We are often asked about our sources and source methodology that underlies our conflict data, analysis, and mapping. In this special focus, we discuss our local violence monitoring choices, decisions, and trajectories. Information about sourcing in general is provided in a separate paper from 2015 available here. ACLED sources conflict data from multiple sources: it is “part of a growing number of research projects in social science to use the current benefits of global online media and information to disaggregate and track social phenomena. Through monitoring reports from multiple sources in multiple countries, datasets such as ACLED can move beyond the highly aggregated binary approach of classifying political violence seen in earlier studies and breakdown conflicts into a series of spatially and temporally discrete events (Gleditsch et al., 2013)” (Wigmore-Shepherd, 2015). In addition to media, ACLED relies on a range of other sources as well to capture conflict and protest events, including local newspapers, online journals, and reports by humanitarian organizations.

Relying on media monitoring, however, raises challenges. Datasets relying on external sources are subject to the biases of their sources. Sources can introduce bias through both (1) selective reporting – e.g. choosing to report only certain types of events, or only reporting events involving certain actors – and/or through (2) omission – e.g. lacking the capacity to report events occurring in certain areas or regions. These biases can pose a serious risk to the validity of data.

Complementing information from online media with reports from local conflict and violence monitors on the ground within countries can have advantages. Certain types of violence – especially those types that are often not captured at the macro-level by online media – can be captured by local sourcing initiatives. Local sourcing can also be especially helpful during periods or environments of media blackout where information from global online media might be limited. Local sourcing is especially important and useful in: areas where the access of the international community is restricted (e.g. Somalia); countries with closed media environments (e.g. Ethiopia, Eritrea); countries with areas that are difficult to access (e.g. FATA area of Pakistan); and conflicts in which many small-scale events (instead of large-scale events) comprise the crisis, as media sources at the macro-level often do not report on such events (e.g. Burundi).

In Burundi, where there is a ‘media blackout’ (International Media Support, 2015; Nkengurutse, 2015), and “persecution of the media has been constant” since early 2015 (Reporters Without Borders, 2016) following the failed coup attempt in response to President Nkurunziza’s decision to seek a third-term, reports from global online media are limited. Further, the Burundi Crisis has increasingly been comprised of smaller scale events (such as arrests, home searches, and border stoppings), and it has diffused away from the capital Bujumbura as the crisis has continued, which has meant that local conflict monitoring has been especially advantageous in coverage of the Burundi Crisis (see: ACLED’s Burundi Crisis Local-Level Dataset).

