In May 2016, the number of battles and conflict events in South Sudan fell to the lowest level in the past 12 months (see Figure 1). The decrease in total events and battles is due, in part, to the formation of a transitional government and the reinstatement of opposition leader Riek Machar as First Vice President on 26 April. In hopes of ending a civil war that began in December 2013, South Sudan’s President Salva Kiir and Machar’s Sudanese People’s Liberation Army/Movement-In Opposition (SPLA/M-IO) signed a peace agreement on 26 August 2015, with a provision calling for a transitional government to be formed within 90 days. Despite an overall decline in armed confrontations, a number of discernible trends are apparent. First, the geography of battles has shifted west to areas previously unaffected by conflict, riots and protests increased throughout May, and civilian-targeted violence persisted.

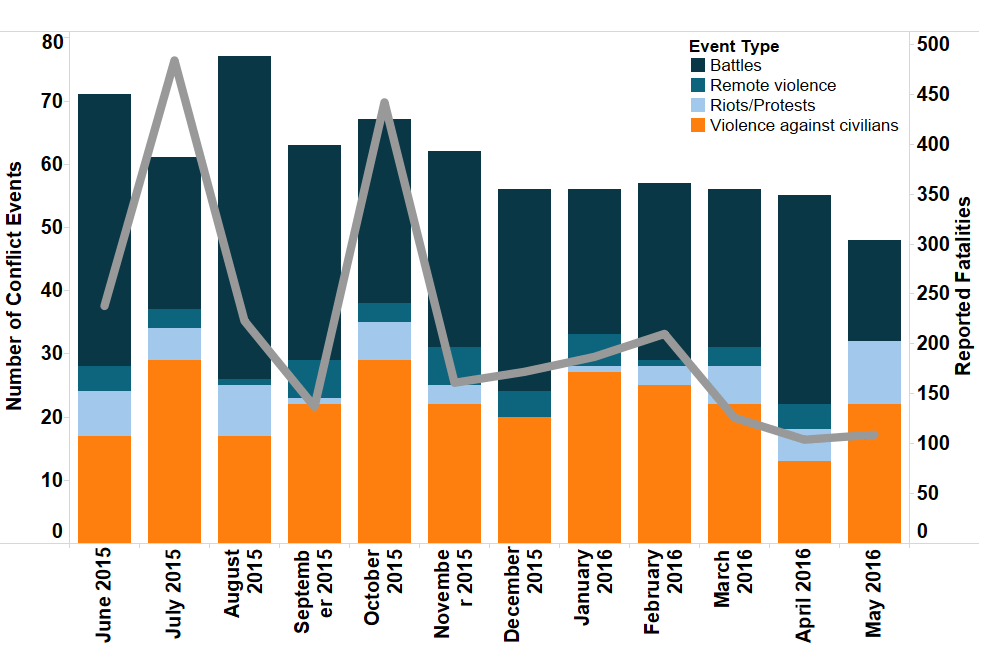

Figure 1: Number of Conflict and Protest Events by Type and Reported Fatalities in South Sudan, from June 2015 – May 2016

