Rates of foreign direct investment (FDI) to Africa have been increasing (United Nations, 2015). When selecting a location, investors place significant weight on stability – an optimal environment is where stability is high and risk is minimal (African Development Bank, 2012).

The presence of conflict has been found to both have negative effects on FDI inflows, and decrease the likelihood that a state is chosen as an investment location (Li, 2006; Busse and Hefeker, 2007). Both domestic and transnational terrorism may depress FDI (Bandyopadhyay, Sandler, and Younas, 2014). Even the perception of risk of future political violence can have an impact on investment flows (Jensen and Young, 2008).

However, political risk to external investors is different to what it is for citizens, and not all types of violence are indicative of ‘fragility’ or ‘instability’. ‘Political stability’ can be measured as the likelihood that a government will be destabilized or overthrown by unconstitutional or violent means; as such, minimizing this likelihood would have an effect of minimizing destabilization (see Chen, Dollar, and Tang, 2015). As such, certain types of violence – namely, forms of state repression – arguably denote a strong and stable state, as regimes are able to use the resources at its discretion to secure its position, power, and authority. States may use repression as a tactic to enforce their hold on power and to reaffirm their authority, thereby ensuring a form of security (Escriba-Folch, 2013). African regimes often use repression to eradicate competition and subordinate civilian reform and revolt in order to ensure their survival (see Clapham, 1996); intimidating, targeting, and/or killing potential opposition is effective in quelling threats from organized groups (Hafner-Burton, Hyde, and Jablonski, 2010). Creating an environment where armed opposition against the state is minimized can create a climate of reduced instability and uncertainty. Under these circumstances, violence in the form of repression by the state may in fact have the effect of increasing ‘stability’ in that the repression of competitors insures that ‘uncertain’ violence is kept to a minimum.

A new working paper by Kishi, Maggio, and Raleigh finds that investment can impact conflict through ‘incentivizing stability’. Where states are competing for investment, minimizing perceptions and occurrences of instability can have a positive effect on receiving FDI. As such, states have an incentive to repress opponents and civilians to create an illusion of security and control. Therefore, directly and indirectly, investment can incentivize the state to ‘perform’ security differently to secure economic flows. With increased investment, repression may further increase as the loyalties of the state lie with securing the investments within their borders, especially if they are to ensure future investment.