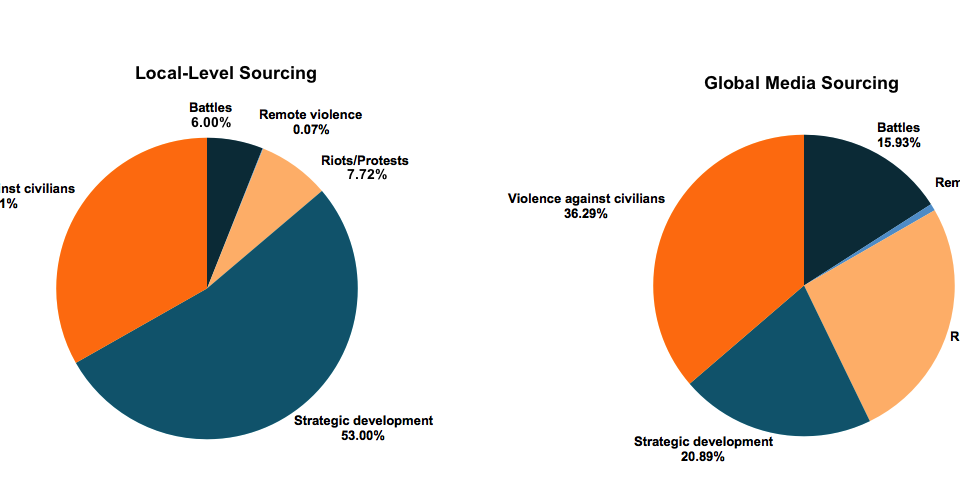

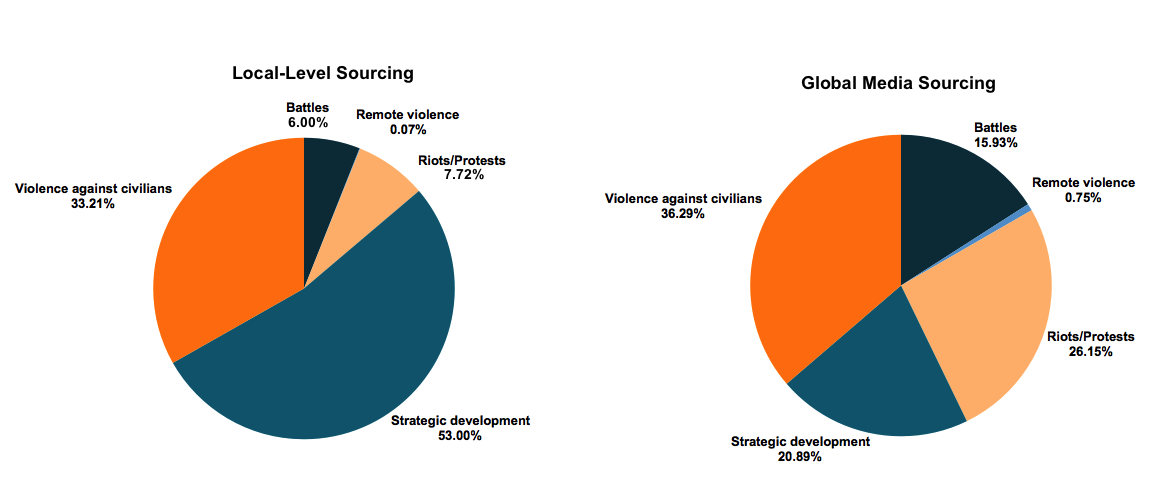

Figure 1 depicts the differences in the types of events captured by online media sources versus local sources during the course of the first year of the Burundi Crisis. Local-level sourcing identifies large rates of ‘strategic developments’, which are largely arrests (arbitrary or otherwise), home searches, and (at times, violent) border stoppings, which have become fixtures of the current conflict dynamics (see: ACLED, 2016). These types of ‘small scale’ events are not often captured by global online media sources at the macro scale.

Figure 1: Data Source Differences, Burundi Crisis by Event Type, 26 April 2015 – 25 April 2016

