ACLED Asia Data from January 1st to May 31st 2015 are available for download here, and are publicly available at https://www.strausscenter.org/strauss-articles/acled-3.html. The latest ACLED Asia Conflict Trends Report offering analysis of the latest data can be accessed here.

We will continue to backdate our available data from 2010 for all countries, and will release country datasets as they become available. Pakistan will be our first completed coded country, followed by India and intermittently smaller and less active states.

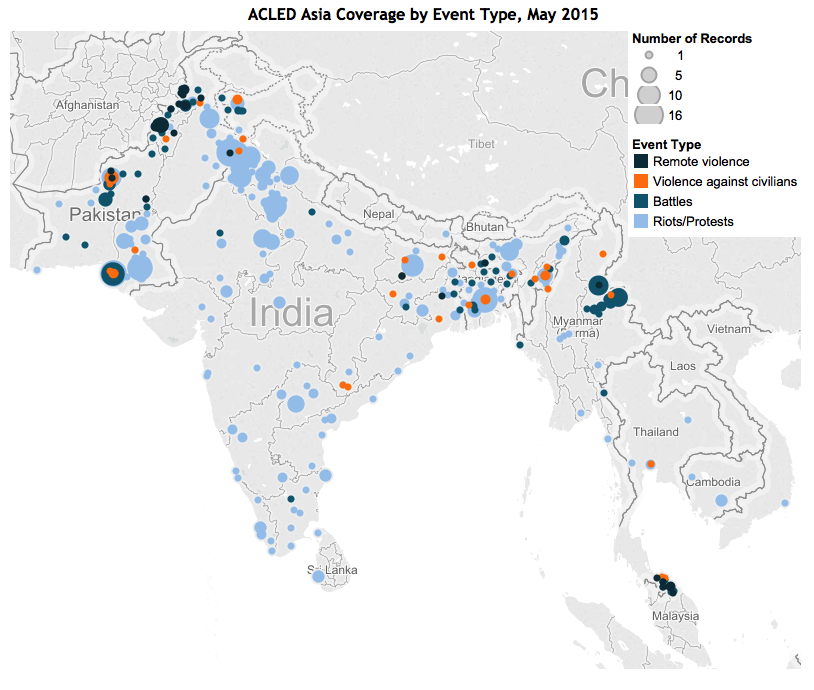

Since the previous report, ACLED-Asia has recorded a decrease in politically violent events throughout the subcontinent and Southeast Asia. The decline in active politically violent events in Bangladesh has largely driven this decrease, as an active hartal called in the latter part of December 2014, ceased in March.

ACLED incorporates reporting on non-violent protesting into these counts by country and month; these events constitute the vast majority of reported events within South Asia, particularly.

The volatility in South Asia, and the decline from an approximate average of over one thousand aggregated events to 700 in April and May, is not solely due to Bangladesh’s hartal, but is specific to the decrease in protests in India, which has recorded highs of 90 protests per week during the past and an average of 295. Pakistan, with the second highest number of protests, has generally volatile patterns running throughout the past months.

The changes in other event types also demonstrate the intense nature of campaigns in South Asia, as well as the generally low rate of significant battles and violence against civilians episodes outside of key unstable states including Pakistan and, intermittently, Myanmar. Along with riots and protests, violence against civilians declined significantly as Bangladesh’s hartal ended in mid-March. All other states register low, and persistent, levels of violence against civilians.

However, fatality levels are not decreasing in the same way as events. Fatality numbers are generally driven by Pakistan and Myanmar, and illustrate ‘campaign’ behavior in that sharp peaks and troughs are noted at key points throughout the period. Both countries are in a ‘rising’ or initial phase of a campaign during May, resulting in increased deaths.

The situations in individual states are covered throughout the trend report: the social and political upheaval due to changes in provisions regarding land acquisition by private companies suggests that the Bangladesh National Party (BNP) may be moving too swiftly towards neoliberal reforms; a review of the hartal in Bangladesh and the roots of this conflict between political parties is considered. Further, the short and long term consequences of the months-long hartal are discussed, including a lack of governmental control in rural areas, which experienced an increased number of land grabbing incidents and violent clashes of communal groups for the establishment of supremacy in rural areas. Finally, the derailing peace agreement in Myanmar is discussed, and the agendas and options for the existing parties in the conflict.

The situation in both Bangladesh and Myanmar suggest that while the ‘big’ stories demand attention, the smaller changes in political power should be acknowledged. Conflict actors- including the government, political parties, political elites, local and customary authorities- often use the veil of national or large regional conflicts to forward agendas that might otherwise be difficult to pursue, including land grabbing, personal profit, and changes in leadership structures. Local cleavages are often unreported, or under-acknowledged. Yet these fissures within rural and urban societies form the basis upon which larger contests are organized.

Other states covered by ACLED-Asia display far less violence generally, but are subject to periods of intense increases due to political unrest (e.g. Thailand, Sri Lanka, Nepal). However, during periods where an alternative instability is active, such as earthquakes that devastated Nepal in recent weeks, both incidents and reporting of political violence typically cease. Previous to the earthquake, Nepal had experienced a consistent level of protests, largely around the constitution writing process. These, and other demonstrations related to public goods access, political participation and justice, become secondary concerns during the difficult phase of grieving and rebuilding taking place in the state.