In 2015, Tunisia has seen a substantial increase in conflict activity across the country, as conflict events and reported fatalities reached their highest levels since the 2010-2011 uprisings. Twelve months after the parliamentary and presidential elections that marked the end of the democratic transition, the Tunisian government grapples with widespread socio-economic malaise and an escalation of Islamist violence on its territory.

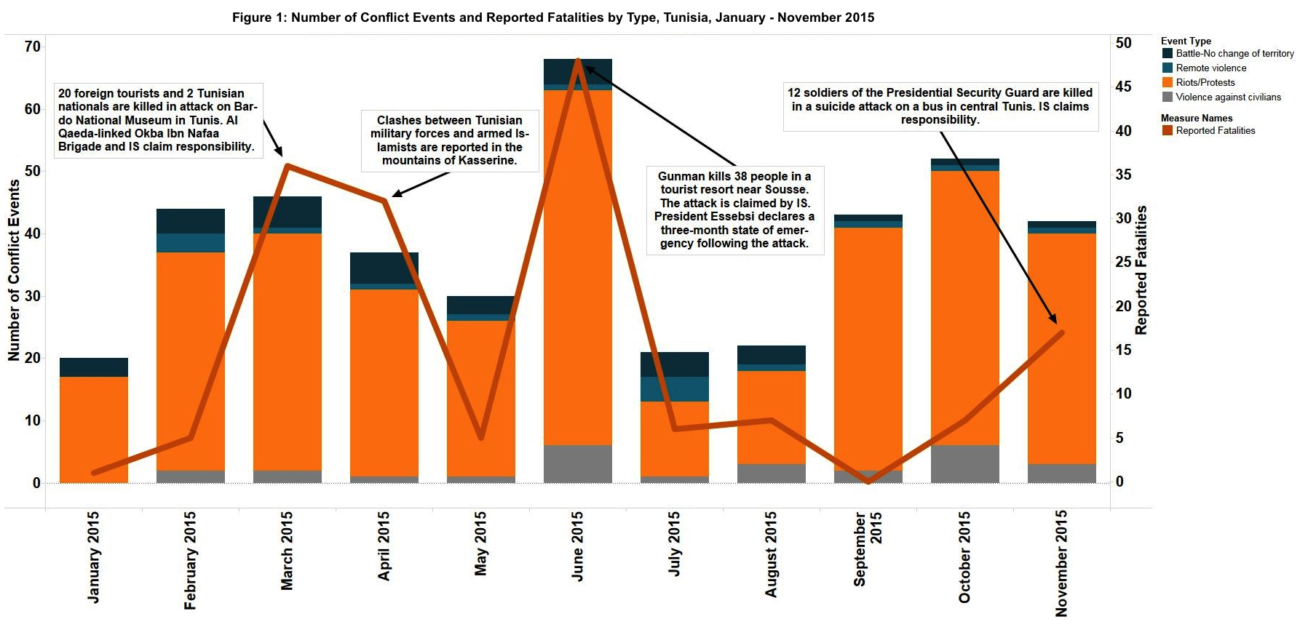

Figure 1 shows the evolution of conflict patterns throughout 2015, highlighting some of the key developments witnessed over the year. On the one hand, riots and protests account for the vast majority of reported events and saw the largest increase in both absolute and relative terms compared to 2014, reflecting the growing discontent in Tunisian society. On the other hand, whilst organised violence diminished as a proportion of total conflict events, the rise in the number of reported fatalities points to an ongoing escalation of violence. Additionally, as Islamist militias intensified their activity on Tunisian territory, the number of civilian fatalities has increased by four times in 2015.

The two armed assaults on Bardo National Museum and on a tourist resort in Sousse, and the recent suicide attack on board of a bus of the Presidential Security Guard in central Tunis, suggest that Islamist militias have significantly scaled up their tactics. While in previous years armed Islamists mainly targeted secular politicians and engaged in clashes with state forces in the country’s west, violence against foreign nationals has been instrumental in undermining the country’s profitable tourism industry and gaining wider resonance worldwide.

These events reflect the different strategies pursued by Islamist militias in Tunisia. The dissolution of the former Salafi organisation Ansar Al-Sharia in Tunisia (AST) in 2013 led to the emergence of a number of small militant groups and cells throughout the country (Libération, 18 March 2015). In western Tunisia, the Okba Ibn Nafaa Brigade has established a “pocket of resistance” in the remote and mountainous areas near the Algerian border. An offshoot of Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQMI), the group has engaged in several clashes with the army and in sporadic raids on civilian population, while controlling smuggling routes across the Algerian border (International Crisis Group, 21 October 2014). However, members of the Okba Ibn Nafaa Brigade claimed responsibility for the raid on Bardo national museum, suggesting either a change in the group’s strategies or the emergence of a splinter sympathetic towards the Islamic State (IS) organisation.

