaging in punitive acts against alleged criminals.

Due to the sustained nature of inter-cartel clashes and confrontation with law enforcement agents, violence in Mexico cannot be considered a mere consequence of organized criminality. The many securitization attempts led by successive administrations – the most recent being the creation of a National Guard by President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador in 2019 – are clear indications that the cartels prove to be the greatest threat to government authority, public safety, and security.

Impacts on ACLED Methodological Decisions

Disorder in Mexico presents unique methodological challenges for ACLED coverage. These primarily concern the complex nature of Mexico’s conflict landscape, which involves continuously evolving groups and alliances, as well as a dangerous media environment in which reporters face serious threats, limiting investigative journalism. As a result, much of ACLED’s Mexico data lack specific details regarding actors and motivations. These deficiencies have been addressed through an increased reliance on external qualitative analysis and expertise, as well as continued internal analysis of the data.

How does ACLED code certain actors in Mexico?

Mexico is amongst the few countries in which ACLED has chosen to capture certain criminal violence as a result of its effects on territorial control and the stability of the state (for more information on that, see ACLED’s methodology primer on gang-related violence). As a result, there are a number of unique and important actors present in the data which should be noted

Security Forces of Mexico:

Because of the specificity used by regional sources in regards to the identity of state forces, Mexican security forces are subdivided into a number of different units – among them federal, state, and municipal entities. When a source reports general “police forces,” the Police Forces of Mexico actor is used. Below is a table noting the different state actors used, as well as which groups they refer to.

|

Actor Name |

Includes the following groups: |

|

Military Forces of Mexico (2018-) |

|

|

Police Forces of Mexico (2018-) |

|

|

Police Forces of Mexico (2018-) Federal Police |

|

|

Police Forces of Mexico (2018-) Ministerial Federal Police |

|

|

Police Forces of Mexico (2018-) Prison Guards |

|

|

Police Forces of Mexico (2018-) State Police |

|

|

Police Forces of Mexico (2018-) National Guard |

|

Named and Unidentified Criminal Groups:

In Mexico, as in many other Latin American countries, the reporting of violence by criminal groups often does not include the identity of the specific groups involved. As a result, the majority of violent events in the Mexico data use more generic actor names to describe these groups based on certain variables present in the source material.

The Unidentified Gang actor is used for gang violence events where the name of the exact group is unknown in countries in which ACLED has determined that gang violence rises to the level of political violence (for more on this categorization, see this methodology primer); Mexico is categorized as one of these countries. Usage of this actor represents instances when it is reasonably clear that a gang is responsible for violence. Criteria include either the explicit mention of a gang or criminal act (e.g. drug trafficking), or one of several gang tactics, techniques, or procedures (TTPs), which have been determined based on input from country experts; such TTPs include the presence of narco-messages, public hangings, decapitation, and drive-by shootings, among others. These actors are coded with interaction code 3, per ACLED methodology.

In other instances, the source material may be lacking even further in detail. The Unidentified Armed Group actor is used in such cases when an event involves an armed group (multiple persons) and sophisticated weapons (e.g. firearms, explosives, etc.),1 Under certain circumstances, the presence of sophisticated weapons is implied by the source rather than specified, such as when a group simply ‘clashes’ with police; these would be included. Further, non-lethal events such as abductions may also be included without specific reference to sophisticated weaponry. and/or when a political actor is targeted (e.g. a politician, judge, etc.). While single person “hitmen” regularly conduct attacks on behalf of larger groups, in cases where no other indications are present the ability to distinguish these events from personal/petty disputes is nearly impossible. Events featuring attackers of an unknown number in such cases are estimated conservatively to be single and are therefore not coded by ACLED. In other cases, a source may specify that the actors engaged in violence were “individuals dressed as police” or “wearing military fatigues,” etc., implying a level of uncertainty. This uncertainty is not unfounded, as groups such as Los Zetas have been known to regularly wear police or military uniforms as disguises (Bunker, 2011). Such violence is coded by ACLED and is attributed to Unidentified Armed Groups. Unidentified Armed Groups are coded with interaction code 3, per ACLED methodology.

