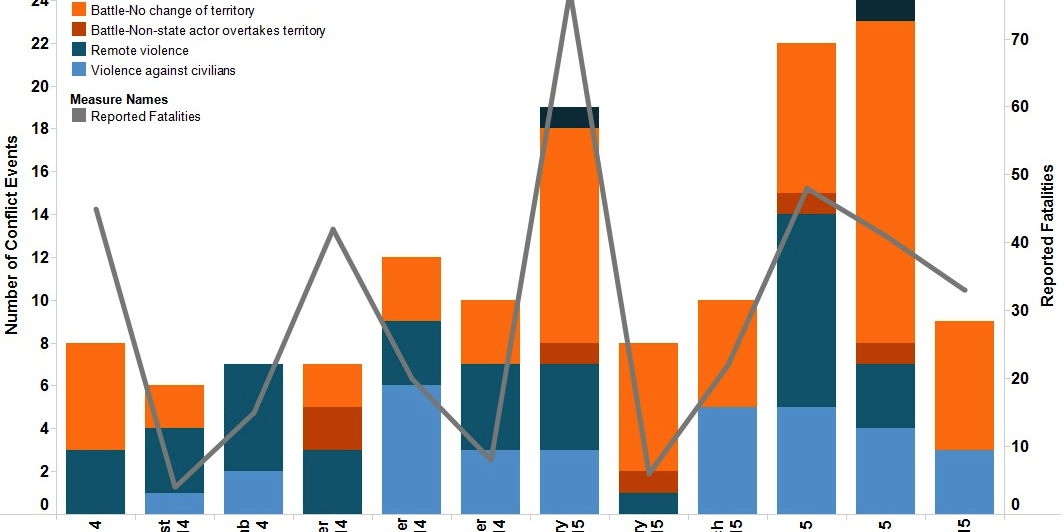

Mali’s current outlook can be termed as cautiously optimistic, although significant challenges remain following the signing of a peace treaty between the Government of Mali and representatives of the Tuareg-led rebels from the Coordination of Movements of Azawad (CMA) on June 20 (Al Jazeera, June 21, 2015). During the month the peace treaty was signed, the number of violent events and reported fatalities tracked by ACLED was significantly lower than April and May (see Figure 1), and there were no recorded instances of fighting between forces aligned with the Government of Mali and those of the CMA. Even more positively, in the run-up to the signing of the treaty, the pro-government Imghad Tuareg and Allies Self-Defense Group (GATIA) vacated the town of Menaka, allowing the Malian military and MINUSMA forces to take control and remove a major obstacle to a deal (Al Jazeera, June 19, 2015).

