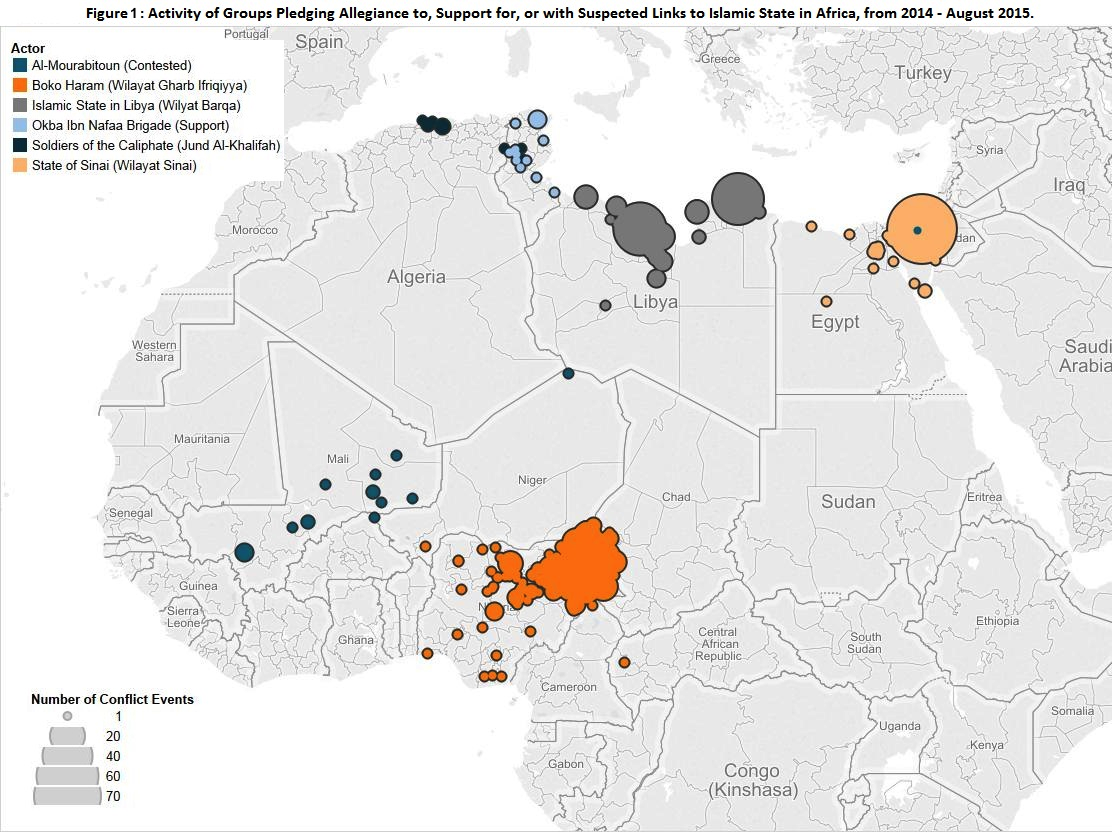

In November 2014, The Islamic State’s recruitment and propaganda publication ‘Dabiq’ announced a strategy to ‘remain’ and ‘expand’ (The Clarion Project, 21 November 2014) in order to consolidate its existing territorial presence whilst spreading the caliphate regionally, and eventually globally to promote disorder and disruption. To date, this stated objective has held true; the group has primarily focused on the “Interior Ring” of Iraq and Syria, whilst extending its reach to the “Near Abroad Ring” (Middle East Security Report, 28 July 2015) establishing Wilayats (translated as power and authority but often used to refer to provinces) and affiliate networks in Algeria, Egypt, Libya and Pakistan amongst other countries (see Figure 1).

With international attention pivoting towards the Islamic State’s operational presence in Libya, there have been several attempts to pre-empt their advance both within and outside of Libya. Libya is seen as the Islamic State’s ‘African hub’ (WSJ, 18 May 2015), offering fertile ground for expansion into North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa as well as Europe (The Telegraph, 17 February 2015). The Islamic State’s intentions in Libya have led to brutal displays of force against civilian populations largely concentrated along coastal areas. This has produced and exacerbated the already dramatic humanitarian crisis from a civil war that has displaced thousands of citizens. Libya’s coastal proximity to mainland Europe has made it a key destination for Sub-Saharan migrants to attempt the treacherous sea-crossing resulting in over 200 bodies washing ashore in Zuwara this week (The Guardian, 28 August 2015). The informal economic activity of the Islamic State, which has significant influence over smuggling networks through coercion of local groups and control over ports, has refocused attention on the potential for Islamic State militants to infiltrate Europe from the Mediterranean Sea.