Where possible, ACLED codes the specific names of violent criminal organizations operating within Mexico. In these cases, the most popular name of the group is used, including well-known acronyms where applicable. Notable criminal groups include the: CJNG: Jalisco New Generation Cartel, North-East Cartel, Tepito Union Cartel, Santa Rosa de Lima Cartel, Sinaloa Cartel, Los Viagras Gang, Los Rojos Gang, Los Zetas Gang, among others.

Lastly, the Huachicoleros actor represents a specific subset of criminal groups dedicated to the theft and illicit sale of fuel. While huachicoleros are occasionally mentioned by name in a source, often the actor will be coded in events when an unidentified group is reported to be involved in the theft or illicit sale of fuel or in attacks on oil/gas pipelines. These actors are coded with interaction code 3, per ACLED methodology.

Policia Comunitaria and Self-defense Groups:

A variety of communal and vigilante militias exist in Mexico, emerging as a response to rising cartel violence in conjunction with a distrust of state forces. Among them are the policia comunitaria, as well as more general ‘self-defense groups.’ While the line between the two has become increasingly blurred, certain reports and analyses have established a distinction between policia comunitaria and self-defense groups: the former “[seek] to preserve the autonomy of indigenous peoples, allowing them to apply their own justice system,” while “self-defense groups arise in response to a public security crisis, that is, when the State has failed to protect its citizens” (Arena Publica, 29 May 2018). The policia comunitaria also theoretically maintain a high degree of organization and a strong connection with the community (which includes gun control), while self-defense forces usually do not hold a specific project or attachment to indigenous traditions; as a result they tend to weaken with time. Therefore, at least in theory, the policia comunitaria should be tied to an indigenous judicial system, often backed (or at least tolerated) by state institutions and international law; meanwhile, ‘self-defense groups’ are often financed by and/or affiliated with a cartel and usually do not hold a specific attachment to indigenous traditions. Other differences can be more nuanced. For example, some sources claim that policia comunitaria always show their faces, as opposed to self-defense groups, where armed men are frequently covered or hooded (Mirada Legislativa, 3 March 2013).

Nevertheless, in practice, all of these groups have a very similar field of action. The practical differences are very nuanced. As a result, ACLED has opted to take a conservative approach when coding communal militias in Mexico. Both policia comunitaria and self-defense groups are broader terms under which a number of groups identify. Therefore, if a source simply uses the terms ‘self-defense group’ or policia comunitaria, without mentioning a specific sub-group or any other defining features, the actor is coded as X Community Militia, with X being the region within which the group is operating. This method recognizes the complexity of defining these groups, while keeping the actors within the Identity Militia category, so that they may be analyzed separately from other types of groups. As such, these actors are coded with interaction code 4, per ACLED methodology.

Within events involving a policia comunitaria group, if the source mentions that a specific, named group is involved – in other words, officially recognized self-defense forces in Michoacán, Guerrero, Oaxaca, or San Luis Potosi, such as the Union of People and Organizations of Guerrero (UPOEG) – then the primary actor is coded as Policia Comunitaria, with the specific group as the associate actor. Such a model allows for systematic analysis of policia comunitaria groups across spaces. Using the name of the group as the primary actor name only within contexts in which this name may be known or relevant would introduce a bias into the data through suggesting different patterns of behavior.

Similarly, if a group is a known self-defense group (e.g. Comunitarios por la Paz y la Justicia; La Tecampanera), or is seemingly aligned with an organized crime group while acting as security for a community, the primary actor is coded as Self-Defense Group, with the specific group (if known) coded as the associate actor.

How are locations coded in Mexico?

