By the end of the 10th of June by-elections, the ruling Zimbabwean African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) had won all 16 contested constituencies. In the run up to the contest, the by-elections had pitted current ZANU-PF insiders against party exiles who had been purged for their alleged connections to ex-Vice President Joice Mjuru. Ex-ZANU-PF notables such as Temba Mliswa ran as independents against their former patrons, capitalising on their political roots within the constituencies to mount a challenge against ZANU-PF hegemony.

The by-elections had similarly raised tensions within the various factions of the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC). The decision of MDC-Tsvangirai (MDC-T) leader, Morgan Tsvangirai to have 21 legislators expelled for aligning with the rival MDC-Renewal (MDC-R) party weakened the MDC-T’s position within the legislature (Langa, 2015). The decision by Tsvangirai to not contest the by-elections ensured that the MDC-T’s weakened position would remain solidified until the 2018 general election. This decision led to a violent rift within MDC-T between members who support Tsvangirai’s decision to boycott the polls and those aligned with MDC-T deputy, Thokozani Khupe, who opposes the boycott (Chidza, 26 May 2015).

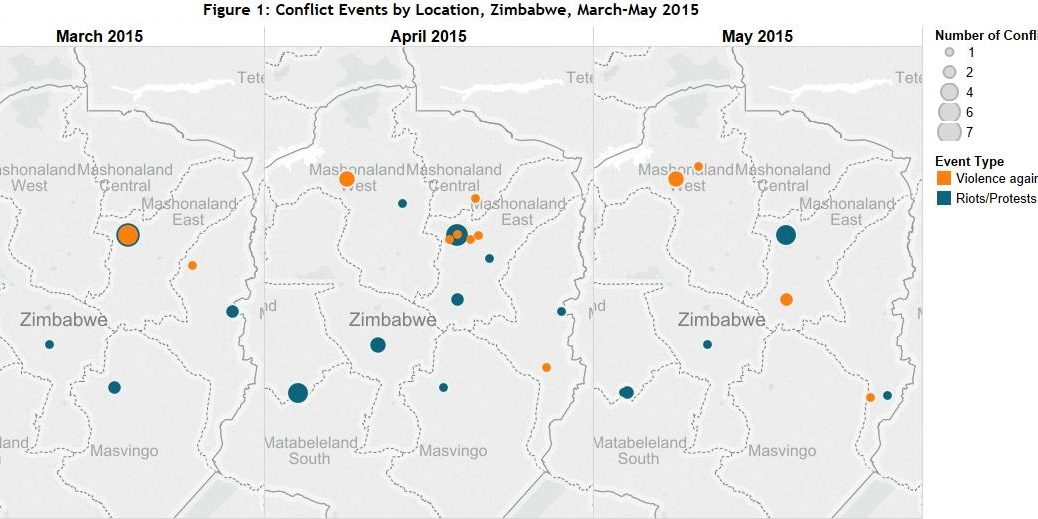

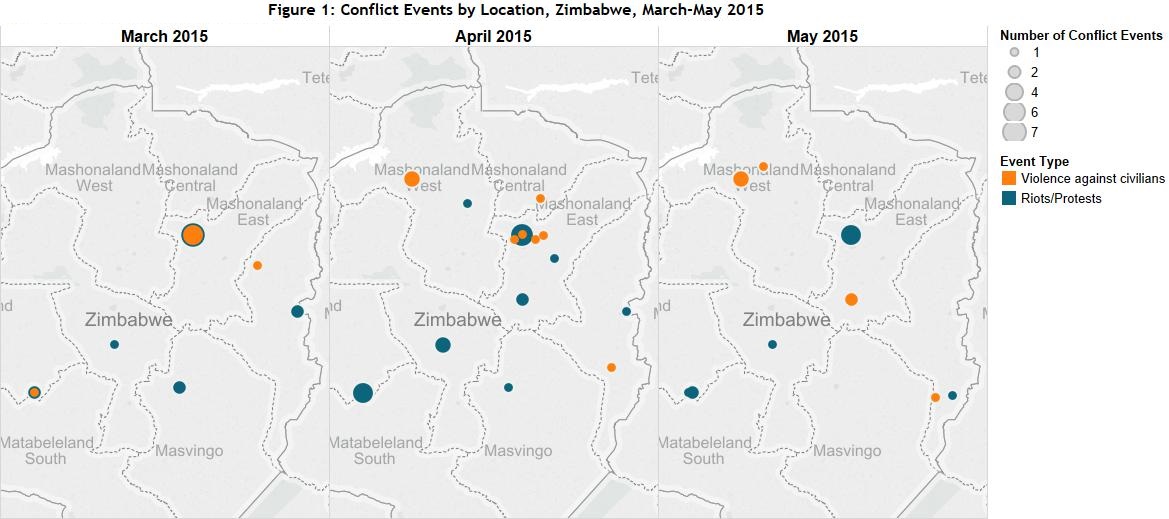

The run up to the by-elections were marked by violence against voters by ZANU-PF youth, especially in areas such as Hurungwe West in Mashonaland West, where independent candidates posed a credible threat to the ruling party (see Figure 1). In April, the issue of the MDC-T boycott provoked a violent clash between the Tsvangirai and Khupe factions of the party in Bulawayo.