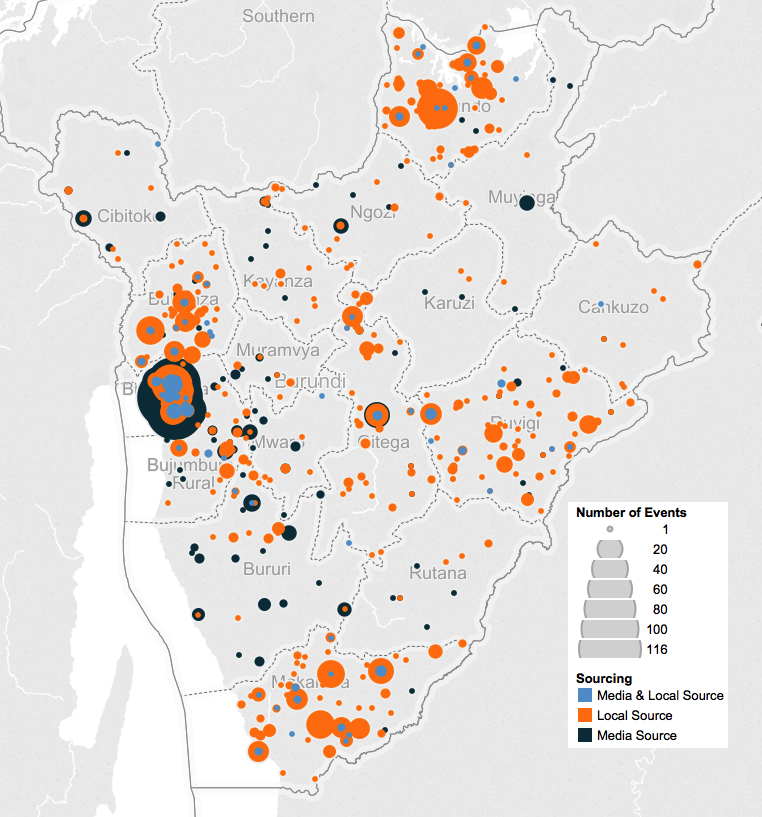

Figure 2 depicts the differences in the regional coverage of events captured by global online media sources versus local sources during the course of the first year of the Burundi Crisis. While online media sources capture events occurring in and around the capital of Bujumbura, the capacity of these sources to report in more remote areas is more limited. Local sources are able to shed light on conflict trends occurring in other regions of the country.

Figure 2: Data Source Differences, Burundi Crisis by Event Location, 26 April 2015 – 25 April 2016