IS has not yet established a permanent base in the country. While thousands of young Tunisian fighters have joined the Islamist ranks in the Syrian civil war, IS is believed to have sponsored the attacks against foreign tourists earlier this year. According to intelligence reports, some of the gunmen who carried out the murders in Tunis and Sousse had received military training in Islamist camps in Libya (The Guardian, 30 June 2015; Radio France Internationale, 26 November 2015). At the core of IS’ strategy is the belief that derailing the democratisation process and provoking a security clampdown would further alienate Tunisia’s youth and promote radicalisation.

The unprecedented sequence of attacks against civilians and armed forces prompted the government’s immediate response. Following the June attack in Sousse, state authorities introduced a three-month state of emergency along with a series of draconian measures, including the dismissal of around twenty imams across the country. The state of emergency, lifted in early October, resulted in a considerably diminished conflict activity (see Figure 1). However, these exceptional measures met widespread resistance and generated protests across the country. In Sfax, demonstrations against the dismissal of the imam in the city’s Grande Mosquée disrupted the Friday prayer for several weeks. In the country’s south, the closure of the Libyan border provoked popular resentment among the population in Medenine and Tataouine, where the local economy relies heavily on cross-border smuggling. Similarly, in August, the violent repression of teachers’ protests in Sidi Bouzid sparked a wave of unrest in several provinces (ACLED Trends Report, September 2015).

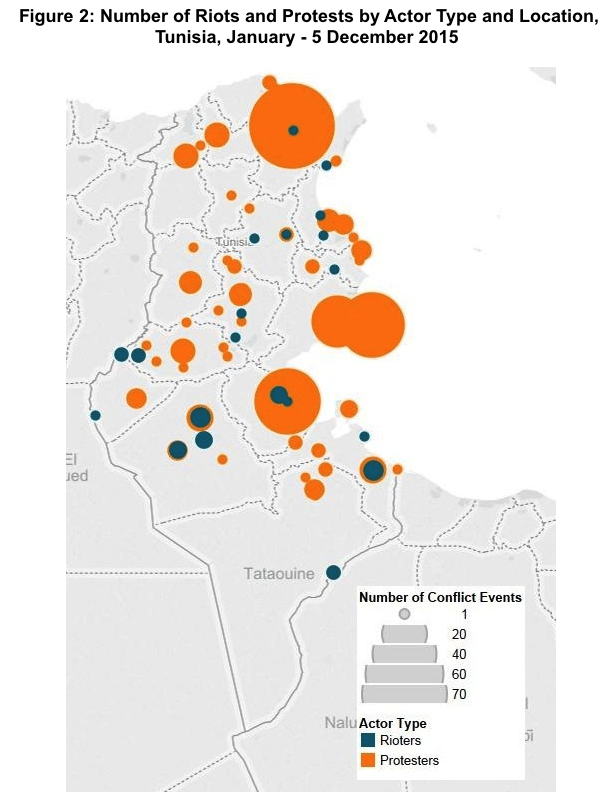

The escalation of violence witnessed in 2015 revealed the structural weakness of Tunisia’s democratic institutions. On the one hand, the existence of major flaws in the security apparatus has led the government to rely frequently on emergency laws (International Crisis Group, 23 July 2015; Agence Tunis Afrique Presse, 25 November 2015). On the other hand, the increasing insecurity has unveiled the weak outreach of state institutions in the peripheral western provinces. A striking example is the recent killing of a Kasserine-born teenage shepherd accused of spying for the government, which disclosed the state of neglect of these areas to public opinion and fostered frustration among local populations. The higher incidence of violent demonstrations recorded in south-western Tunisia (see Figure 2) also points to the widespread discontent with the current socio-economic situation.

As many observers have noted, these security challenges require measures other than repression alone (Le Monde, 2 December 2015). Tunisia’s authorities need to concentrate their efforts into reducing the distance between institutions and citizens, promoting a human-rights-based security sector reform and addressing the country’s socio-economic disparities. However, the recent divisions within the ruling party Nidaa Tounes, as well as within the coalition government, are unlikely to defuse social and political tensions and promote the formulation of cohesive and comprehensive security policies in the short term (Jeune Afrique, 30 November 2015). Thus failing to provide an adequate response may eventually risk undermining domestic stability and the country’s democratic institutions.

This report was originally featured in the December ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.