In July, US President Barack Obama completed his first official visit to Kenya, which he described as a country ‘at a crossroads – a moment filled with peril, but also enormous pride’ (Obama, 2015). Security was high on the agenda for discussions, as Obama outlined ‘similar threats of terrorism’ faced by the US. Obama’s visit coincided with ongoing violence by Al Shabaab and aligned forces in Kenya, but while Al Shabaab has been active in the country for several years, and carried out multiple high-profile attacks over that time, the past few months have illustrated some emerging dynamics and shifts.

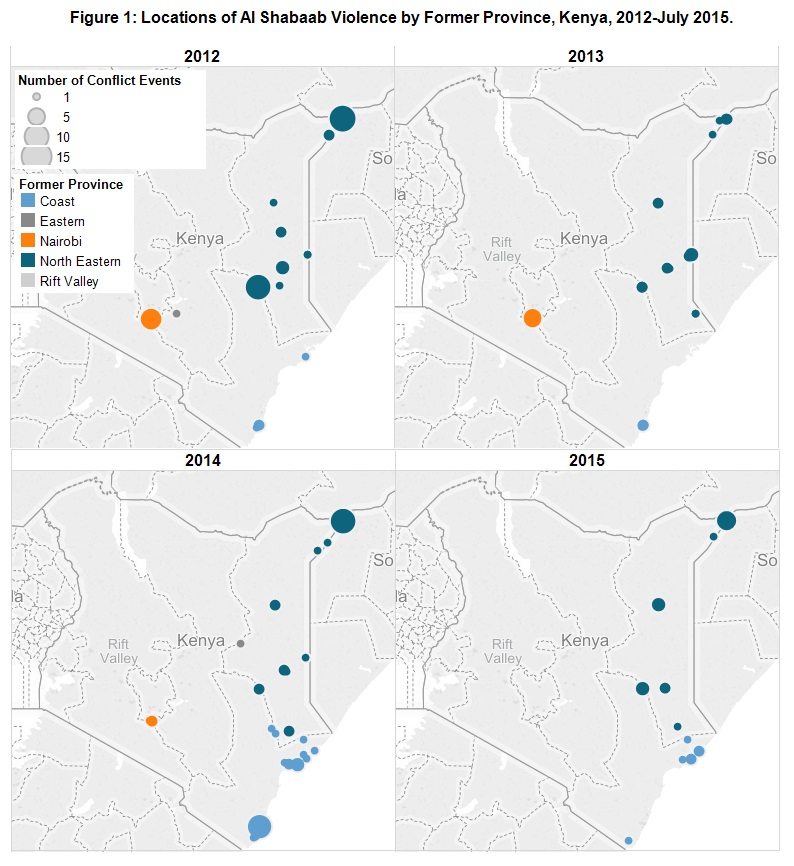

Al Shabaab’s profile in Kenya reflects a three-pronged evolution in strategy by the group. First, the group has been concentrating its activity in the Coastal and North-Eastern provinces in 2015, in spite of a heavy presence in Nairobi in 2013 and 2014 (see Figure 1). The conditions in these regions, which are historically marginalised and under-developed compared to much of Kenya, are being strategically exploited by Al Shabaab in a refocusing of their energy and resources away from the capital city, and towards these more peripheral communities.

A related second development is the solidification of a strategy of increasingly deliberate, selective targeting of civilians, with Al Shabaab explicitly targeting victims perceived as outsiders in the community. The Mpeketoni attacks in June 2014 (BBC News, 2014), the targeted killings of non-Muslims at the Kormey quarry in December of last year (BBC News, 2014) and at Garissa University College in April of 2015 (Reuters, 2015) are ready examples of this trend. July witnessed another high-fatality attack in which 14 people were killed in an overnight attack in Mandera, which Al Shabaab described as deliberately targeting ‘Kenyan Christians’ (CNN, 2015). The group has clearly established a pattern of explicitly isolating non-indigenous or non-Muslim civilians in targeted attacks, in a tactic which strategically exploits Kenya’s religious and ethnic divisions, and issues around access to land, power and privalige (Lind and Dowd, 2015). This tactic differs markedly from the earlier strategies of the group, which in 2011 and 2012, engaged in lower-intensity, indiscriminate attacks in Nairobi, characterised by grenade attacks on buses, shopping areas and social venues. The evolution illustrates Al Shabaab’s deft adaptation to political conditions in Kenya.