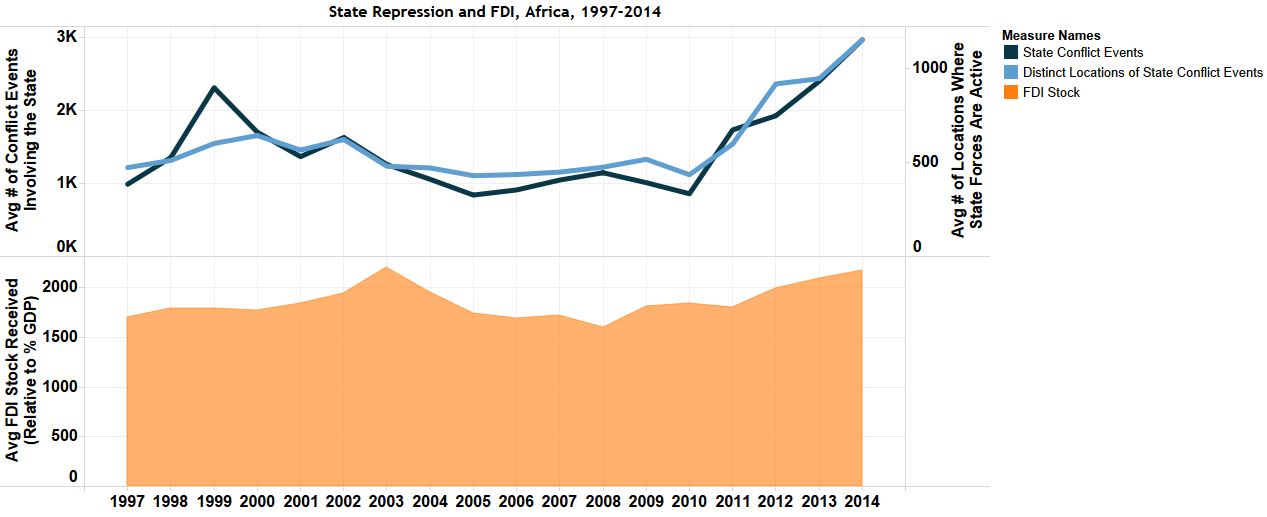

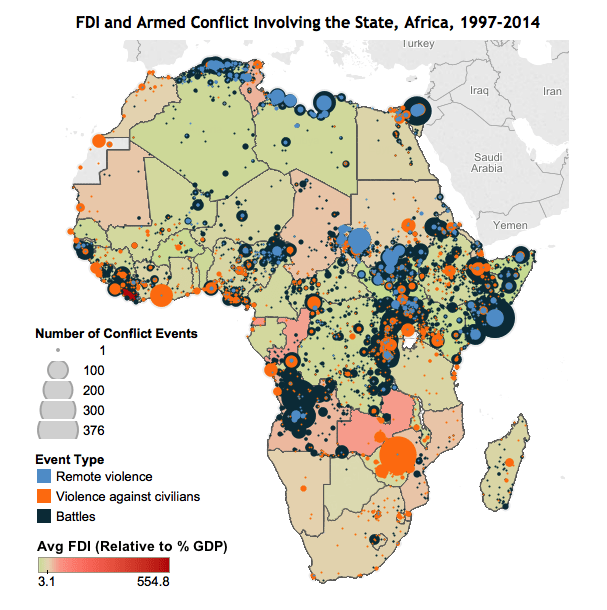

Figure 1 depicts how state repression – both the average number of conflict events involving state forces, and the expansiveness of state forces (measured as the number of distinct locations in which the state is active in conflict) – and the average rate of FDI received by African states have been increasing in tandem, especially in recent years. Figure 2 maps conflict events involving the state between 1997 and 2014 over the average annual rate of FDI stock received by states (relative to their GDP) during the same time period.

There are several recent episodes across Africa that indicate how the relationships between regimes and investors are given primacy to that of the regime and citizens, and that relationship appears to alter how states operate across their own territory.

For example, the 2012 Marikana massacre in South Africa arose from a strike for increased pay by miners at British-owned Lonmin in South Africa. This strike resulted in South African police forces – working in tandem with Lonmin security and the National Union of Mineworkers – firing live ammunition at strikers. Autopsies of the forty dead miners report most were shot in the back, suggesting they were fleeing rather than attacking (Laing, 2012). The incident has since been cited as the most lethal use of force by South African security forces against civilians since the end of apartheid (The Week, 2014).

Another example is the recent Oromo protests in Ethiopia. A string of demonstrations began in late 2015 in response to the Ethiopian government’s ‘master plan’, involving land rights in the Oromia region of Ethiopia. The government sought to expand the borders of the country’s capital into the surrounding rural areas. While the government is legally allowed to do this as it owns all of the land in Ethiopia (Martin and Warner, 2015), the result would be the displacement of many as the region is home to two million people, largely of the Oromo ethnic group (Robins-Early, 2016).

Critics of the plan argue that the ‘land grab’ was in an effort to lease large parcels of land to foreign investors from China, India, and the Middle East (Martin and Warner, 2015). While the government has agreed to scrap the ‘master plan’ (Chala, 2016), the Oromo people continue to demonstrate, arguing they do not trust the authorities (Iaccino, 2016). Despite state claims to the contrary, Ethiopian security forces continue to violently suppress the largely peaceful protests in the Oromia region (Human Rights Watch, 2016). Reports of fatalities suggest that at least 270 have been killed by state forces thus far in the wake of the brutal crackdown on the protests (Iaccino, 2016), being deemed the “worst ethnic violence [in Ethiopia] in years” (Schemm, 2016).

While FDI may be touted for its many benefits to developing countries – it can bring skills and technology that can be used in training a local labor force; it can boost exports and improve the competitiveness and efficiency of local producers; and it can facilitate the expansion of fundamentals to growth, such as public infrastructure (Schoeman, 2015; see also, Rugman and Doh, 2008). It is becoming one of the main sources of capital across Africa, and creating increased competition amongst states to provide the most attractive environments for investors. With minimal accountability to constituencies (see Koenig-Archibugi, 2004; Hunter and Bridgeman, 2008), while being beholden to their investors, these recent examples have made it increasingly apparent where the loyalties of regimes lie.

This report was originally featured in the March ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.