Peaceful protests constitute 87% of recorded events in Cambodia and Vietnam. This may be reflective of the issues currently engaging these societies, but also, local media reporting is limited by strict state censorship. The state limits not only the publication of protests in local and international press but also often restricts public gatherings that could present potential threats to the government. From January through August, the press in Vietnam and Cambodia have released a slow trickle of reports which often detail insignificant events like protests concerning excessive noise. Likely a tactic used by the regime to distract both the citizens and the international press from more pressing issues, the result is a disproportionate amount of protests on mundane issues while human rights violations often go unacknowledged.

CAMBODIA

The Cambodian government frequently implements harsh crackdowns on protests against the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP), which came into power through disputed parliamentary elections in 2013 (HRW, 2015). Civil society groups targeting social welfare issues, rather than justice and human rights, experience a lesser degree of state intervention (Freedom House, 2015). Therefore, about 50% of protests in Cambodia demand wage increases and better treatment of workers. However, the government has taken actions to combat these protests as well, occasionally resorting to violence to break them up (HRW, 2015). In January, security forces killed four protesters campaigning for better working conditions in the capital (Freedom House, 2015).

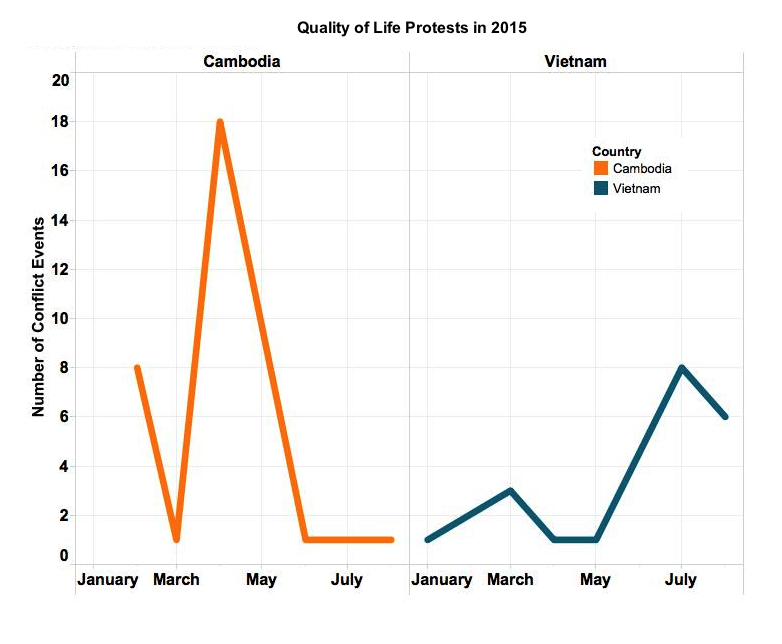

Cambodia experienced 42 work-related protests since the beginning of January, with a spike of 15 relevant events in April alone. 86 protests have been reported in Cambodia in 2015. The other protests were mainly political or related to land disputes, and Cambodia’s security forces often forcibly dispersed the gatherings.

In April, approximately 500 workers from three garment factories protested in Phnom Penh to demand that government officials intervene after their employers refused to meet their demands for food, transportation subsidies, and better working conditions. Protests like these are representative of the majority of protests in Cambodia. It is striking that reported protests are so heavily oriented toward raising the standard of living in a country where the government uses excessive lethal force and exercises arbitrary detention and torture (HRW, 2015). Either the government of Cambodia is publishing protests to assuage international observers or the government is trying to distract the populace from more pressing issues.

VIETNAM

The Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) has maintained one-party rule in Vietnam since 1975. Growing public discontent about the lack of basic human rights challenges the CPV’s grip on power, especially as social media increasingly facilitates the expression of these ideas. In addition to tightly controlling the media, the government requires official approval for public gatherings, allowing it to stifle any protests they deem unacceptable and to punish those who violate this order (HRW, 2015).

In 2015, the Vietnamese media reported 42 instances of political violence in Vietnam. Of these, 81% were non-violent protests. Many of these protests focus on issues like dust, pollution, fair compensation for labor, and ecosystem preservation. For example, in April, thousands of protesters blocked a highway in southeastern Vietnam to protest a nearby power plant they said was covering their homes with dust (Radio Free Asia, 2015). In July, residents in the central province of Thanh Hoa set up tents and lived in them for one week to block the construction of a landfill site they said would pollute their homes’ surroundings (Thanh Nien News, 2015).

Most of the reported protests target private companies or local governments, but rarely the national government. This is likely the result of the CPV’s tight grip on the media outlets. Allowing protests that target seemingly minor issues relative to the frequent violations of basic freedoms occurring in the country distracts from the real issues at hand and casts the CPV in a more favorable light. The government of Vietnam may sanction the release of minor protests to quell criticism from international allies and organizations like the UN as well as mediate Vietnam’s image in the international press. By reporting on local frustration over dust, for instance, Vietnam retains its image as a safe, developed country. Reports leaking out of Vietnam from international journalists and NGOs suggest dust is not the most pressing issue: sources reporting independently of the CPV reference human rights abuses including systemic use of corporal punishment, unfair detentions, and police use of lethal force (U.S. Country Report, 2014).

In sum, protests centered on improving citizens’ quality of life may be occurring throughout Southeast Asia, though it is more likely that the politically relevant events that are occurring go under-reported or unacknowledged throughout the region. Understanding the nations’ motives to selectively release snippets of innocuous protests is critical in framing the political environment in Southeast Asia.

This report was originally featured in the August ACLED-Asia Conflict Trends Report.

AsiaCivilians At RiskGovernment RepressionPolitical StabilityRioting And ProtestsViolence Against Civilians