The Fragile States Index (FSI), produced by The Fund for Peace, highlights pressures faced by states, identifying “when those pressures are pushing a state towards the brink of failure”, with the intent of shaping assessments of political risk by researchers and policymakers (Messner et al., 2015). The FSI is calculated for countries worldwide using an analytical platform drawing on data and information from a number of sources. A number of attributes within each state are taken into account and weighted – such as demographic pressures; economic factors; state legitimacy, human rights, and rule of law; etc. – to create an index for state fragility (The Fund for Peace, 2015).

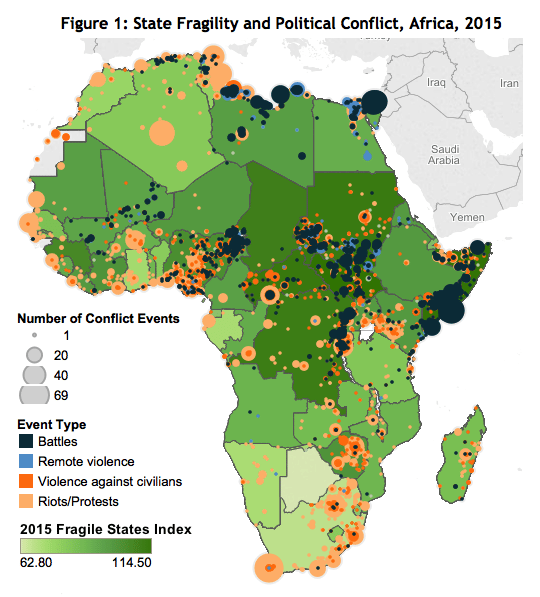

Using real-time conflict data from ACLED and the latest Fragile States Index for 2015 (based on data collected during 2014), the effect of state fragility on future conflict and violence in Africa is explored here. Figure 1 maps the geographic locations of all political conflict in Africa thus far in 2015 over a map of the 2015 state fragility scores of African states – based on levels of the various aforementioned attributes reported in 2014 – in which higher fragility scores denote higher fragility (i.e., more at risk).

In line with other studies that find correlations between state fragility and armed violence (for example, see Geiβ, 2009), states deemed on high alert with high state fragility scores – such as South Sudan, Somalia, Central African Republic, and Sudan –see some of the highest levels of conflict and violence in Africa.

However, as a result of the aggregate measures used to compile the index and their weighting, certain attributes are deemed as more or less important in contributing to state fragility. These calculations, for example, have led to South Africa being labeled as a ‘low warning’ country when it is a hotbed of social unrest with the highest number of riots and protests reported this year relative to the rest of the continent. Similarly, while North Africa is deemed not as fragile as some Sub-Saharan African states, Libya and Egypt are responsible for a large proportion of the continent’s political violence this year, reporting fatality levels approximately equivalent to Somalia and South Sudan (the two states topping the Fragile States Index). Meanwhile, Nigeria – responsible for the largest number of conflict-related deaths on the continent by far as a result of increased Boko Haram conflict activity seen this year – is deemed less fragile than countries such as Chad and Guinea; Nigeria has reported approximately 64 times as many fatalities resulting from political violence thus far this year relative to Chad and Guinea combined.

These concerns highlight the importance of not relying solely on rankings and indices when examining the fragility of states. Given the crucial role of conflict in shaping humanitarian and development agendas, it is important to acknowledge changing conflict dynamics in developing states and how state institutions (which largely dictate fragility scores) may incentivize certain conflict patterns (ACLED, 4 July 2014).

This piece was originally featured in the July 2015 ACLED Conflict Trends Report.

AfricaCivilians At RiskConflict MonitoringCurrent HotspotsData ManagementPolitical StabilityRemote ViolenceRioting And ProtestsViolence Against Civilians