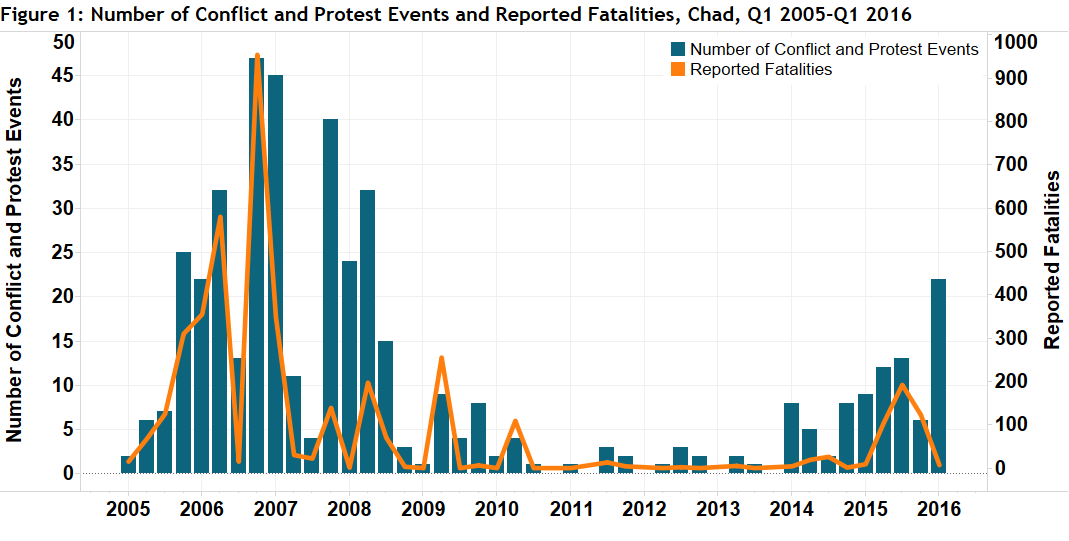

Chad witnessed an increase in domestic protest in early 2016. This spike in political unrest represents a distinct departure in what has been a consistently low activity country from 2010 onwards (see Figure 1). A low level of political violence and unrest can be at least partially attributed to the thawing of relations between Presidents Idriss Deby (Chad) and Omar Al-Bashir (Sudan); the latter of whom previously sponsored rebel and Janjaweed incursions into Chadian territory during the mid to late 2000s (Lewis, 11 February 2010). While previous spikes of political violence have occurred in Chad due to incursions of external actors – Boko Haram in mid-2015, the Janjaweed in mid-2000s, multiple rebel groups in 2006 and 2008 – this recent wave of protest represents a change as the threat to Deby is both peaceful and domestic (Human Rights Watch, 2006; BBC News, 2008).

The first protests in February began when unemployed graduates held a sit-in demanding jobs in the civil service (Africa News, 8 February 2016). The violent suppression of the demonstrations by the police force prompted denunciations by opposition parties and further protests (ibid.). Anti-government sentiment was galvanised in mid-February, when a video showing the gang rape of a young woman by the sons of several leading officials was circulated online (Reliefweb, 11 March 2016). After the video circulated, protests and shutdowns launched under the banner of ‘Enough is Enough’ brought N’djamena, Moundou, Abeche, Largeau and Sarh to a standstill (Reliefweb, 28 February 2016). The protests endured, and in fact grew, after security forces killed a demonstrator in N’djamena, indicating that repression may not be sufficient to quell rising discontent with the incumbent regime.

Historically, protests and riots have been very rare in Chad, representing just 9% of recorded events in the ACLED dataset for that state, as opposed to a country-continental average of 26%. This lack of protest has been matched by a lack of political engagement by much of the public. The turnout for the 2006 and 2001 elections were incredibly low and boycotted by the opposition (BBC News, 2006; Reuters, 28 April 2011). Similarly, Deby was able in 2004 to amend the constitution to remove the two-term limit on presidential tenure without provoking public outrage, a marked contrast to the recent examples of Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo and Burkina Faso (Crisis ACLED, 23 June 2015; Reliefweb, 23 January 2016). Instead the amendment helped lay the foundation for the Second Chadian War in 2005, but opposition came from rebels guided by Sudan and former insiders of the Deby regime, not the public at large (Hicks, 24 March 2016).

March saw fewer protest events and Deby is still predicted to win the April elections (Reliefweb, 23 January 2016). Nevertheless, the demonstrations represent a departure from the political status quo.

This report was originally featured in the April ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.