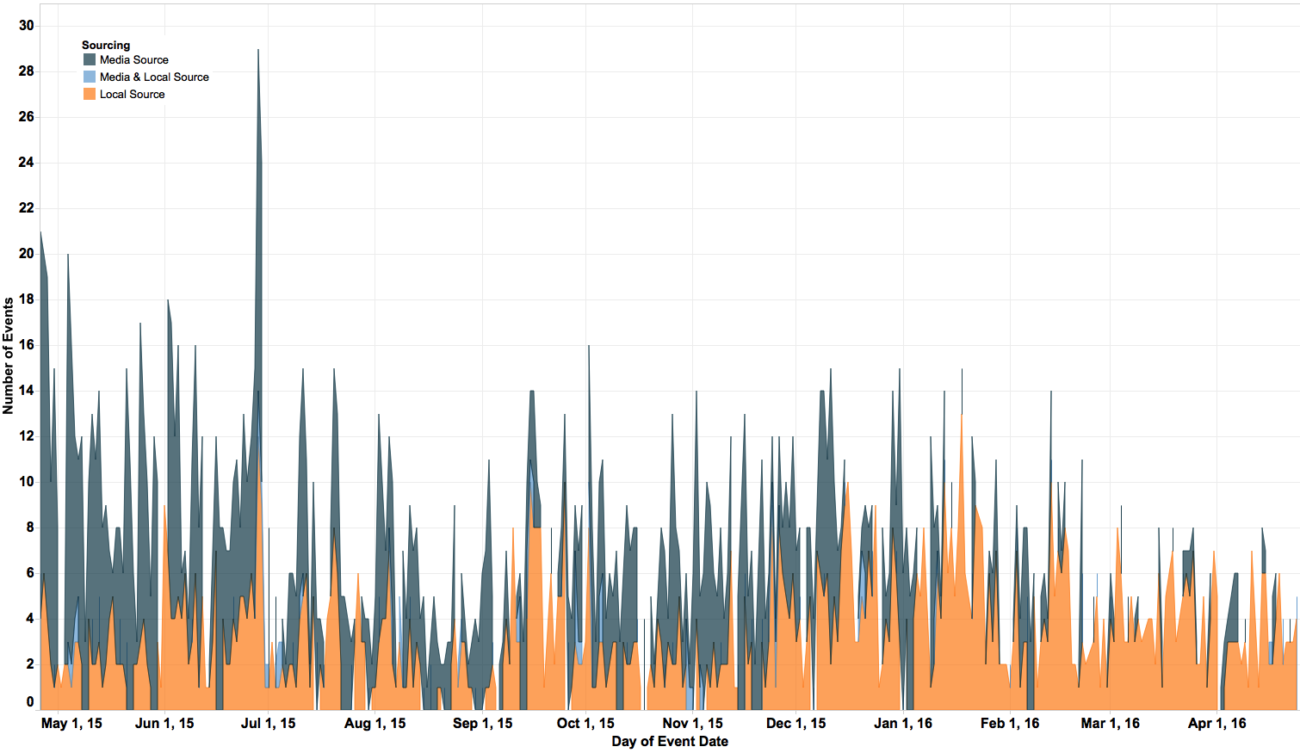

Figure 3 depicts the differences in the coverage of events captured by online media sources versus local sources during the course of the first year of the Burundi Crisis. While global online media sources were able to cover a great deal of activity near the start of the crisis in early 2015, as the crisis has continued, local sourcing has played an increasingly larger role as a result of: (1) the media blackout, and the fact that the access of the international community has been severely curtailed as the crisis has progressed; (2) the diffusion of events away from the capital to more remote parts of the country; and (3) while the crisis began with large-scale demonstrations and repression, which were covered more readily by online media, the crisis has largely become comprised of smaller scale events (such as arbitrary arrests, home searches, and border stoppings), which online media sources often do not and are unable to capture.

Figure 3: Data Source Differences, Burundi Crisis Temporal Trends, 26 April 2015 – 25 April 2016

There are a number of ways in which datasets can incorporate local sources, especially as projects may differ with respect to coverage of regions, issues, etc. Local incident monitoring projects within countries – such as ‘crowdseeding’ efforts, where local, trained citizen journalists report incidents directly (for example, see: Van der Windt and Humphreys, 2014) – already exist within many countries. These organizations may establish partnerships to supply on the ground data. Information from local newspapers could also be integrated into coding schema, to complement information from online media sources. Crowdsourcing – such as relying on local populations to report incidents via texts/SMS, tweets, etc. – could also be used, though it is less reliable than the former two strategies given the lack of oversight involved. In many of the countries on which ACLED reports, local-level information has been sought to complement online media reports through reliance on local media (such as local newspapers and radio) and the establishment of partnerships with local conflict monitors. As a preference, ACLED partners with local organizations that have incident monitoring in place already, as is the case in ACLED’s current Burundi Crisis Local-Level Dataset initiative.

However, while local sourcing offers an important and distinct view of what may be happening at the local-level, local sourcing comes with its own inherent challenges. This includes needing to: account for biases, determine the sustainability of local projects, implement triangulation methods, and address ethical concerns.

ACLED’s goal is to create an effective and useful cross-country, cross-conflict data system. Establishing partnerships with local organizations in which standardization is prioritized is crucial in this endeavor. In order to be able to make cross-country and cross-conflict comparisons, it is important that local-level information that is reported can fit into the framework for what ACLED has established for cross-country, cross-conflict monitoring. Having clear definitions of what constitutes separate events is crucial in order to recognize what comprises political risk and violence according to data providers. Parsimony is key, and identifying what can be committed to being recorded systematically is imperative. When partnering with local monitoring initiatives, ACLED identifies and isolates which reported events can be standardized for cross-country, cross-conflict contexts; only these events are integrated, as only they can subsequently be used for effective comparisons across contexts.

While local sourcing may offer many benefits, not all conflict environments require or need to rely on a local-level view in order to capture conflict trends occurring on the ground. While local sourcing may offer benefits, the value-added may not necessarily always justify the resources needed to establish and sustain these types of partnerships. Countries with open media environments can often produce sufficient, reliable, and multi-sourced information that limits the added value of a local-level incident monitoring system (e.g. Nigeria). Countries with robust radio systems specifically designed to monitor and alert about political issues and violence can often be an effective alternative to incident monitoring as well, such as DR-Congo’s Radio Okapi, Sudan’s Radio Dbanga, or the Central African Republic’s Radio Ndeke Luka.

For more on ACLED’s coverage of the Burundi Crisis using information obtained through a partnership with a local conflict monitoring initiative, see ACLED’s Crisis Blog. New local-level conflict and protest data are available there weekly.

This report was originally featured in the June ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.