Sustained collective action in the lead up to, over the course of, and in the fallout from, the Arab Spring uprisings in 2011 has resulted in a rising trend of riots and protests, and an intensification in the violence witnessed across these events. The multiple social movements that emerged in the wake of 2011 have experienced different patterns of diffusion and varying mobilisation dynamics, with some countries witnessing largely nonviolent challenges to the state whilst others have escalated into more organised violent movements with multiple, competing actors. Despite adverse economic conditions, Tunisia organised a successful parliamentary election on the 23 October 2014 to lead the country towards a stable transition. Egypt’s attempt to establish a representative leader has created a protracted protest movement and a remote insurgency in the Sinai Peninsula, whilst Libya’s initial civic uprising rapidly evolved into an armed rebellion requiring NATO-intervention and has most recently resulted in a bifurcated political landscape where two rival parliaments backed by a complex network of political militia alliances compete for political influence.

This working paper identifies how patterns of collective action have transformed in the post-Arab Spring period in their form, intensity and emergence of key agents of change across Egypt and Libya. It explores the impact of key state policies on the behaviour of collective actors, providing a preliminary framework for understanding how non-violent anti-regime protests can escalate into more organised forms of violence. Analysing how elite-mass interactions have shifted from 2011-2015, it explores the spatial dynamics of collective action and demonstrates that changing power relations between the Muslim Brotherhood, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) and the executive have affected the geographical distribution of violence on a sub-national level in Egypt.

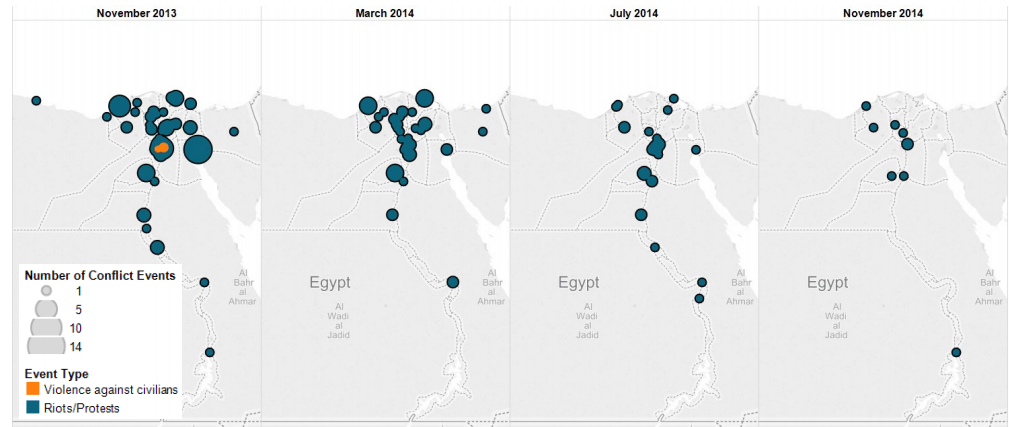

Figure 1: Number of Riots and Protests involving the Muslim Brotherhood after designation as a ‘terrorist organisation’ in Egypt, November 2013-November 2014.

The paper contends that state-dissident interactions are situated within cycles of contention that create incentives and disincentives for collective actors to escalate their demands in more violent forms of conflict. Adopting a state-society perspective of revolutions, the paper establishes that “shifts in societal interests and movements over time are often a consequence of the feedback effects from earlier policies and institutions” (Sellers, 2011: 137). It concludes by outlining two areas of further research. Firstly, the need to explore how political processes on the national and sub-national level interact, to understand the distinct geographical spaces of violence produced through mobilisation. Secondly, following della Porta’s view of “violence as escalation of action repertoires within protest cycles” (2008: 221), it calls for fresh attention towards the mechanisms and processes through which political violence escalates from a social movement perspective. Understanding the role of the state, non-state actors, and political opportunities in establishing governance practices will contribute to our knowledge on the ways in which non-violent state challenges are able to radicalise or develop into more organised, violent confrontations.

The full working paper can be found here

References

Della Porta, D. (2008) Research on Social Movements and Political Violence. Qual Sociol. Vol. 31. pp. 221-230

Sellers, J. M. (2011) Chp 9 ‘State-Society Relations’ in The Sage Handbook of Governance, edited by Bevir, M. pp.124-141.