In the aftermath of the attack by Al Shabaab on the Westgate shopping centre in September 2013, President Uhuru Kenyatta vowed to punish the perpetrators of the attack and continue the ‘moral war’ against Al Shabaab. Kenyatta also called on Kenya’s diverse society to stand united against the attackers (Jamhuri, 22 September 2013). Yet, Al Shabaab has remained a dangerous force in Kenya in the year after the attack.

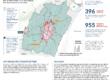

Figure 1 shows that one of the main trends in Al Shabaab activity since Westgate has been a shift in the location of attacks from being concentrated along the border areas of the north-east of the country, to the former Coast Province. The perceived marginalisation of the coastal regions and resentment of widespread landlessness among coastal populations has fuelled the formation and activity of numerous militant groups, including secessionist movements such as the Mombasa Republican Council (MRC) (IRIN, 2012). The Kenyan security services have responded to these challenges by accusing the MRC of terrorism and shutting down mosques. Critics argue that these repressive tactics have contributed to turning the region into a recruitment ground for Al Shabaab (Ramah, 10 February 2014; Daily Nation, 6 July 2014).

Similarly repressive operations have also taken place in other regions. In April, in the aftermath of an explosion in the Somali-dominated neighbourhood of Eastleigh, the Kenyan security forces launched Operation Usalama Watch. This counter-terrorist operation resulted in the large-scale arrest of Somali diaspora in Nairobi and alienated a community whose support is vital to combating Al Shabaab (International Crisis Group, 2014).

Since the death of Al Shabaab leader Ahmed Abdi Godane in Somalia on 1 September, attacks by Al Shabaab in Kenya have decreased dramatically. The last attack attributed to the group occurred in early September. It is possible that the change in leadership has forced the organisation to undergo restructuring and turn inwards. However, as Figure 2 illustrates, Al Shabaab’s activity levels have fluctuated dramatically in the past, with the organisation appearing to reduce activity or the intensity of events temporarily, and subsequently re-grouping and re-doubling efforts.

References

ACLED. 2014. Conflict Trends, No.28, July 2014 https://www.acleddata.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/ACLED-Conflict-Trends-Report-No.-28-July-2014.pdf [Last accessed: 8 October 2014].

Africa Confidential. 2014. ‘Confused response to terror attacks.’ Africa Confidential, 27 June 2014 55(13).

Daily Nation. 2014. ‘Police blame MRC for attacks in Lamu, Tana Delta.’ Daily Nation, 6 July 2014 http://www.nation.co.ke/news/Police-blame-MRC-for-attacks-in-Lamu–Tana-Delta/-/1056/2373936/-/11retqgz/-/index.html [Last accessed: 8 October 2014].

International Crisis Group. 2014. Kenya: Al Shabaab – Closer to Home. International Crisis Group Africa Briefing 102, pp. 1-20.

IRIN. 2012. Briefing: Kenya’s Coastal Separatists: menace or martyrs. IRIN, 12 October 2012 http://www.irinnews.org/report/96630/briefing-kenya-s-coastal-separatists-menace-or-martyrs [Last accessed: 8 October 2014].

Jamhuri. 2013. President Uhuru Kenyatta Addresses Kenyans on Westgate Mall Terror Attack. Jamhuri Magazine, 22 September 2013 http://jamhurimagazine.com/index.php/kenya-president/4388-president-uhuru-kenyatta-addresses-kenyans-on-westgate-mall-terror-attack.html [Last accessed: 8 October 2014].

Ramah, Rajab. 2014. Religious leaders say that closing Mombasa mosques would fuel radicalisation. Sabahi, 10 February 2014 http://sabahionline.com/en_GB/articles/hoa/articles/features/2014/02/10/feature-01 [Last accessed: 8 October 2014].