Recent analyses on Libya point to the potentially destabilising effects of a possible international intervention led by France, the United Kingdom, Italy and other regional powers. The race to liberate Sirte, seized by the Islamic State in February 2015, pits the rival domestic administrations and their respective fighting factions based in Tobruk and Tripoli. Official UN reports and media coverage has provided extensive evidence of external interference on both sides, reflecting the wider regional implications of the Libyan conflict (Reuters, 24 February 2016; United Nations Security Council, 9 March 2016; ; The Guardian, 1 June 2016).

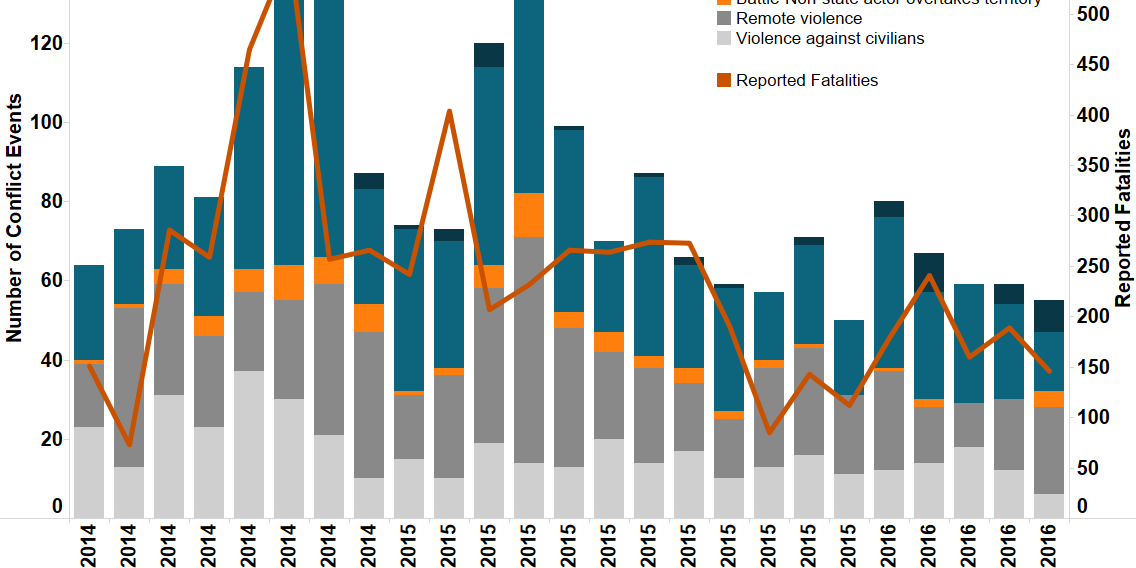

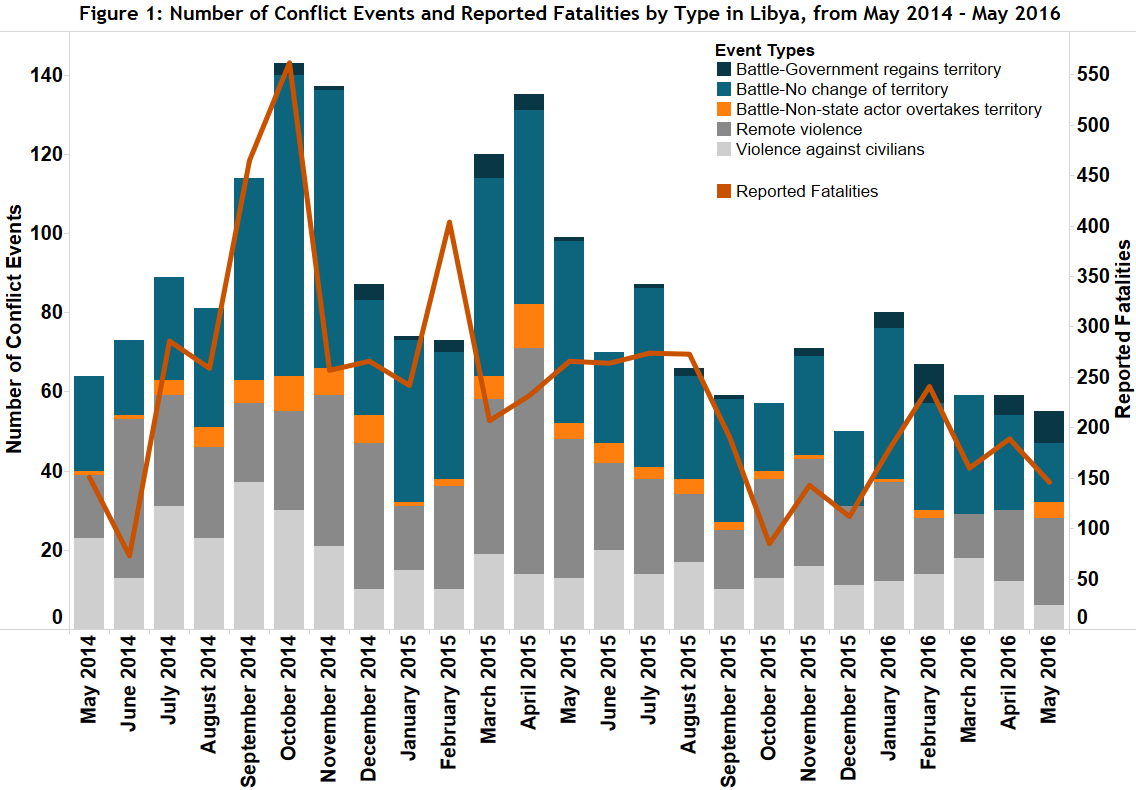

A general overview of Libyan conflict dynamics since the outbreak of war in May 2014 reveals a pattern of relative stability over the past year (see Figure 1). Whilst government forces have regained control of an increasing number of locations in 2016, these shifts have not translated into dramatic changes in the level of overall political violence and related fatalities. Upon closer examination, agents of political violence up to May 2016 suggest that Libya is entering into a transition stage in which splintered political groups are beginning to coalesce, shifting the balance of power back towards a bipolar conflict system.

Two recent developments in Libya support the hypothesis of stabilisation: the first is the increase in the number of discrete military forces and successful battles in which territory has been ceded to government forces, the second is the increase in low-level political militia activity contained within Tripoli, suggesting an attempt by armed brigades to be ‘bought in’ to the emerging political settlement. Taken together, these dynamics reveal – contrary to speculation – that political forces on the ground have taken steps to mitigate against further fragmentation in the coming months.