Thus, the key question for many has been ‘where next’? Will the Islamic State spread south to Sub Saharan Africa and build upon its ties already fostered by Boko Haram in Nigeria, or does expansion into Europe loom close? One way to comprehend this is by looking at the nature of the Islamic State franchise beyond its immediate territorial control. U.S. officials and Middle East analysts have commented that although a number of disparate regional groups have pledged allegiance or support to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, “those vows haven’t translated into significant efforts by Islamic State to establish ties or expand its outreach” (WSJ, 18 May 2015).

North and West Africa

Across North Africa, areas with strong links to AQIM networks have proven vulnerable to Islamic State expansion. However, despite large numbers of foot soldiers from pro-Al Qaeda groups switching allegiance to the Islamic State, it does not automatically follow that control will extend to these regions. Whilst many groups will have a higher proclivity towards Islamic State absorption, their expansion has exposed rifts between AQIM and Islamic State across the Middle East in Iraq and Syria and North Africa in Libya.

A new development last week may have signalled an obstacle for the Islamic State’s network across the Maghreb after their supporters designated Mokhtar Belmokhtar an enemy (International Business Times, 28 August 2015); accusing him of aiding the fightback by local Al Qaeda-affiliated groups in Derna, Libya. Mokhtar’s linkages and influence across Islamist groups in North Africa suggest that he could be a key broker in the initial success of the Islamic State to expand regionally into West Africa. Should MUJAO and Al-Mourabitoun link up operationally with Boko Haram or state their intentions to coordinate with the Islamic State clearly, they could form a nucleic command structure to operate and conduct attacks across Mali, Mauritania, Ivory Coast and other West African countries (Zenn, 4 August 2015). Recruitment drives have reached into Ghana after a number of university students travelled to Syria (BBC News, 28 August 2015). Whilst this recruitment is for the outward movement of fighters to Syria, there is potential for these networks to flourish once fighters return home presenting a number of challenges for these countries.

Yet Belmokhtar’s apparent refusal to acknowledge allegiance to the Caliphate and the possibility of burgeoning divisions in Al-Mourabitoun over their allegiance to Islamic State (The North Africa Post, 18 May 2015) illustrates the complex politico-religious choices of these disparate groups and further highlights difficulties of assessing how the Islamic State can make inroads into Africa by penetrating existing AQIM networks. It does however highlight the potential vulnerability of West African regions such as Mali through the interconnected Islamist networks that can be coerced, exploited or co-opted by the Islamic State.

Nigeria

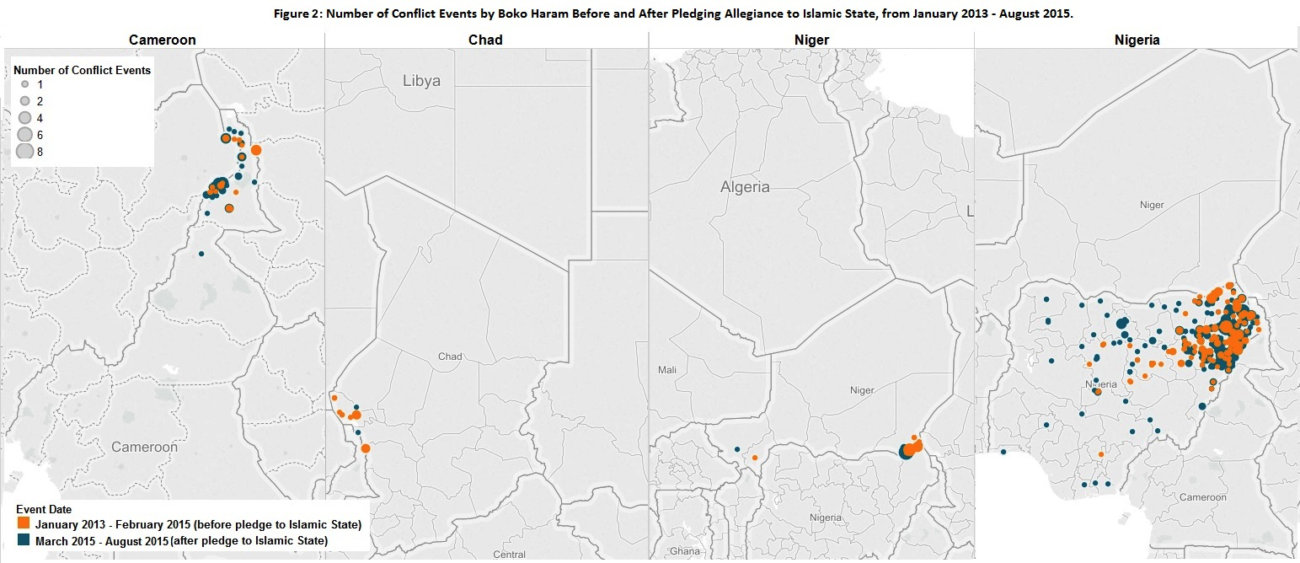

In March 2015, the leader of Boko Haram pledged allegiance to the Islamic State. Since the transition, uncertainty has surrounded the level of operational communication and influence this has had on the activity of Boko Haram, now referred to as Wilayat Gharb Ifriqiyya (West African Province of Islamic State). It remains contested whether joining a larger umbrella movement holds insight into group strength and dynamics. Although some commentators suggest the pledge indicates a pre-emptive move by a threatened Boko Haram to balance against the military offensive in Borno State before the Nigeria elections, Jacob Zenn points to exchanges between Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and Boko Haram that had already been taking place months previously (Jihadology, 4 August 2015).

