Libya was the fourth most active and the sixth most violent country in the ACLED dataset with 2383 reported fatalities from battles and remote violence in 2014. The deterioration of security in Libya throughout 2014 has been characterized by a myriad of factional armed groups with complex competing claims and two divided governments mobilizing competing narratives in the pursuit of ‘political legitimacy’. For a country that is rich through oil revenues with a relatively homogenous population (The Economist, 10 January, 2015), how can we begin to understand the drivers of this escalatory factional violence?

The 2014 conflict has been characterized by many as an ideological battle between a largely Islamist camp led by the militia groups from Misratah, and anti-Islamist coalition between military forces under the command of ex-General Khalifa Haftar and the Zintan militia. However, given that the Libya Dawn coalition is formed by Islamist and non-Islamist groups, and multiple tribal groups are involved, this is a broad oversimplification of the nature of the conflict.

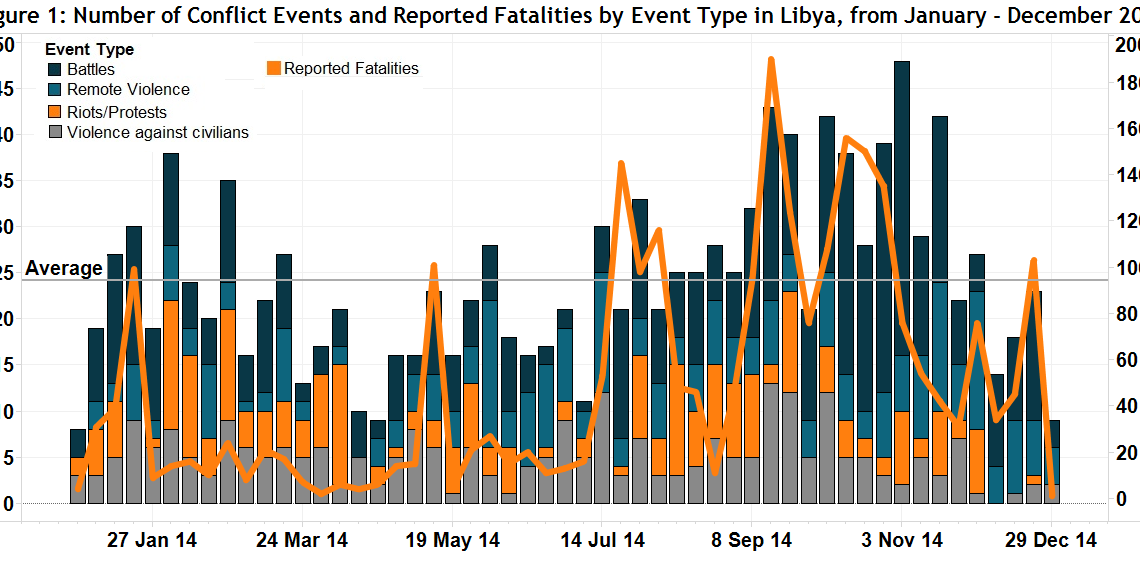

An alternative analysis of the fluidity of alliance formation in 2014 can be explained as an attempt to consolidate political positions in order to maintain leverage over the weak Libyan government. The protracted escalation of battles and remote violence (see Figure 1) over the course of 2014 can be understood by government-funded militias’ pursuit to secure resources and financial assistance from outside powers such as Egypt, the UAE, Sudan, Qatar and Turkey, as well as through informal redistributive networks by the Libyan government. This has acted as an incentive for divergent groups to prolong conflict in pursuit of material gain and political aspirations (Forbes, 6 January 2015), rather than meet at the negotiation table. From mid-May, members of the Libya Dawn coalition undertook a campaign to capture state institutions taking control of the airport and government administration in Tripoli. This was followed by attempts to divert funds from the Libyan Central Bank, a concerted effort for backing from the National Oil Corporation and in December, attacks on the oil ports of Sidra and Ra’s Lanuf.

The shift in tactics by Operation Sunrise (under the banner of Libya Dawn) to attack oil installations has added to the severe consequences facing the Libyan economy. As oil production fell to 350,000 barrels per day this week (Forbes, 6 January, 2015), the UN Special Representative for Libya, Bernadino Léon announced that the previously uncooperative warring parties agreed to a dialogue in Geneva.

The complex ‘militia rule’ is further underpinned by regional divisions. Revolutionary brigades that still operate in Libya are mobilized around city-based alliances formed during the 2011 uprising, under local municipal councils (McQuinn, 2012) (e.g. the Misratan Military Council (MMC)). Whilst armed groups were once aligned to overthrow Qaddafi, they are intrinsically tied to their local political constituencies. The upsurge in violence can be seen as an outcome of these distinct geographical units jockeying for position in a centralized political system.

AfricaAnalysisCivilians At RiskCurrent HotspotsFocus On MilitiasGovernanceIslamist ViolenceRemote ViolenceRioting And ProtestsViolence Against Civilians