Finally, and perhaps most ominously, the group is now seizing territory– even if only briefly– following a series of reports in May, June and July that Al Shabaab forces had temporarily gained control of remote villages and rural mosques in the country’s North Eastern and Coast provinces. The move echoes the evolution of Boko Haram in Nigeria, which turned to seizing territory rather rapidly, and made quick progress in expanding its control across large parts of Nigeria’s far north-east. In contrast to Boko Haram, Al Shabaab has not reportedly used any violence yet in its takeover of territory, involving only temporary incursions by forces into remote sites, although some seizures have prompted waves of displacement. Moreover, the seizures have been brief and therefore, most likely, symbolic. Like Boko Haram, it is unlikely the group could effectively seize and hold territory for any extended period of time, although their ability to do so even briefly shines a spotlight on weaknesses in two of the continent’s most powerful economies. A final difference worth noting is that in contrast to Boko Haram, Al Shabaab has an organisational legacy of ruling and administering territory in South Central Somalia, where its governing structures and bureaucracy developed over several years of uninterrupted rule. While Al Shabaab in Kenya may, as yet, lack the capacity to hold territory, it has both the ambition and history to govern it.

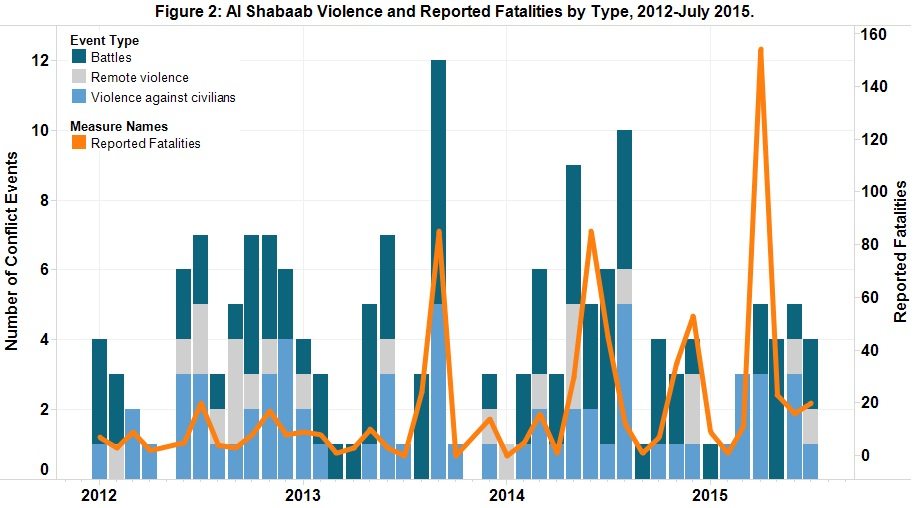

In looking to what the coming months might hold for Al Shabaab violence in Kenya, a fourth pattern in the group’s activity is worth highlighting: throughout its history in Kenya, Al Shabaab violence has been characterised by peaks and lulls in activity levels, with a low level of volatility in 2011-2012, and an increasing stark contrast between spikes of high-fatality violence, and low-activity ‘regrouping’ periods from late-2013 onwards. These spikes are most apparent in September 2013, June 2014, December 2014, and April 2015, and characterised by a gradual reduction in the intervening period between spikes. The Garissa attack in April represents the single most fatal month in the group’s history of violence in Kenya (see Figure 2), but if Al Shabaab’s established cycle of high-fatality violence followed by lower-activity intervening periods holds true, we can expect a circuitous return to high-violence levels in the coming months.

This report was originally featured in the August ACLED Conflict Trends Report.

AfricaAl ShabaabCivilians At RiskConflict MonitoringHuman RightsPolitical StabilityRemote ViolenceViolence Against Civilians