The Pakistani Armed Forces launched operation Zarb-e-Azb on June 15th 2014. Hailed as the first “comprehensive operation” (The News June 15 2014) in Pakistan, the state deemed it a required response after the joint Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) June 8th 2014 attack on the Jinnah International Airport in Karachi. A newly elected government gave permission to the armed forces to weed out local and foreign militants in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas. Historically, far reaching military operations against militant organizations in Pakistan have been rare, and often with a limited focus. The Musharraf era operations in 2009 targeted one militant faction at a time. In Operation Rah-e-Nijhat, the Pakistani military pursued TTP militants in South Waziristan. Operations in the past, however, were criticized by analysts and the media as empty measures, failing to address the root causes of extremism and strategically allowing other militant groups, such as the Haqqani Network, to flourish (Haider 2014).

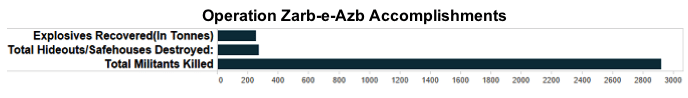

Over a year later, Zarb-e-Azb has been hailed a military success by the Pakistani armed forces, who estimate that they have eliminated at least 2,919 terrorists (ACLED Data), destroyed 873 hideouts and safe-houses and recovered 253 tonnes of explosives (The Express Tribune June 13 2015). Perhaps more critical is how the success of the operation changed local and international public perceptions toward the state’s role in combatting terrorism in Pakistan and abroad. When the operation began, local sentiment focused on the influx of Internally Displaced Peoples (IDPs) from the tribal belt and on the assumption that the operation was an attempt by the army to once again hijack the democratic process in Pakistan –whose first democratic transition of power occurred in May 2013. In mid-2014, international allies were concerned with Pakistan’s ability to fulfil the operation’s mission statement, with commentators dubious of the objective of ridding the tribal belt of all militant factions (Haider, 2014).

One year on, while public opinion on IDPs and their treatment is still a contested topic, with IDPs protesting at least once every month since the start of the operation, public sentiment towards the army is encouraging. The army has displayed a commitment to expunge local and foreign groups, as well as those it has considered allies in its past, such as the Haqqani Network. It has not, to date, tried to dislocate the power structure in Islamabad. Internationally, Pakistan has been lauded by several countries, including the United States (Express Tribune 6 November 2014) for its commitment over the last year to abandon its previous policy of “strategic depth”. The policy allowed for intelligence agencies to back militant outfits in Afghanistan and India with the pretext that the knowledge they provided gave Pakistan an advantage in regional politics (Kronstadt 2008, p13).

Amongst the militant groups the Pakistani military is fighting in FATA, TTP, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi and Jundallah are the only three Pakistani-based militant outfits, the others, like IMU and EMIT, are foreign. In addition to foreign fighters and domestic terror cells, the army has had to factor in US drone strikes. Pakistan argues these operations undermine local efforts to eliminate extremism and radicalisation in the tribal belt. As Zarb-e-Azb gained momentum, IMU and EMIT presence in the tribal belt has diminished, with the Army claiming that by August 2014, just a month into the operation, the vast majority of the 500 militants killed were from these groups (Khan, 2014, 21). Additionally, the divisions created in the TTP as the operation unfolded– including infighting and the launch of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) to whom the IMU chief declared allegiance — meant that the safe haven created for foreign militants was now less stable. Although Uzbeki and Tajik militants are active intermittently in pockets of Afghanistan, they have largely retreated from Pakistan since Zarb-e-Azb began, as over a 100 were killed the first two weeks of the operation (DAWN, 14 June 2014).

The Haqqani Network’s relationship with Pakistan has taken a sharp turn since the operation began in 2014. The Network’s presence in the region dates back to the early 1970s at the time of the Marxist revolution in Afghanistan, when the Network’s leader operated rebellion efforts from Miranshah, North Waziristan (Gordon, 2015). The Haqqani Network’s rise during Taliban rule in Afghanistan made them a key component of Pakistan’s strategic depth policy, a tie that would prove difficult to sever in the post 9-11 security environment. Lieutenant General Hamid Gul, who served as the Director General of the ISI between 1987-1989, was a key figure in creating militant resistance groups in Afghanistan during the Soviet occupation, and then used the same strategy in Kashmir in Pakistan. His involvement with separate militant groups in the region earned him the title of the “Godfather” of Pakistan’s geostrategic policies. He is often cited as proof of the connection between the military and militant networks in Pakistan, often supporting negotiations with violent groups (Rondeaux, 2009). The intricate networks built between the Taliban, Al Qaida, and The Haqqani Network in Afghanistan was a key component of Pakistan’s security narrative, as well as the target of the US mission in Afghanistan.