Since Abubakar Shekau’s pledge was accepted around March 7th (WSJ, 13 March 2015), Boko Haram attacks have diffused with more prominent cross-border activity (see Figure 2). This is attributed to revenge attacks on Cameroon, Niger and Chad for supporting the military offensive potentially influenced by growing Islamic State integration. This may demonstrate a geographical shift in agenda, where it is no longer necessary for attacks to cluster in a Nigerian-centred insurgency (Jihadology, 4 August 2015). Whilst it is difficult to ascertain with certainty whether this indicates an early stage IS expansion, it again demonstrates the potential for the Islamic State to piggyback on existing radical groups and the changing nature of conflict and distribution of violence since Islamic State became a regional player.

Europe

In terms of an Islamic State threat to Europe, the White House spokesperson Josh Earnest provides a useful caveat for interpreting the current threat level.

“I think it’s important for us to differentiate between the spread of Isil and individuals who are trying to attract attention for themselves by claiming an association with Isil…” (The Guardian, 21 February 2015).

Whilst the potential for expansion in North and West Africa appears to rest upon existing group coordination with a degree of centralised command, lone wolf attacks appear to be the future trajectory in Europe. Presently, Hegghammer and Nesser (2015) identify that isolated attacks conducted by individuals sympathetic to the Islamic State rather than a concerted group effort to organise major attacks characterised the main security threat to Europe. Although Hegghammer identifies that between the period of 2011-mid 2015, 30 out of 69 ‘Jihadi’ plots in the West showed a connection to the Islamic State, he is tentative as to whether these are ‘organised’ or ‘inspired’ by the Islamic State (Jihadology, 10 August 2015).

Different perspectives on expansion

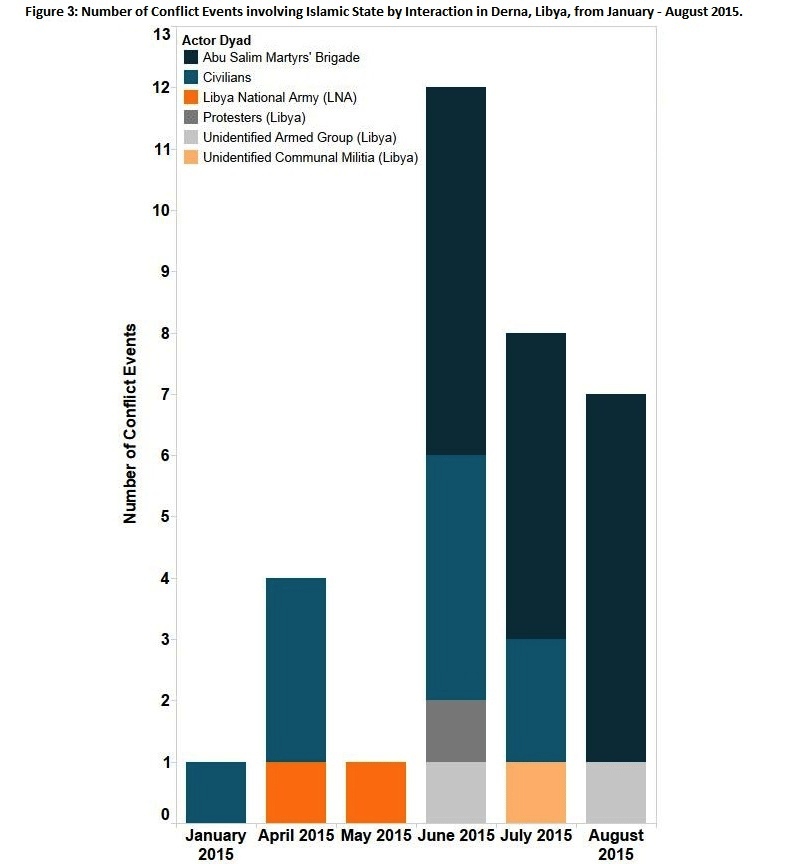

The assumption that the Islamic State has a clear mandate to expand may not be the most effective way to predict their future expansion. Many analyses that start from this assumption assess the geographical and micro-political factors that increase the propensity of an area to be targeted by Islamic State militants. For example, locations with a history of harbouring radical groups, returnee fighters from the conflict in Syria and Iraq, porous desert borders and the absence of functioning state institutions. Rather than taking this as the foundation to understand where (and whether) the Islamic State movement will expand next, it is more fruitful to explore the processes driving this expansion. The fact that the Islamic State has ramped up its activity and presence in Libya demonstrates that the diffusion of their activity is not necessarily indicative of group strength. Conflict has flared around Derna in recent weeks (see Figure 3), with a local Abu Salim Martyrs’ Brigade regaining control of the city and pushing Islamic State militants to farm areas to the east.