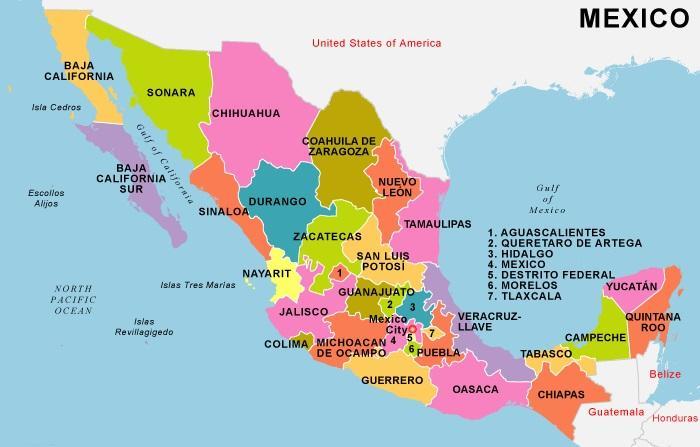

ACLED provides up to three administrative divisions for each of its country datasets. Typically, these levels are based off of official administrative boundaries. In some cases, official boundaries may not exist for higher level divisions. In other cases, ACLED may forego including higher level divisions if they are deemed to be unuseful, or make use of alternative divisions for a variety of reasons (see the Municipality footnote below). In Mexico, there are no official Admin 3 level divisions, so they are excluded. Below are the administrative divisions included in the Mexico data. Map 1 illustrates the Admin 1 state boundaries.

ADMIN 1: State (Estado)

ADMIN 2: Municipality (Municipios)

One exception to this rule exists for the state of Oaxaca, which has 570 official municipalities. ACLED has opted to instead use the 30 semi-official Districts (Distritos) as ADMIN 2 divisions, as they cover a wider area and are less likely to simply echo the data in the Location column. 2 One exception to this rule exists for the state of Oaxaca, which has 570 official municipalities. ACLED has opted to instead use the 30 semi-official Districts (Distritos) as ADMIN 2 divisions, as they cover a wider area and are less likely to simply echo the data in the Location column.

ADMIN 3: Not Applicable (there is no ADMIN 3 in Mexico)

LOCATION: A populated place (city, village, etc.), natural landmark (hill or mountain, bay, etc.), or a distinct location outside the borders of a population center (military base, some airports, etc.)

Map 1: States of Mexico 3 Map courtesy of http://www.mapsopensource.com/

Are there locations in Mexico coded below the city level?

Mexico City (Ciudad de Mexico), itself a first order administrative division, is subdivided into its 16 constituent municipalities (formerly boroughs) – see map below. The naming scheme for these Locations in the data follows the standard ACLED format of “City-Subdivision” (e.g. Ciudad de Mexico-Azcapotzalco), with the municipality also appearing in the ADMIN 2 column. Even more specific information on ‘neighborhoods’ (Colonias) may be found within the the Notes column if specified by the source (e.g. “On 9 February 2019, in Xochimilco, Distrito Federal, a male body was found hanging with hands tied and an orange rope around his neck in Colonia Ocotitla”). When sources mention that an event occured in Mexico City, yet do not specify any subdivisions, the Location is coded as Ciudad de Mexico, with Ciudad de Mexico also appearing in the ADMIN 2 column, per standard ACLED methodology.

Map 2: Municipalities of Mexico City 4 Map courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

How are events sourced for Mexico?

Each week, ACLED researchers review approximately 60 English and Spanish language sources to code political violence and demonstrations across Mexico; a further 13 sources are reviewed on a bi-weekly to monthly interval given that they produce reports on a more sporadic basis.

Though Mexico is home to a large media landscape, reporting on political violence and unrest poses a serious threat to journalists. According to the World Press Freedom Index, Mexico continues to rank as the deadliest country for reporters in Latin America (Reporters without Borders, 2019). ACLED records at least 52 instances of attacks on Mexican journalists in 2019 alone, mostly by criminal organizations. Corruption among state authorities and their entanglement with organized crime further contributes to impunity for such attacks. This, in turn, limits serious investigative journalism and fosters self-censorship when reporting on gang-related violence. It is likely that many of the issues ACLED faces in assigning specific actors to events is a result of a justified unwillingness by journalists to investigate the culprits too deeply to ensure their own safety.

