The first two months of 2016 saw an unprecedented spike in protest activity in Tunisia. The number of riots and protests recorded by ACLED in January has been the highest since the 2011 uprisings, while mobilisation continued at slightly diminished levels in February. The epicentre of the unrest was the western province of Kasserine, where the self-immolation of a young unemployed in the capital city triggered violent protests across the region (International Business Times, 29 January 2016). Protests quickly spread to the rest of the country, involving the traditionally turbulent peripheries of Tunis and the southern regions along with the more quiet coastal provinces of Bizerte and Monastir. A police officer died during clashes in the town of Feriana, while at least 100 people among officers and protesters reported injuries.

The revolts vividly reveal the popular dissatisfaction over the outcome of the revolution, especially among the younger generations (Africa Confidential, 19 February 2016). The youth unemployment rate is estimated at 30%, and there is little hope that economic trends will improve considerably in the near future. For their part, the people of Kasserine have long denounced systematic marginalisation and growing regional inequalities (Inkyfada, 13 July 2015). The government, led by old allies of former presidents Ben Ali and Bourguiba and crippled by internal divisions, seems thus unable to meet the widespread desire for political and social change.

Tunisia is also facing the continuous threat of Islamist insurgency on its territory. Since the attacks on a tourist resort in Sousse last summer and on a military convoy in central Tunis in November, the government has stepped security measures all over the country. In February only, the army killed four militants in three separate clashes in the provinces of Kasserine and Gabes, whereas a civilian bystander died when caught in a crossfire between military forces and gunmen near Jendouba. Last month, concerned with the possible spillover of insecurity, the government also completed a barrier along the border with Libya (Al Jazeera, 7 February 2016). The defence system, which consists of sand banks and moats and extends for 200 km from Ras Ajdir to Dehiba, aims mainly at fending off Islamist militants returning from training camps in neighbouring Libya.

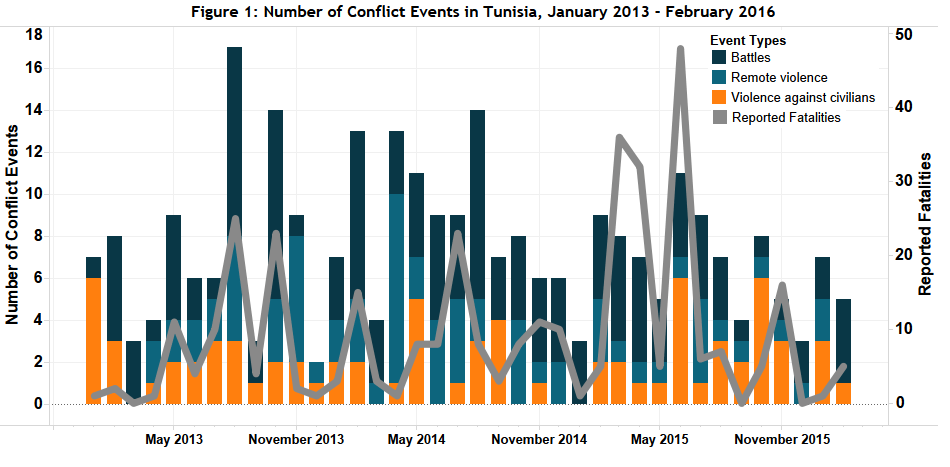

Data show that conflict activity in Tunisia has been constantly decreasing since 2013 (see Figure 1). Organised in smaller cells and severely restrained in their operational capacities, armed Islamists are mainly active in the mountainous territories of central and western Tunisia. Although they retain the ability to launch resounding, lethal strikes against civilians and security forces, Islamist militias appear no longer able to engage in insurgent campaigns on a larger scale. The recent wave of protests show nonetheless that the prioritisation of security may have come at the expense of inclusive and well-balanced development.

This report was originally featured in the March ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.