“ISIL is very much like a balloon,” said one senior defense official. “When you squeeze it, it moves elsewhere. They’ve shown that in Iraq, to some degree, where they live to fight another day” (WSJ, 18 May 2015).

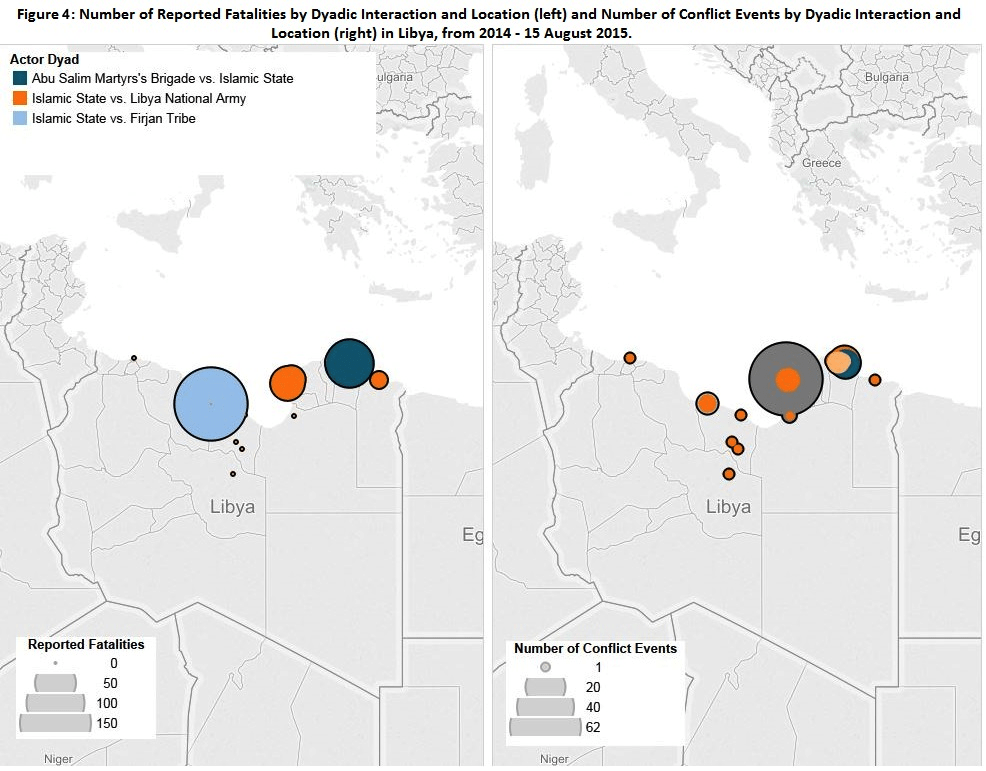

Thus from this standpoint, whilst it is critical to identify where Islamic State are likely to expand globally, in order to sufficiently address this, analyses need to overcome the overly narrow focus on Islamic State as the unit of analysis to examine the strategies of state and non-state actors tackling Islamic State. The map below illustrates the diverse nature of the fight against the Islamic State by highlighting the multitude of actors engaging with and shaping the strategic calculus of the Islamic State in Libya (see Figure 4). As a result, we may develop a more accurate indication of whether their diffusion is an indication of growing strength, or whether their territorial diffusion is an adaptive strategy as a result of being pushed out of areas by counterinsurgency or local uprisings. Building on the work of Schutte and Weidmann (2011), further research is needed to distinguish between the relocation of violence and spatial expansion of violence to understand the ability of Islamic State groups to grow their power base. The activity of groups affiliated to the Islamic State in Libya and Nigeria show the potential for patterns of contagion, but relatively little is understood about the mechanisms driving this. It is uncertain whether the movement of violence over borders in Nigeria and increasing territorial activity outside of Derna and Sirte in Libya are a result of growing group strength or successful incursions by state forces.

Understanding whether the movement of conflict out of one area into another indicates an adaptive strategy by weakened militants and whether spatial expansion of the scope of conflict signals growing strength and escalatory patterns will enable an alternative assessment of the prospect of Islamic State expansion further into Africa in the near future.

This report was originally featured in the September ACLED Conflict Trends Report.