9/11 further complicated the intricate network, as Pakistan, hesitant to abandon old ties and stratagems but pushed into declaring allegiance with the US on the War on Terror, adopted a narrative that separated the “good” from the “bad” Taliban (Ali, 2014). Pledging to rid the nation of ‘bad’ Taliban, Pakistan offered safe havens to militants being attacked in Afghanistan by the US, with the understanding that these militants would not carry out attacks on Pakistani soil. This often lead to contention with Afghanistan and the United States, as groups such as the Haqqani Network were not attacking Pakistani soil, they often teamed up with Afghani Taliban to carry out joint attacks in Afghanistan. By providing these groups safe haven, Pakistan was implicit in prolonging the War on Terror in Afghanistan (Khan, 2014).

Pakistan’s narrative of good and bad Taliban was put to the test in the years to come as the TTP made further gains in the country and the United States began its drone warfare program in the region. The military proved that it had abandoned the policy of strategic depth in favour of a policy of no negotiations, hard military action, and a strengthening of domestic and international relations through official democratic channels, as opposed to secretive meetings with proscribed outfits. The gains made by this particular break in national policy by Pakistan has resulted in a narrative shift for the state, as well as greater support and diplomacy on the international platform, with the United States appreciating Pakistan’s role in defragmenting the Haqqani Network and Al Qaida in the region (The Daily Times 4 March 2015).

In addition to a successful disassociation with terrorists and local narrative shift, Operation Zarb e Azb also gained military successes. Haqqani Network hideouts have been destroyed and several important commanders have been captured or killed. Foreign Al Qaida commanders have been captured and killed in Karachi, indicating that their hideouts in the tribal belt are no longer safe areas (Times of India January 9 2015).

When Zarb-e-Azb began, the Pakistani military publically requested that the US military stop drone attacks on Pakistani soil, a request the US obliged to for the first six months of the operation. Since then, there have been sporadic periods of consistent drone attacks in border areas with Afghanistan. Pakistan repeatedly condemns such attacks and often does not give access to journalists to verify who was targeted and killed. However, ISPR reports consistently mention that among those killed by drone strikes are often foreign militants from the Afghan side of the border. While the number of drone strikes has decreased since an all time high in 2010 (The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, 2015), the Pakistani military maintains that their efforts are hindered by US drone strikes.

With the rise in attacks in Afghanistan however, Pakistan has struggled to fully sever ties with with militant groups. This month, Afghani President Ashraf Ghani, in the wake of a militant attack in Kabul that killed over 50 people, blamed Pakistan (Dawn 10 Aug 2015). While Pakistan is working on shifting elements of its narrative, there are other deeply entrenched beliefs that prove immutable. The military’s response to Afghanistan’s accusations was to blame India, and focused on Indian motives to destabilise Pakistan and jeopardise its relations with Afghanistan and the United States. This cycle of blame has prevailed since Pakistan’s independence.

Overall, activity by external forces has decreased in Pakistan’s tribal belt since the start of Operation Zarb-e-Azb, and the army has worked not only to eradicate terrorism in the region, but also on shifting the narrative. Abandoning the policy of strategic depth meant that safe haven provisions for foreign militants was off the table. Perhaps as a result, a nation wide commitment to eliminate all radicalised elements in society has translated throughout the country. Thus far, there have been no attacks by the Haqqani Network in Pakistan in 2015. US Security advisor Susan Rice, on her recent visit to Pakistan contended that more could be done by Pakistan to dismantle the Haqqani Network (VOA News 31st August 2015). Pakistan, adamant to show commitment, has started what it calls the final push, with a major ground and air offensive, killing at least 89 local and foreign militants in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas in the last two weeks of August. Pakistan’s neighbors are careful to assess Operation Zarb-e-Azb’s effectiveness for them, and attacks on Pakistani soil by other factions have continued, the operation is far from over and Zarb-e-Azb is been a key element in Pakistan’s first attempt at a radical policy shift since 9/11.

This report was originally featured in the August ACLED-Asia Conflict Trends Report.