New Military Operations to Regain Territory

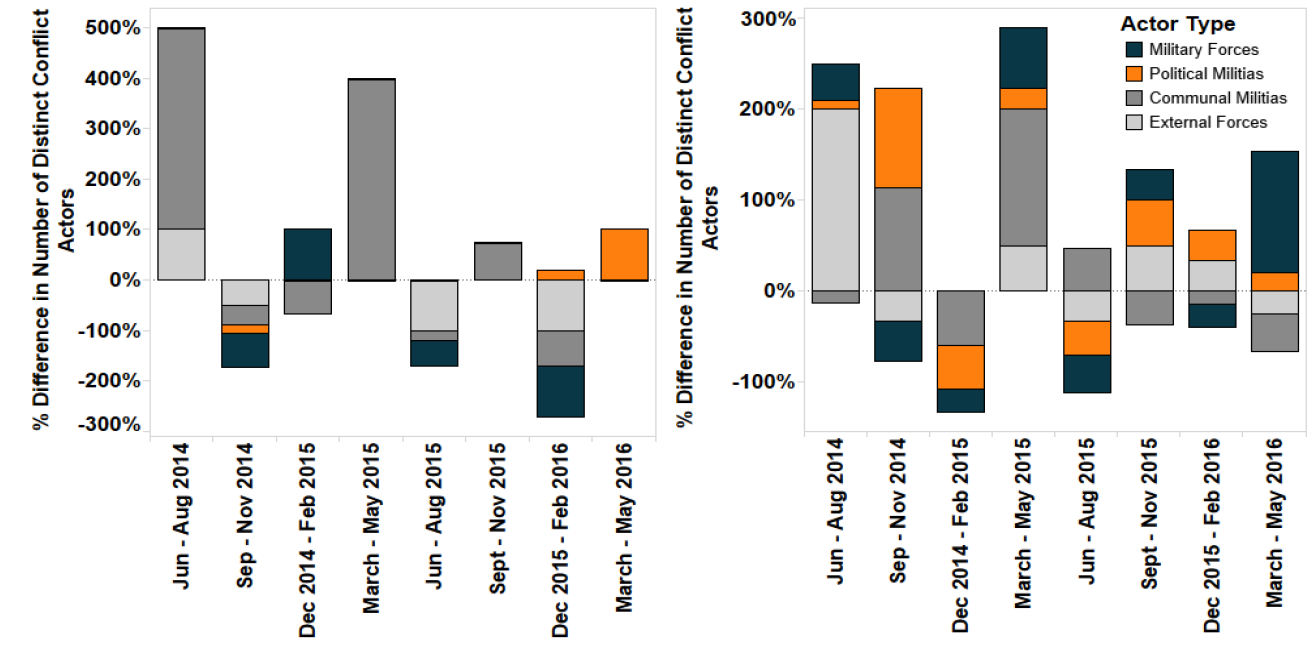

The defeat of IS and the liberation of Sirte is a major source of competition between General Khalifa Haftar’s Libya National Army (LNA) forces and militias from Misrata (the latter now operating under the new umbrella of the General National Accord, or GNA): who takes Sirte first will take spoils and symbolic legitimacy (The Economist, 14 May 2016). Commentators have argued that this internal competition could lead to further fragmentation of the already-unstable political alliances that currently exist, which would undermine the functioning of the Tripoli-based unity government (The Big Story, 6 May 2016). Without ignoring the potential for escalation that the offensive in Sirte against Islamic State militants poses, Figure 2 shows the percent change in the number of discrete actors operating in Libya.

Figure 2: Change in Number of Actors in Tripoli (left) and Libya (right) by Actor Type, from June 2014 – May 2016

Two trends are clear: first, in the period from March – May 2016, new military formations were created across the whole of the Libyan territory, reflecting the push by the GNA government to consolidate power into a formalised army structure. This attempted consolidation led to the creation of a Presidential Guard, tasked with securing vital institutions for the GNA as it installed itself in Tripoli. Second, this consolidation led to the establishment of the Operations Room Bunyan Marsous (Solid Structure) resulting in a dramatic increase in successful territorial confrontations in May 2016 as the forces supporting the unity government carried out a military assault to liberate Sirte from Islamic State control. Whilst operating as a de facto military force, the fighting groups that support the GNA are comprised of militias predominantly from Misrata and Al-Jufra who are further supported by — but not integrated with — the Petroleum Facilities Guards (PFG) commanded by Ibrahim Jadhran (Financial Times, 6 April 2016). By contrast, the rate at which new political militias engaged in the conflict between March – May 2016 was lower than the two periods from September 2015 – February 2016 (see Figure 2). This evidence might suggest that local militias’ interests are moving away from the control of power in peripheral territories and towards Tripoli as the major centre of power.

Political Militias in Tripoli

The second trend is the increase in the number of political militia groups activating in the capital, Tripoli, following the signing of the Libyan Peace Agreement (LPA) on 17 December 2015 (see Figure 2). The LPA paved the way for the formation of the UN-backed national unity government, headed by Prime Minister Fayez al-Sarraj. The number of militia groups from December 2015 – February 2016 increased by 20%, followed by a further 100% increase from March – May 2016. This second escalation of militia activity is particularly pertinent given that it coincides with the arrival of the Presidency Council in Tripoli on 30 March.

This emerging conflict pattern is largely localised to Tripoli and has been characterised by street battles between rival militia groups and increased rates of kidnappings and murders. Perpetrators of the violence include the Bab al-Tajoura Brigade, the Tripoli Revolutionaries Brigade, the Abu Salim Brigade and the National Mobile Forces. Militia violence may indicate the desire of these armed groups to be included in the latest political settlement: as al-Sarraj works to build a unified military force and international powers vote to lift the arms embargo, these flash episodes of conflict signal to the necessity of their inclusion for enduring stability. The defeat of the Islamic State, as well as the preservation of Libya’s territorial unity, thus hinge on the emergence of an inclusive political settlement orientated to reconciling the several warring factions and avoiding the mistakes made under the political arrangement of 2012-2014.

This report was originally featured in the June ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.

Authors: James Moody, Andrea Carboni, and Giuseppe Maggio