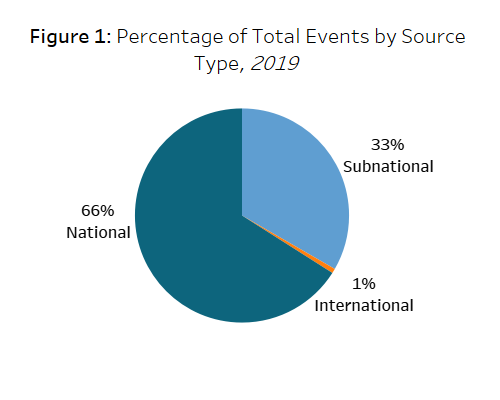

Mexico’s national media landscape is composed of several holding groups whose property is divided amongst 26 owners (Media Ownership Monitor, 2020). Half of these holdings belong to 11 families, who often have close ties to political actors. To mitigate political and editorial bias, ACLED sources from a combination of national sources belonging to at least nine different media groups. 5 These media groups are as follows: Aristegui Noticias Network – Aristegui Noticias; Comunicacion e Informacion S.A. de C.V – Proceso; Demos, Desarrollo de Medios S.A de C.V – La Jornada; Editorial Animal S. De L.R – Animal Politico; Grupo Multimedios – Milenio; Grupo Reforma – El Norte; Grupo Televisa S.A.B – SDP Noticias; Publimetro; Sin Embargo S. de R.L de C.V – Sin Embargo; Universal – El Universal. Approximately two-thirds of events are sourced through national sources such as El Universal, El Jornada, and Milenio (see Figure 1 below).

Furthermore, ACLED makes use of Mexico’s media plurality and triangulates information from national sources with subnational as well as international sources. However, international sources – consisting of news agencies such as Agence France Presse, Associated Press, and BBC Monitoring – rarely report unique events that are not also reported by others.

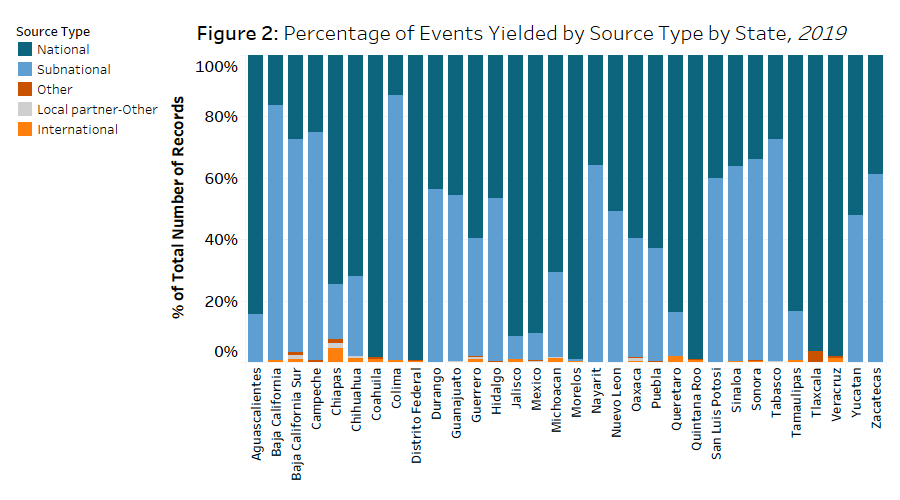

Over 30 subnational sources are referenced and help to supplement gaps in the data created by unequal coverage by national sources across Mexico’s 32 federal states. Coverage of Colima and Baja California states, for example, has benefited greatly from the subnational sources Colima Noticias as well as ‘AFN – Tijuana’ and Zeta Tijuana. These sources report on over 80% of events in their respective states (see Figure 2 below). ACLED prioritizes independent subnational sources, and endeavors, when possible, to avoid the use of sources belonging to the same media holdings as national sources it also covers.

Further supplementation, although minor, comes from reports by international monitoring groups such as Human Rights Watch, International Crisis Group, Article 19, and Insight Crime (all coded as ‘Other’ under Source Scale). Their periodical release of investigative work often improves existing data by adding new information and analysis of the evolving dynamics between criminal groups. Data gathered are also cross-checked with governmental sources when available, such as reports from the Federal Attorney General’s Office, the Interior Secretary, Mexican Government News, and Press Releases from Mexico City.

Lastly, data collected by local partners can be a powerful supplemental source. While ACLED does not yet have a local partner organization based in Mexico, data from ACLED’s global partners – Front Line Defenders and ProtectDefenders.eu – are used to supplement data on violence against human rights defenders and activists in Mexico. ACLED is also currently pursuing independent and reliable New Media sources which may provide unique events to supplement the data.