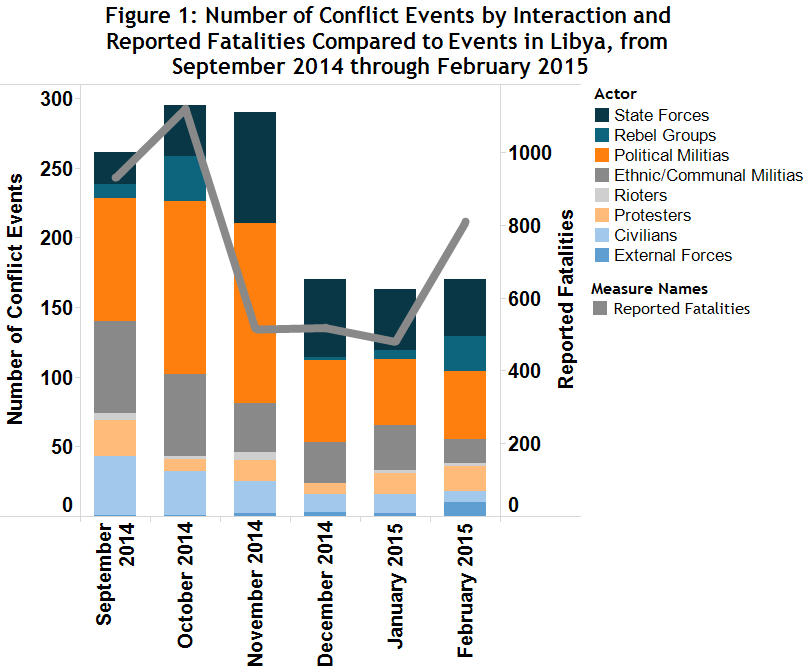

Libya was the fifth most active country in the ACLED dataset in February 2015 with an average of 4 fatalities incurred for every conflict event (see Figure 1). The recent wave of attacks by Islamic State groups has prompted widespread discussion of the role of Islamist groups such as the Shura Council of Islamic Youth, Ansar al-Sharia, Islamic State of Tripoli and the Abu Salim Martyrs Brigade in the political negotiation process mediated through the UN.

Critical to understanding their role is the historically localised nature of political contest in Libya. From this angle, current conflict dynamics and interpretations of the recent mobilisation of violent Islamist groups should not override the importance of domestic power brokerage that reflects a delicate regional distribution of power. This report highlights a case of the local contest for power between rival, co-existent Islamist groups in Derna and discusses how the shadow of ISIS in Libya, coupled with the push for a negotiated settlement, could act to preserve Misrata’s advantage.

Large-scale violent attacks and resultant casualties became more pronounced in February (see Figure 1) following the beheading of 21 Egyptian Christians, and a concerted drive to gain control of institutions in Sirte. However, groups acting under the remit of the Islamic State are not necessarily new emergent groups but nascent groups competing for recognition of power. Acting under the auspices of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi enables groups to channel resources and build up their own capacities with the goal of solidifying local dominance.

Nowhere has this been more pronounced than in the eastern city of Derna. Whilst frequently cited as being under the control of Islamic State militants, the situation on the ground appears to be more complex, reflecting intergroup tensions that are a microcosm of Libyan society at present. Following the breakdown of the Qaddafi regime, the various revolutionary, Islamist and criminal brigades that had formed in the uprising, assumed control of a number of regions. Ansar al-Sharia took de facto control of Derna.

Similarly, the Abu Salim Martyrs Brigade, a local Salafi group (Wehrey, July 12, 2012) established a security presence in the city throughout 2012 but has rejected support to ISIS; this inflamed relations with the Islamic Youth Shura Council (SCIY) who have openly declared their loyalty to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and ISIS. As “the SCIY’s decision to join the caliphate is probably an attempt to obtain religious credibility as well as funding and military tactical assistance from Islamic State…to secure full control of Derna” (IHS Janes 360, October 6, 2014) the highly localised geography of violence in Libya is key to understanding the role of ISIS.

Having addressed political forces in Derna, loose alliancebuilding by Libya Dawn may well come to a standstill in the coming weeks. Previously, they built coalitions with any group opposed to Haftar’s forces in the east. The initial attack by Libya Dawn on Tripoli International airport was spearheaded by three battalions from Misrata, who have acted as the dominant coordinating force since (McQuinn, 2014). The willingness of Libya Dawn to coalesce with multifarious armed groups against General Khalifa Haftar since May 2014 has enabled them to mount a significant military challenge; however, this appears to be undermining the support and position of Misrata as a citystate if it is to be included in any future political settlement.

Fissures have widened between Islamists in the GNC and those deriving their political legitimacy from it – Libya Dawn. Some are weary of the threat of ISIS to regional and local interests, as seen by the deployment of Misrata’s 166 Battalion to Sirte, whilst others are willing to cooperate with ISIS forces to defeat Haftar (Kadlec and Morajea, 11 February 2015).

