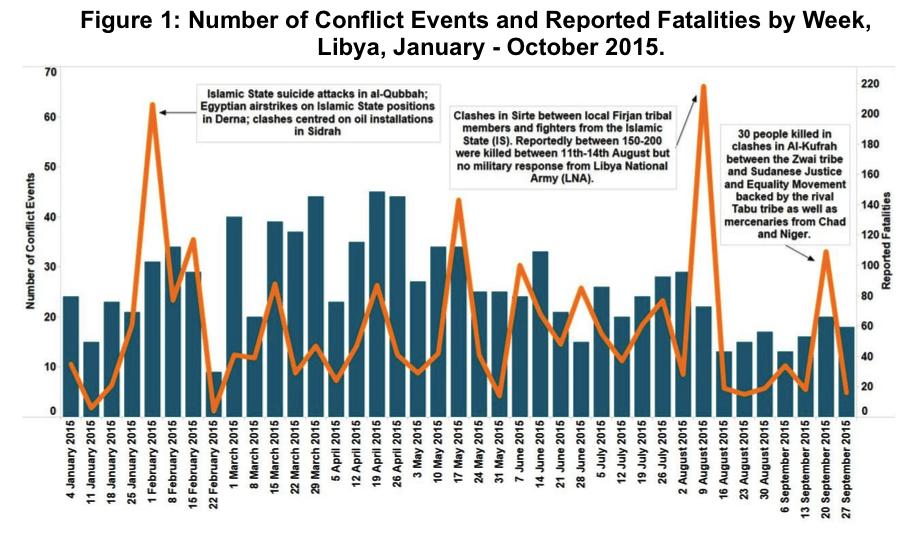

Episodes of political confrontation continued to fall throughout September, yet cause for celebration is a far cry for most Libyans (see Figure 1). The intensity of attacks to the West and South of Tripoli have scaled down over the last few months, however this should not mask the polemical nature of Libya’s conflict and potential for escalation.

The 20 October marks the expiry of the House of Representatives’ (HoR) mandate and the proposed power-sharing agreement has resulted in a number of unilateral moves that could aggravate the conflict. The fall in conflict events is no more indicative of a Libya that is closer to peaceful settlement than the presence of stalling mediation attempts by the United Nations. In fact, Libya appeared to be set on a collision course towards the expiry of the House of Representatives mandate on 20 October, until the HoR unilaterally declared amendments to the 2011 Constitutional Declaration to extend its term (Libya Herald, 5 October 2015), complicating further the future of a country whose immediate fate already hangs in the balance.

That balance is less between rival parliaments and more in the hands of General Khalifah Haftar, who has capitalised on the absence of a centralised state and is likely to benefit from the failure of the Tripoli and Tobruk-based parliaments to reach consensus for a unity government. Talk of Haftar forming a military council to rule Libya increases the risk of his spoiler activity in the coming weeks, where he has already been accused of preventing a peaceful transition. Haftar launch the latest offensive in Benghazi on 19 September, dubbed ‘Operation Doom’, one day before the UN agreement was set to be signed. This is not an isolated incident; Haftar has also bombed Mitiga airport in Tripoli before delegates from the GNC were due to travel to peace talks.

Even if the HoR’s mandate extension is recognised, Haftar will want to establish some daylight between his forces and the government he has represented for over a year to position himself for a military takeover, should a signed agreement fail to materialise. This looks increasingly likely as the two central points of impasse concern the composition and binding powers of the State Council (comprised predominantly of GNC figures) and Gen. Haftar’s role in the security apparatus — the GNC stands in ardent opposition to Haftar as army chief. Signs of tension between Haftar and the Tobruk government continue to emerge as Haftar assumes the role of both the protagonist for the HoR as well as its antagonist. Discussions over the appointment of a defence minister reportedly turned sour leading to Haftar asserting his capability by instructing his affiliated militias to forcibly block the HoR Prime Minister Abdullah al-Thani from boarding a plane to Malta (The Digital Journal, 16 September 2015).

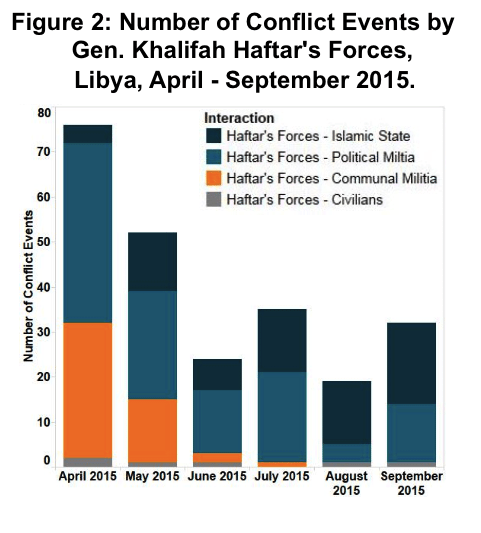

Haftar further compounds the prospects of settlement by abjectly refusing to engage in negotiations with rival groups and Islamists affiliated with the GNC, a stance that sits uneasily when viewed with his ambiguous policy towards Islamic State militants (see Figure 2). Brutal Islamic State attacks on local Firjan populations in Sirte were virtually ignored by central command in mid-August. That most of these fighters were Salafist and the bulwark of Haftar’s strongest fighters are ultraconservative Salafists (New York Times, 1 October 2015) highlights how Haftar privileges his own power over building a cohesive national military, and ensuring security.

Small bouts of fighting also erupted between battalions once united under the Operation Libya Dawn alliance. The role of Misrata in active fighting has subsided in recent months but ill-discipline is causing in-fighting between individual militia members. As the Libya Dawn alliance breaks down, a new coalition announced itself in late September as revolutionary brigades from Tobruk and Al-Bayda mobilized under the Shura Council of Derna Mujahideen, offering support to the Abu Salim Martyrs’ Brigade fighting Islamic State militants in areas around Derna and Al-Fatayah. This mobilization illustrates the extent to which the Libya National Army is failing to address IS expansion and how local populations and communal groups are transforming into sites of power and resistance.

The Ali Hassan Al-Jabar Brigade joined the assault against IS only to find a week later that Haftar-aligned militias raided their Al-Bayda headquarters, seizing control (Libya Herald, 28 September 2015). The irony is that as Haftar pursues the international community to lift the arms embargo in order to adequately equip his forces to tackle ‘extremism’, his obstruction to local community mobilization and deliberate targeting of militias fighting IS maintains his cause and allows IS to, at least temporarily, remain.

All eyes rest on 20 October and how internal and external players interpret the Constitutional amendment and legitimacy of the HoR. The absence of an agreement looks increasingly likely which after 20 October could gift the GNC more legitimacy in the eyes of international powers, even if only symbolically. The uncertainty this brings to Haftar’s future position is likely to galvanize his bullish approach to peace and the prospects for a full breakdown in negotiations looms close. Libya is in a catch-22: demote Haftar from his commanding position and expect progress in reaching a mutual position in the UN Peace Agreement. Haftar and his forces are likely to resist this violently and Libya may struggle to appoint a substitute commander-in-chief that can integrate such complex networks of fighters into formal military structures. Alternatively, leaving him in place eliminates any prospect of accordance, and increases the risk of sedition on multiple fronts from blocs that oppose his legitimacy.

This report was originally featured in the October ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.