Zimbabwe’s political violence is characterized by several distinct features. An extremely high proportion of all conflict is directed against civilians: while across Africa, violence against civilians’ averages at 30% of total political violence, in Zimbabwe, it accounts for 75% as an average from 1997-2015.Most violent acts are perpetrated by political militias associated with the Mugabe regime and the ZANU political party and a high proportion of the acts are sanctioned, condoned and supported by the state security mechanisms and occur during times of high volatility and political threat. Peaks and lulls frequently reoccur, but differ in their intensity. Crises occurred during multi-party elections in 2002 and 2008 and in the street protests in 2003, but since the 2013 elections, violence is increasingly contained within parties. For this reason, the stability and power dynamics within the ruling ZANU party will likely shape present and future violence patterns, locations and intensity.

Competition within and across political parties in Zimbabwe has led to intense bouts of ‘eliminationist’ violence. This form involves competitors from local to national scales engaging in violence to limit opposition, secure dominant positions and capture rent seeking opportunities. This form is in contrast to ‘bargaining’ violence (De Waal, 2009) and ‘symbiotic’ violence (such as that which occurs in DR-Congo, Somalia and Nigeria). In Zimbabwe, political elimination is primarily pursued through attacking supporters of opposition parties and community mobilisers. In the recent past, potential supporters of the opposition political organizations have largely been targeted.

Militias supported and mobilized by political elite and state security forces are responsible for the vast majority of violence against civilians and clashes between parties. Multiple militia groups have emerged both within the dominant ZANU power structure and the MDC opposition. Militias are a frequent perpetrator of violence in Zimbabwe as they operate as armed wings for politicians or factions within parties, and allow political elites to simultaneously deny responsibility for violence and benefit from its consequences.

Recent patterns indicate a change to the dynamics of Zimbabwe violence, but not its motive. From 2012 to the recent 2015 by-elections, violence against civilians has decreased to 35% of total occurrences, and the majority of those acts still targeted MDC supporters, or supposed supporters[1] and the political affiliations of civilians. ZANU-PF groups are responsible for three times the rate of violence against civilians compared to MDC and its splinters. In turn, riots and protests now account for the most political acts[2]. Of protests that are attributed to a specific group, both MDC and ZANU-PF are equal in their activity[3]. Protesting frequently turn violent (and hence are classified as riots) when ZANU and related parties initiate such actions. ZANU’s protests are twice as likely as any other group to turn violent. Finally, in the past three years, a small number of clashes occurred within the MDC movement and its splinters. This is higher than other groups, including ZANU-PF.

How is political violence in Zimbabwe is closely linked to political competition dynamics from the local to national scales? Zimbabwe’s political violence manifests from political dynamics within and across political organizations, but mainly has emerged in line with ZANU-PF internal dynamics. At various points in the past twenty years, the Mugabe regime has been both sufficient politically dominant to shape and determine domestic political actions to its benefit, but also relatively weak at other points and requiring of interventions to limit the opposition and hold onto power. At present, the Mugabe regime is in a powerful position, secure enough to engage in a series of high level purges in order to ensure that the succession contest will be limited to persons that President Mugabe has selected, and Vice President Mnangagwa believes possible to co-opt. But multiple political scenarios are possible, and each of which create the potential for intra-party competition violence. However, VP Mnangagwa currently does not enjoy a popular mandate and his ascension to the role of President will be dependent on his ability to protect his selected elite and fend off competitors, particularly as the economy continues to shrink.

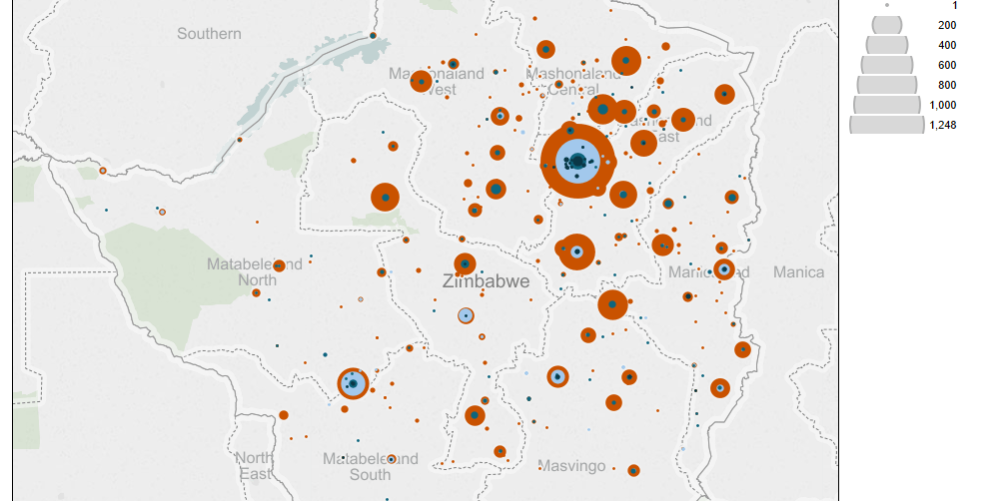

The ACLED Tableau Public storyboard on political violence in Zimbabwe can be accessed here.

[1] Almost 50% of all reported violence against civilians includes a reference to identified MDC supporters. The remaining reports often do not specify

[2] Riots are defined as violent, spontaneous acts typically instigated by civilians; protests are non-violent, spontaneous acts.

[3] Fewer than half of protests are ‘unattributed’, and of those that are attributed to a specific group, WOZA (Woman of Zimbabwe Arise) is the group that has been most targeted by police forces when protesting.

AfricaCivilians At RiskCurrent HotspotsElectionsLocal-Level ViolencePolitical StabilityRioting And ProtestsViolence Against Civilians