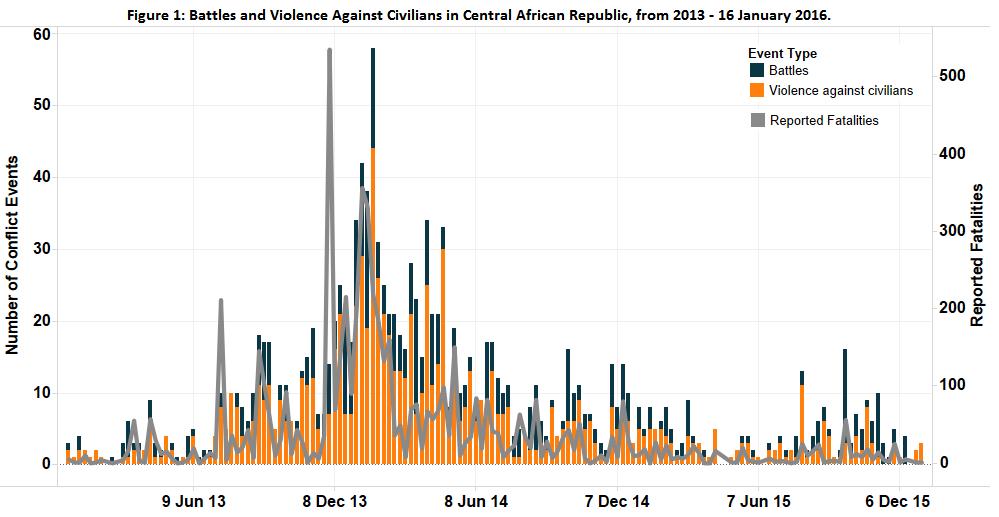

The Central African Republic (CAR) has faced increased insecurity and violence since Séléka rebels marched on the capital, Bangui, and ousted then-President Bozizé in 2012 (Townsend, 27 July 2013). Since the height of violence in late 2013 / early 2014, the conflict has remained persistent and widespread (see Figure 1).

To contribute to the insecurity citizens of CAR already face, other conflict agents also continue their activity within the country. Earlier this month, CAR saw the largest kidnapping in recent months by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA); dozens have been abducted, and one villager was killed in the raids (Reuters, 12 January 2016). The Red Cross recently reported that this persistent violence in CAR has resulted in the separation of families; the weak infrastructure in the impoverished country, such as poor road networks, results in a big challenge for those looking for loved ones (IFRC, 19 January 2016).

In January 2014 Interim-President Catherine Samba-Panza called for elections to deal with the disputing political and armed factions. “[The elections] represent the best hope of reuniting the country, one of the world’s poorest, after three years of sectarian violence that has displaced hundreds of thousands of people” (Benn, 30 December 2015). The first round of the elections took place at the end of December after being postponed from mid-October of last year. No winner emerged from the 30 candidates on the ballot (The Economist, 8 January 2016), and a run-off election is scheduled for the end of January 2016.

Two former CAR premiers — Anicet-Georges Dologuélé, a former central banker who served as prime minister from 1999 to 2001, and Faustin-Archange Touadéra, a former math professor who served as prime minister under former-President Bozizé — received the most votes in the first round of the election, and will vie for the presidency (Agence France Presse, 7 January 2016).

That the December elections were largely peaceful (Benn, 30 December 2015) is possibly related to the presence of UN peacekeepers (MINUSCA) deployed in the country. They were joined by the French Sangaris force as well as local security teams to maintain peace (UN, 30 December 2015).

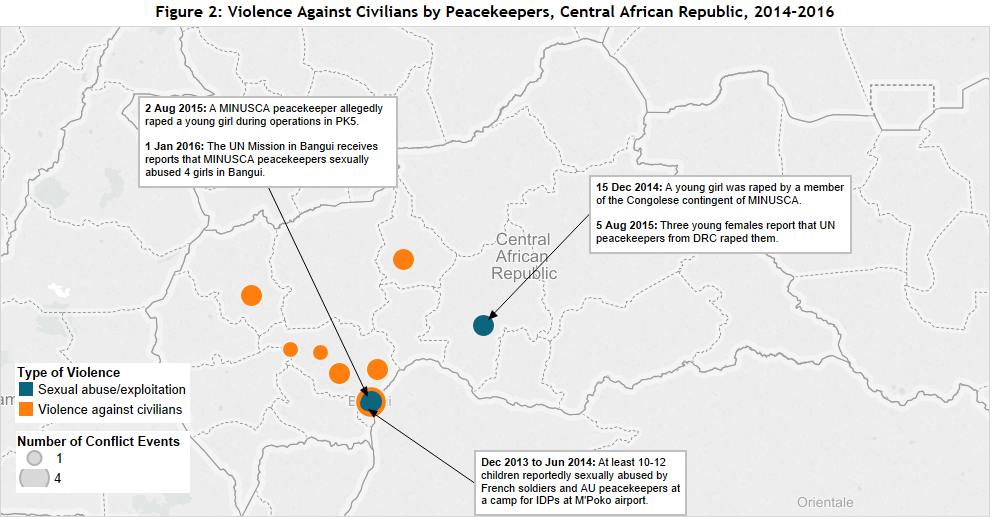

However, this good has been marred by recent reports of sexual abuse in Bangui by UN peacekeepers serving in the MINUSCA mission to CAR (Sieff, 11 January 2016). UN peacekeepers from Gabon, Morocco, Burundi, and France are said to have paid as little as 50 cents in exchange for sex with girls as young as 13, using a prostitution ring in M’Poko, an internally displaced persons’ camp near Bangui (Westcott, 12 January 2016). This case is the latest in a string of similar accusations: in the past 14 months, peacekeepers affiliated with the UN mission in CAR have been accused of 22 other incidents of alleged sexual exploitation or abuse (Sieff, 11 January 2016; see also: Human Rights Watch, 22 December 2015).

This ‘cancer in the UN system’ – as termed by Secretary General Ban Ki-moon (Associated Press, 13 August 2015) – has pushed the implementation of a ‘zero tolerance’ policy for such offenses (Sieff, 11 January 2016). Yet UN whistleblower Anders Kompass still originally faced suspension and dismissal for the passing of confidential documents detailing the abuse to authorities in Paris; only earlier this week was he completely exonerated after an internal investigation (Laville, 18 January 2016).

Given the difficulties in exposing such activity – coupled with the fact that many cases likely go unreported – the rate of sexual exploitation and abuse by UN peacekeepers could in reality be much higher (Westcott, 12 January 2016). Figure 2 maps the locations of (known) violence against civilians by peacekeepers in CAR, noting specifically instances of sexual abuse and exploitation. Other conflict actors in CAR are also responsible for gender-based violence (GBV); rates of GBV spiked to over 3 times the average rates seen in the country in 2013 and 2014, in line with the heights of the war (Kishi, 25 February 2015).

However, when sexual violence involves UN peacekeepers it is especially damning given the way it challenges the legitimacy of the peacekeeping mission at large. A recent study by Karim and Beardsley (2016) in the Journal of Peace Research suggests that including a larger proportion of female peacekeepers as well as personnel from countries with better records of gender equality in missions is associated with lower levels of sexual exploitation and abuse allegations. Minimizing these gross human rights violations, especially against populations who are already at risk, is imperative.

This report was originally featured in the January ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.