Conflict levels fell dramatically in May 2015 after South Africa suffered a wave of xenophobic and anti-foreigner violence in April. The scale of the violence surpassed the anti-foreigner riots that hit Soweto in January 2015 after an alleged robber was shot by a Somali shopkeeper, prompting South African residents to loot foreign-owned shops. The violence resulted in multiple fatalities and resulted in over 8,000 foreign-born residents inhabiting camps for these internally displaced (Westcott, 2015). The rapidity with which the violence spread and the ferocity of the anti-foreigner sentiment exhibited by the riots has prompted analysts to examine the roots causes of xenophobic violence in South Africa.

Immediate blame has been placed upon Zulu monarch Goodwill Zwelithini kaBhekuzulu for a public proclamation made in late March demanding that foreigners should be deported to reduce competition for employment (Ndou, 2015). The blame is not without reason as KwaZulu-Natal, where the king’s authority holds most cultural influence, was the epicentre of violence and accounts for 47.6% of all violent xenophobic incidents in April and there have been reports of rioters using the king’s words to justify their actions (Ngubane, 2015). As a result, countries such as Nigeria, whose diaspora community was extensively targeted by the rioters, have sought to have the International Criminal Court indict the monarch as responsible for the violence (Scales and Sanpath, 2015).

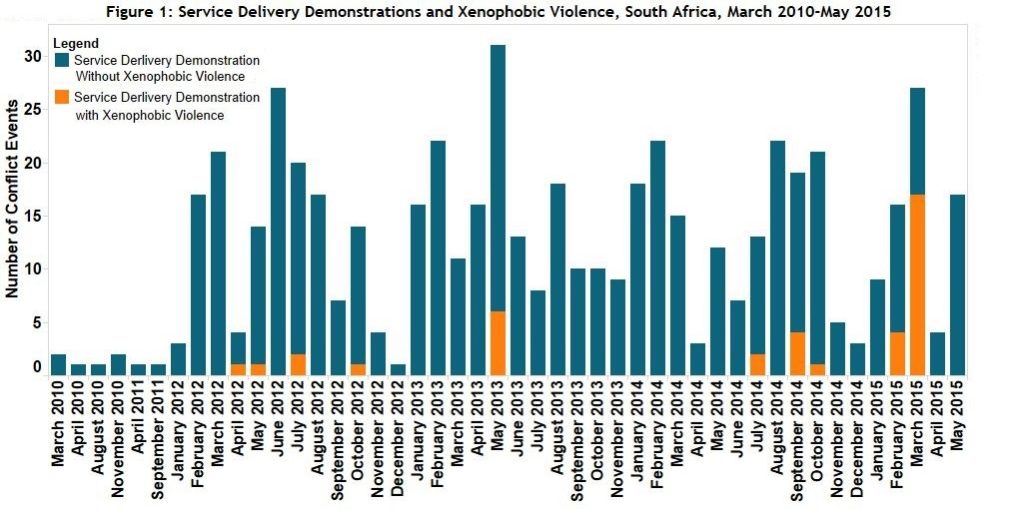

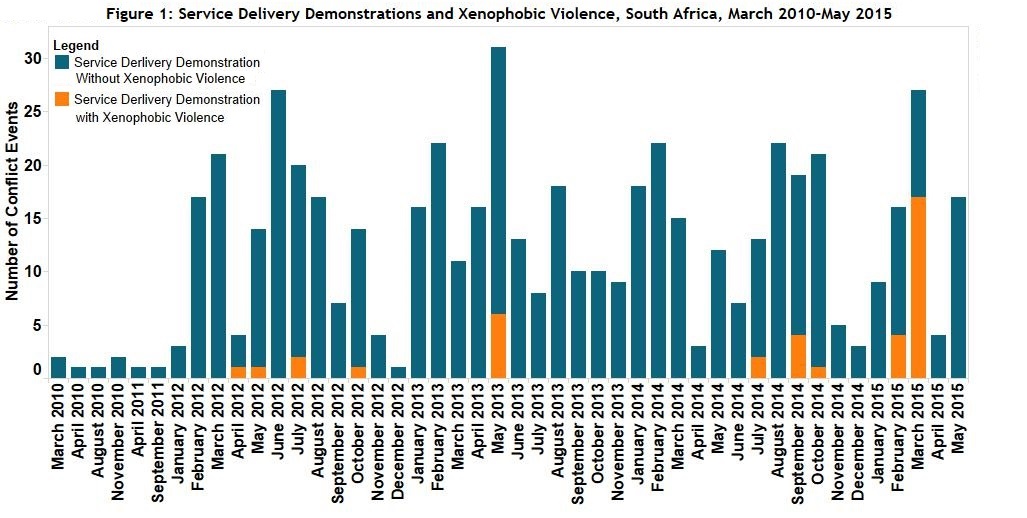

However, there has been a great deal of attention in investigating the root causes of the violence. Though unemployment has commonly been cited as a reason for violent xenophobia, the fact that the 2008 violence took place during a year of exceptionally low unemployment and that migrants only constitute 4% of the working population, both provide counter-evidence to this narrative (Anyadike, 2015; Trading Economics, 2015). Instead, there is evidence that foreigners function as scapegoats for larger government failures such as service delivery and job creation, with protests against state performance often accompanied by the looting of foreign-owned shops (Anyadike, 2015). This interpretation is supported by the data. In the run up to the April 2015 violence, service delivery demonstrations were increasingly marred by episodes of xenophobia with anti-foreigner incidents present in over half of service-related protests in March 2015 (see Figure 1).

Only a single xenophobic incident took place in May 2015, representing a marked contrast to the preceding months. This decrease may partly be driven by the surge in public anti-xenophobia sentiment by influential political actors including the ruling ANC, rival Economic Freedom Fighters and Democratic Alliance parties, and numerous student organisations. These protests have informed the perpetrators of xenophobic violence that the migrant status of their victims does not mean that their crimes are condoned or ignored by the public or the political elite. This has eliminated the culture of impunity concerning xenophobic violence that has prevailed in South Africa since the 2008 violence resulted in only 79 convictions (Rabkin, 2015).

AfricaAnalysisCivilians At RiskHuman RightsInequalityLocal-Level ViolenceUnidentified Armed GroupsViolence Against Civilians