Ethiopia has been subject to a wave of political violence and protest for the past three months. Demonstrations against the Ethiopian government’s ‘Addis Ababa and the Surrounding Oromia Special Zone Integrated Development Plan’ — a program designed to expand the capital, Addis Ababa, into the neighbouring hinterland — is the reason for this unprecedented civil unrest (Africa Confidential, 18 December 2015). Violence against protesters and civilians by security forces accounts for 50% of fatalities in 2016. In spite of the severity of the actions of the security forces, the demonstrators have generally not reacted with violence. Over 90% of recorded demonstrations have involved peaceful protesters.

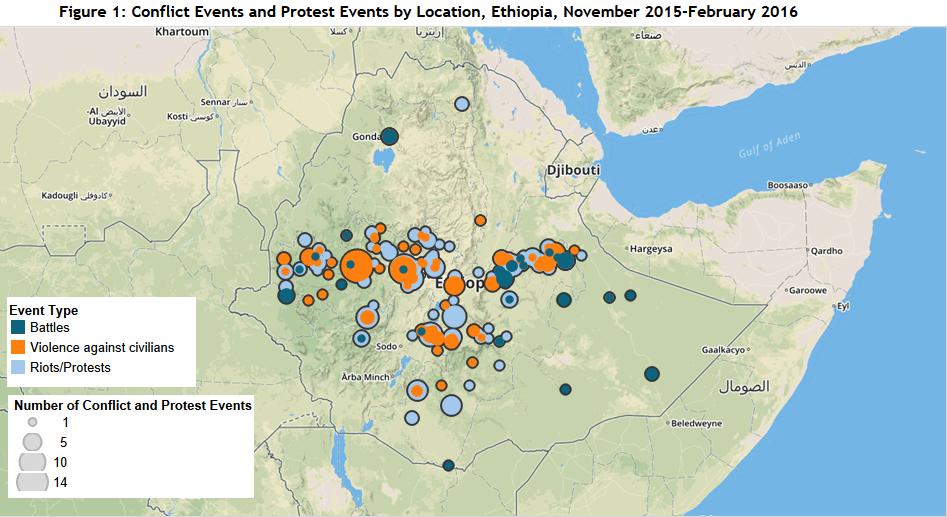

This proposed expansion would come at the expense of the surrounding territory which is currently under the jurisdiction of the Oromo state; this has provoked widespread demonstrations from students and farmers in the Oromo region. The protests started in Ginci where students demonstrated against the sale of Ginci stadium and the clearing of local forest for the proposed expansion (Africa Confidential, 18 December 2015). The protests soon spread to most major towns across the Oromo region (see Figure 1). This in turn spurred a crackdown by security forces.

Political contestation and violence in Ethiopia has generally been limited to clashes, primarily between weakened ethnonational rebel movements such as the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) or Ogaden National Liberation Army (ONLA). These events are 40% and 70% of annual activity for nearly every year between 1999 and 2015 (with the exception of 2006). While these insurgencies can be costly in terms of fatalities, attacks have been sporadic and no insurgent group has mounted a serious challenge to the state.

In contrast, the demonstrations challenge the constitutional arrangement of land, identity and ownership in modern Ethiopia. The 1991 constitution declares land as common property of the nations and nationalities of Ethiopia, in short, no part of the land in Ethiopia belongs to a particular ethnic group though the state owes compensation to the owner of any land seized (Andargie, 2015). Nevertheless, the scale and distribution of the protests across the Oromo region (see Figure 3) and the composition of the protesters (primarily Oromo students and farmers) has shown the state that much of the public feels differently.

In spite of attempts to cast the protesters as terrorists or agents of the OLF, the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) and its local Oromo coalition partner, the Oromo People’s Democratic Organization (OPDO), have had to acquiesce to the demonstrators demands and cancel the Masterplan (HRW, 2016; BBC News, 13 January 2016). OPDO has often been perceived as a tool of indirect rule through which the EPRDF can impose its will on Ethiopia’s most populous region (Gudina, 2007). However, these protests may reverse this relationship with OPDO operating as an intermediary between the government and the Oromo people.

This report was originally featured in the March ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.