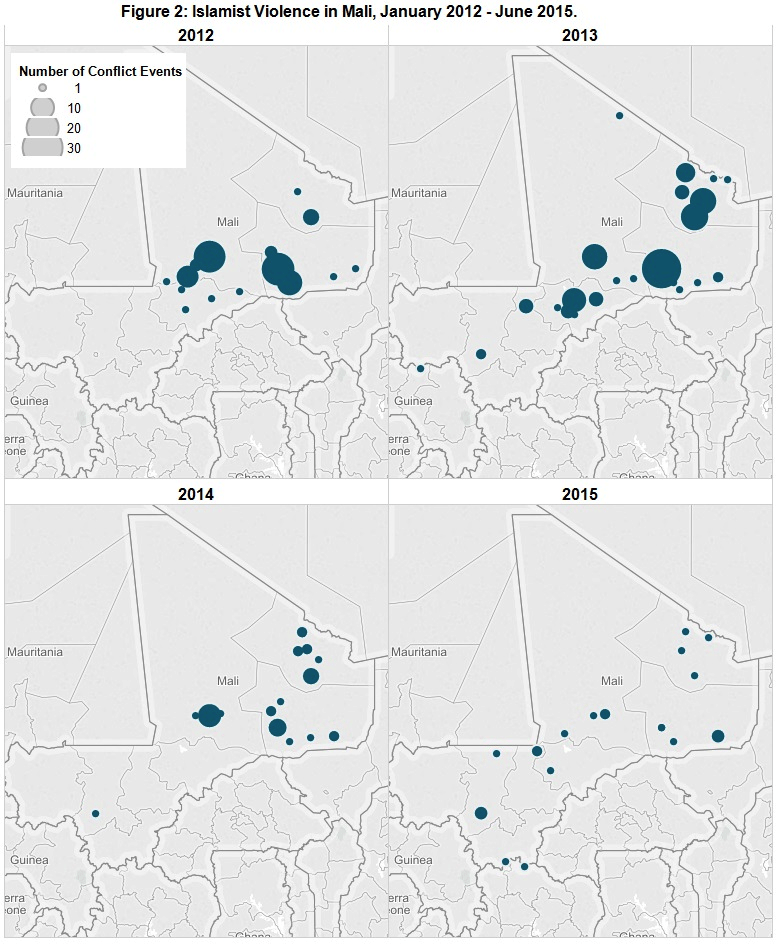

However, despite these positive signs, both the violence of the past few months and the peace treaty itself could present obstacles for future stability. Mali now faces two specific challenges: first and foremost, is the level of Islamist militant activity throughout the country, including in Bamako and areas which had not previously seen operations by these groups (see Figure 2). While the levels and intensity of this violence does not rival the peak of the Islamist-led insurgency in 2012/2013, the distribution of this violence across the country is now much more widespread than when it was primarily concentrated in the northern regions. This suggests that despite a nominal end to the rebellion, violence carried out by these groups is likely to continue and potentially expand due to their growing confidence and operational capacity. A second issue is that gaps still remain within the treaty between the government of Mali and the Tuareg-led rebels in terms of the lack of recognition for territory the CMA calls Azawad (Al Jazeera, June 17, 2015). Associated with this issue is the concern over how much control both sides have over their forces. If this control is not absolute, then fighting could again break out as it did in May 2014 when the Malian Prime Minister visited Kidal (May 22, 2014). All of these factors could jeopardize the nascent peace.

Notable attacks by violent Islamist groups during this period include an assault by al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) forces on a military base in Nampala on January 1, which killed 8 Malian soldiers and succeeded in taking the base for a short time (BBC News, January 5, 2015); a highly publicized shooting incident in March by Mourabitounes Group of Azawad (GMA) targeting a nightclub popular with foreigners in Bamako which killed five people (BBC News, March 7, 2015); and, most recently, an attack on a MINUSMA convoy near Timbuktu by suspected Islamist militants on July 2, which killed 5 peacekeepers (NBC News, July 2, 2015).

These attacks are representative of two trends in ongoing Islamist violence: first, it has moved out of the traditional areas of instability in northern Mali and is increasingly being seen directed against targets in the south. These events were also widely distributed, with every province of the country having seen at least one violent attack by recognized Islamist militant groups like AQIM or their affiliates since the beginning of 2015 (see Figure 2). Second, violence is targeted against foreigners, including both civilians and international forces. Events of remote violence targeting MINUSMA have been increasing, with two such events in January (AFP, January 4, 2015) and March (Reuters, May 28, 2015) claimed by MUJAO and AQIM respectively.

While the activity of Islamist militants in Mali is a major concern, the possibility of defusing the military standoff with the CMA in the North offers some relief on this front. It is yet to be seen whether the recently signed peace treaty will actually satisfy the Tuareg base. In Kidal– the only Tuareg-majority region of Mali–protests against the deal were held in the lead-up to the signing (Reuters, March 10, 2015) and some believe the leaders of their movement have sold out, due to the refusal of the Malian government to discuss self-rule and the perceived acceptance of considerable concessions by the CMA during negotiations (Al Jazeera, June 17, 2015).

The current situation thus creates a sense of foreboding about the future of the peace process, as a similar process occurred during the 2006-2008 Tuareg-led rebellion. During that conflict, the signing of a peace treaty with the government by the main Tuareg rebel group led to more radical splinter elements continuing to fight in protest over the terms of the deal. This, in turn, contributed to a significant proportional increase in violence as compared to the initial phases of the conflict, and left the door open for the rise of the kind of Islamic militancy that is seen today (ACLED, January 2015). In the current context, there may be an even greater risk of dissatisfied militants, who may feel betrayed by the rebel leadership, opting to support or even join Islamist militants in their continuing fight against the government.

This piece was originally featured in the July 2015 ACLED Conflict Trends Report.

AfricaAnalysisCivilians At RiskFocus On MilitiasIslamic StateIslamist ViolencePolitical StabilityRemote ViolenceViolence Against Civilians