Since the upheaval of the 2008 Zimbabwean presidential elections in which much of the political violence and intimidation recorded was attributed to the Zimbabwean African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF), the level of political violence in Zimbabwe and the composition of its perpetrators has changed dramatically.

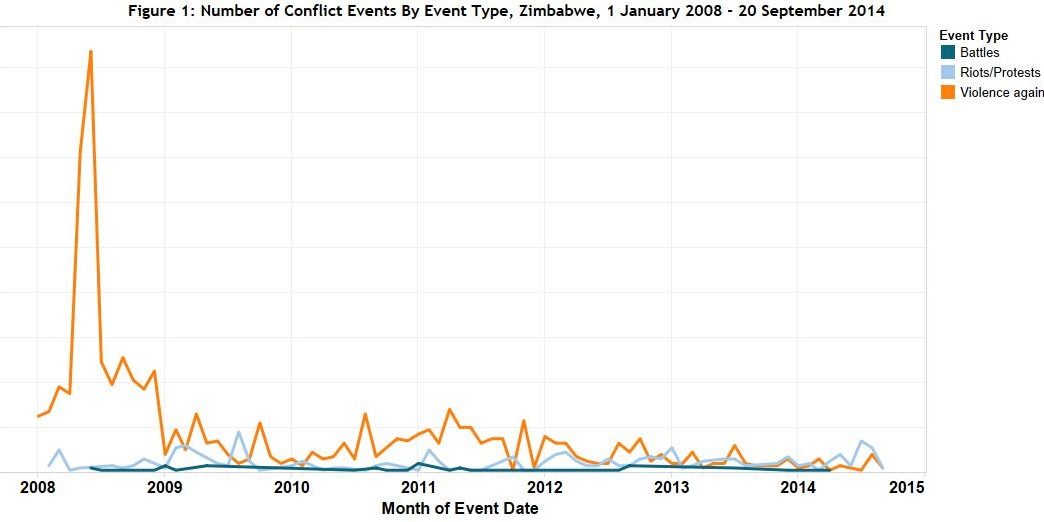

Aggregate levels of political violence have decreased dramatically since 2008. Figure 1 shows that this decrease is driven by a dramatic reduction in the incidence of violence against civilians. One potential reason for this transformation is the relative political security of ZANU-PF. Mugabe faced a severe political challenge in 2008 from the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), which mobilised trade unions, urban residents and white farmers, groups which have long opposed ZANU-PF (Booysen, 2014). However, since the MDC entered the Transitional Inclusive Government (TIG) as a partner of ZANU-PF, it has lost support. Surveys from Freedom House and Afrobarometer captured an increasing public disenchantment with the MDC after 2008 (Booysen, 2014). Although fraud is believed to have played a role in ZANU-PF’s victory in the 2013 elections, it is also believed that the MDC has lost ground among former supporters and does not pose the same political threat as it did in 2008 (Harding, 29 April 2014).

The MDC may have compromised its credibility as an opposition party and alternative to ZANU-PF by taking part in the TIG, but it has also muddied its image by engaging in factionalism and violence. Rival MDC figures Tendai Biti and Elton Mangoma suspended Tsvangirai earlier this year on the premise that the MDC needed new blood to stand a chance of dislodging ZANU-PF in the 2018 elections (Harding, 29 April 2014). Tsvangirai’s refusal to leave and attempt to rid the party of his detractors has sparked a factional battle within the MDC. This in turn has translated into violence on the street.

Figure 2 shows a significant shift in the composition of the perpetrators of violence against civilians in the last six years. In 2008, when Mugabe’s hold on power seemed tenuous, 81.84% of violent attacks against civilians were attributed to ZANU-PF, and often involved the systematic targeting of opposition supporters. However in 2014, with ZANU-PF’s recent electoral landslide and the MDC’s factional disintegration, the former’s use of political violence has decreased dramatically while MDC factions have become the primary culprit of attacks on civilians (although at a much lower absolute level than in 2008). The current targets of violence are often rivals within the MDC party.

However, ZANU-PF is itself susceptible to factionalism as various politicians within the party consider the question of who will lead after 90-year-old Mugabe vacates his post (Africa Confidential, 9 September 2014), and has in the past been linked to outbursts of violence (ACLED Conflict Trends, September 2012; June 2012). However, intra-party rivalries in ZANU-PF have typically not spilled over into systematic civilian targeting, although with uncharacteristically high rates of violence against civilians in Zimbabwe in general, whether this will become a feature of future contests remains to be seen.

References

ACLED. 2012. Conflict Trends, No. 3, June 2012, https://www.acleddata.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Trends_Report_June_2012.pdf [Last accessed: 24 September 2014].

ACLED. 2012. Conflict Trends, No. 6, September 2012, https://www.acleddata.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/ACLED_Conflict-Trends-Report-No.-6-September-2012.pdf [Last accessed: 24 September 2014].

Africa Confidential. 2014. Mice at play. Africa Confidential, 9 September 2014, 55 (18).

Booysen, Susan. 2014. The decline of Zimbabwe’s Movement for Democratic Change-Tsvangirai: public opinion polls posting the writing on the wall. Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa, 84, pp. 53-80.

Harding, Andrew. 2014. Zimbabwe’s opposition – a Greek tragedy. BBC News Africa, 29 April 2014, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-27210879 [Last accessed: 24 September 2014].