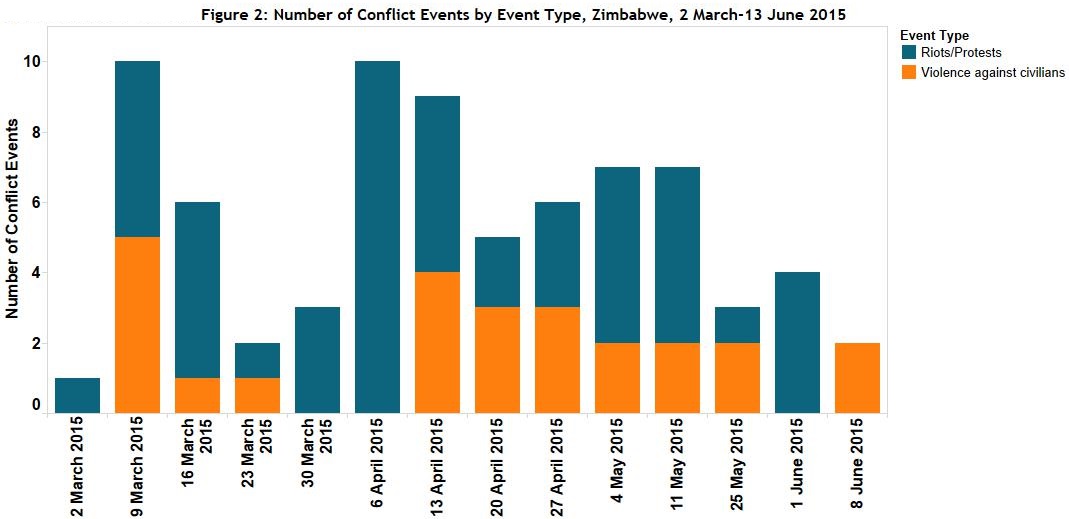

However, in spite of high levels of political violence in the run up to the election, the by-election itself was marked by a distinct lack of overt conflict or violence (see Figure 2). The week of the by-election had the lowest levels of violence since mid-March. Though surprising, this lack of violence is indicative of ZANU-PF’s tactics in the post-2008 era. Subtle forms of intimidation or disenfranchisement, such as noting down the names of voters, excluding names from voter rolls and the threat of arrest, have replaced the mass violence that characterised the 2008 runoff election (The Zimbabwean, 10 June 2015). The precedent set in 2008 and, to a lesser degree, earlier this year means that the ever-present possibility of anti-opposition violence is all that is needed to stifle dissent.

Other factors such as voter apathy and the MDC-T boycott further reduced the need for violence as the electorate opposed to the regime increasingly sees elections as a futile mechanism for change (Kunambura, 11 June 2015). Though this apathy may empower ZANU-PF in the short term, the party may face a bigger challenge in the long term. As purges and intra-party competition continue to destabilise the ZANU-PF, dissidents, opposition politicians and former insiders may resort to non-democratic means to dislodge the regime.

.

AfricaAnalysisCivilians At RiskElectionsLocal-Level ViolencePolitical StabilityRioting And ProtestsViolence Against Civilians