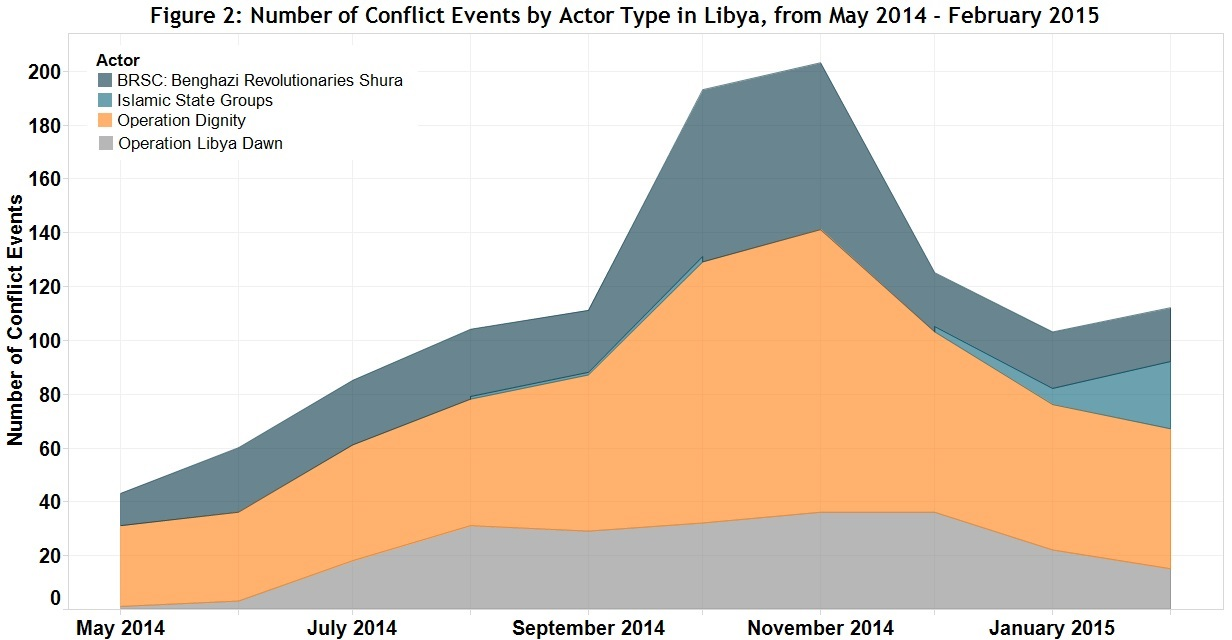

Some analysis indicates the potential for a paradigm shift in the Misratan camp to abandon the anti-Qaddafi rhetoric and to re-direct their might against regional Islamist groups that threaten localised interests. Since May 2014, in the lack of any centralised authority, groups have attempted to redefine the political landscape through an inclusive political bargain, incorporating influential forces into one broad-based coalition or another. However, Libya is on the cusp of a critical juncture in which a gradual splintering of the fluid alliances is ready to unfold if neither Dawn nor Dignity perceive they have the resources for an outright military win. Figure 2 illustrates the declining role of political and ethnic militias since November 2014. In the coming weeks, attention should be paid to the direction of violence by Libya Dawn groups to analyse whether they engage less with Dignity forces and target violent Islamist groups, thus indicating their opportunistic detachment from short-term alliances.

This may create opportunities for a negotiated settlement that would see ISIS forces and other regional Islamist actors such as Ansar al-Sharia (Derna) excluded from political negotiations. At least in the short-term this would leave the Libya Dawn coalition exposed to attacks by Haftar. But owing to Misrata’s economic and political importance, the ball may well be in Misratan’s court to determine the course of the peace negotiations if they deem it appropriate to pursue a process of balancing. Having established relative autonomy from central government by holding municipal elections in February 2012 (The Guardian, 10 June, 2012), the city boasts a well-developed business elite, industrial production and a commercial port.

Why would they pursue a negotiated settlement? Because of Misrata’s strategic and political influence– closer alignment with ISIS-leaning factions almost certainly prompt escalated discussions for international intervention that would favour the House of Representatives (HoR) whilst eroding that of Misrata. Should the Libya Dawn faction distance itself from more regional radical Islamist groups, a negotiated settlement of this nature would act to reestablish Misrata as a central powerbroker in the future of Libyan governance.

The issue is discerning the driving motive of individual groups within and across each coalition. With the highly localised competition in Derna between rival Islamist groups and the willingness of Misrata to lend support to groups opposed to Haftar, distinguishing between ‘moderate Islamist’, ‘extreme Islamist’, ‘expansionist Islamist’, ‘anti-Islamist’, ‘revolutionary’, ‘tribal’, ‘local’ and other such conflict drivers is a highly sensitive task.

AfricaAnalysisCivilians At RiskCurrent HotspotsFocus On MilitiasIslamist ViolenceRioting And ProtestsViolence Against Civilians