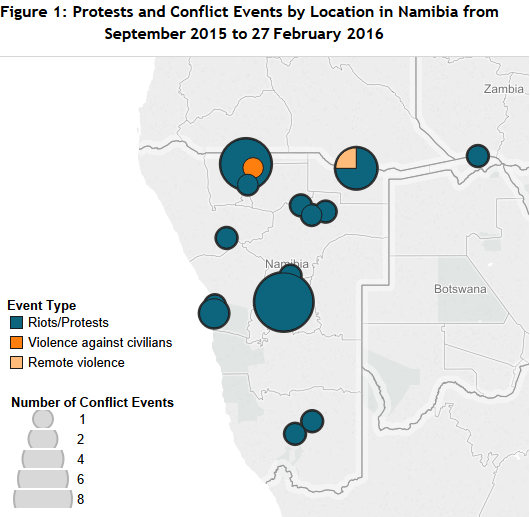

Over the past six months, Namibia has seen an above average number of riots and protests. The relatively peaceful country generally sees a combined average of 6.5 riots and protests per month (just over 4.5 protests and 2 riots per month). However, there were 13 protests in October, 5 protests and 6 riots in November, and 4 protests and 4 riots in January (see Figure 1). The increase in riots can be attributed to the Children of the Liberation Struggle (CLS), commonly referred to as the ‘struggle kids’.

In October and early November 2015, CLS members held protests in Katura and the capital Windhoek, demanding jobs with government agencies (see Figure 1). In mid-November, CLS members in Eros tried to strangle a staff member of the Namibian Exile Kids Association (The Namibian, 26 November 2008). In the northern Oshana Region, CLS blocked South West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO) offices and destroyed water meters in Oshakati, clashed with police in Okandjengedi, and injured one policeman at a rally. Prior to November, CLS had not reportedly been involved in a riot since August 2014.

Riots continued on 15 – 16 January, as CLS members attacked a farmer with a machete; the farmer fired back, injuring four (The Namibian, 17 January 2016). On the same day, struggle kids rioted at the Brakwater settlement in Windhoek, demanding relocation; 400 members of the group were moved to Brakwater in October (Namibian Sun, 8 January 2016). Rioters attacked civilians with panga knives, while Special Reserve Forces fired tear gas and rubber bullets.

Since 2008, approximately 500 of the 8,000 registered struggle kids (now adults) have protested for employment and assistance from the SWAPO-led government (SWAPO Party, 2011). CLS claim a special responsibility is owed because they were raised abroad and forced to repatriate ‘home’ to a Namibian culture of which they knew little. Reports mention that CLS protesters often appear under the age of twenty, meaning they were not born in exile before independence and, therefore, claims to special treatment are groundless. Regardless, recent activity of CLS embodies many of the country’s tensions regarding land and employment for all young Namibians.

Although one of the least densely populated countries, spanning over 825,000 square kilometres, Namibia’s protests often involve land rights by farmers who are dependent on agricultural subsistence living. Though the country has strong mining, fishing, and tourism markets, it also has one of the highest income inequality rates in the world. In the past six months, employees have protested for improved pay and working conditions in nine of Namibia’s 14 regions (see Figure 6).

As of the 27 February, Namibia witnessed a decrease in both conflict events and protests. However, even if CLS activity dissipates, similar grievances by other citizens are not likely to disappear without changes in government policies. President Hage Geingob has asked all youth to be patient, “including both the struggle children and those who were not in exile but are also children of those who fought against apartheid inside the country” (SWAPO Party, February 2013).

This report was originally featured in the March ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.