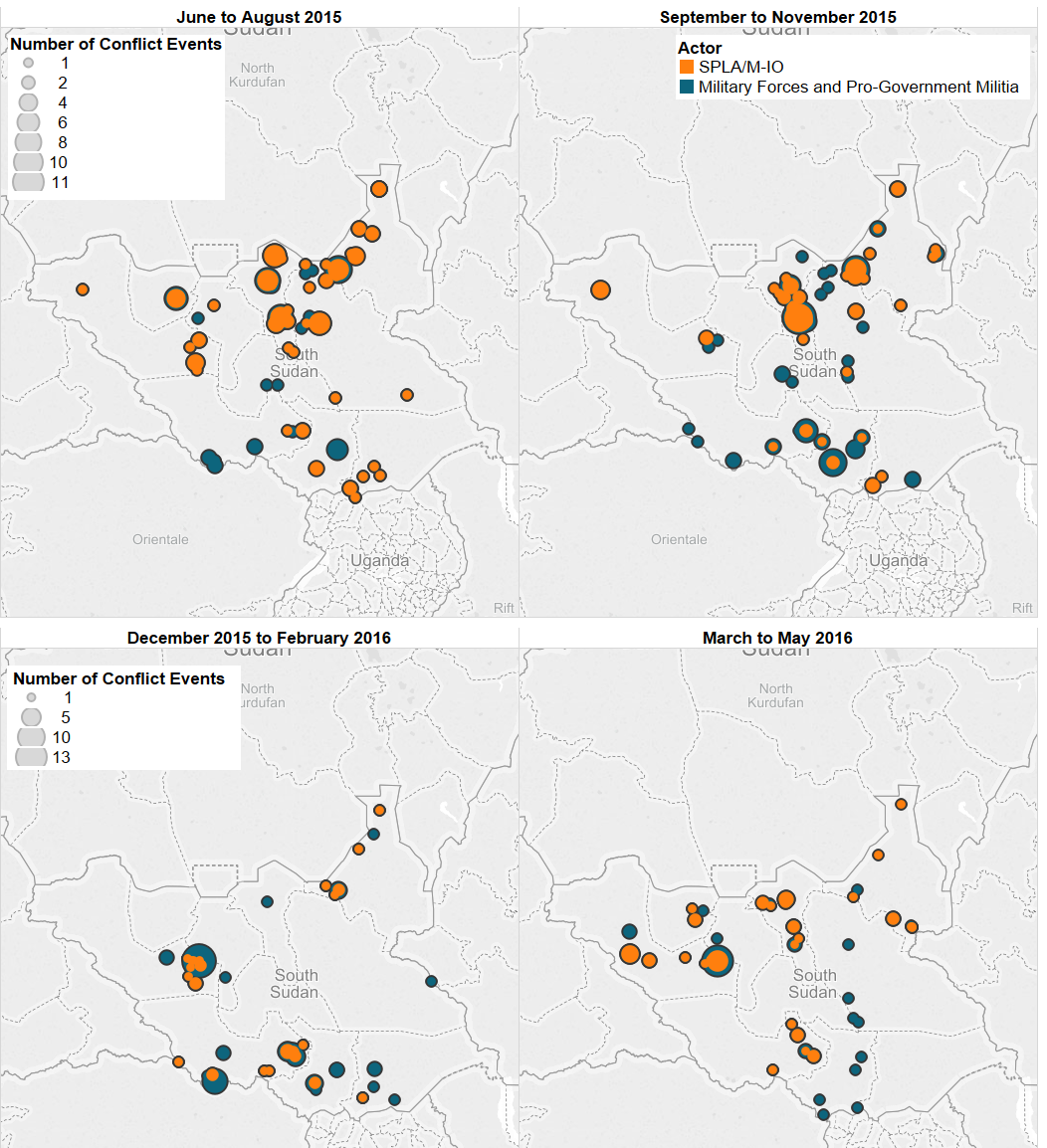

From June through November 2015, conflict events involving military troops (predominantly of the Dinka ethnic group) and SPLM/A-IO forces (predominantly Nuer) primarily took place in the oil-rich states of Unity and Upper Nile (see Figure 2). However, since December, the geography of conflict has shifted further west, with clashes taking place in the previously uncontested areas of Western Equatoria and Western Bahr el Ghazal, including battles throughout Wau and Raga Counties in May (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Number of Conflict Events Involving Military Forces and SPLA/M-IO by Location in South Sudan, from June 2015 – May 2016

Despite a decrease in battles and remote violence, May saw the highest number of riots and protests since August 2015 (see Figure 1). On 28 May, Dinka youth protested in Juba, calling for the resignation of an archbishop who had invited Machar (an ethnic Nuer) to attend church services. While Machar urged church members to reconcile the bloodshed of the past, Dinka protesters later accused church leadership of “inviting the enemy” (Radio Tamazuj, 24 May 2016; Sudan Tribune, 30 May 2016). Violence against civilians also continued at a steady rate in South Sudan, with 22 such incidences in May (see Figure 1). The majority of events targeting civilians are committed by unidentified armed groups, Murle ethnic militia (restricted to Jonglei State), and military forces.

The initial decrease in conflict events, particularly battles, following the creation of the transitional government may be short-lived. The country experienced a similar decrease in conflict events and battles in September 2015 following the signing of the peace agreement, only to see a spike in violence against civilians and reported fatalities in October (see Figure 1). Some news outlets report that violence is continuing at a steady rate despite Machar’s return to Juba. However, such reports consider criminal behaviour to be a chief source of violent activity, including armed elements “interfering” with World Food Programme aid convoys (Radio France Internationale, 1 June 2016).

A key issue to be addressed by the newly formed transitional government is Kiir’s proposal to create 28 states from the existing 10 states. The unilateral decree was announced in October 2015, and new governors appointed in December. Kiir recently agreed to allow a committee to review the borders of the 28 new states, but not to consider a reversal of the decree (Radio Tamazuj, 2 June 2016). August’s peace agreement is based on a proposed system of power-sharing of the existing 10 states, not 28 ethnically-divided states. Therefore, the success of the new transitional government critically depends upon how many states will be governed. Governors suspected of supporting rebel groups are dismissed or suspended (Human Rights Watch, 6 March 2016). A failure to resolve the issue of state boundaries will potentially lead to continued fighting between government and opposition forces, despite the reunification in Juba.

Machar’s willingness to reunite with the government has also led to divisions with those once loyal to the opposition, notably including General Peter Gadet. Splits in the opposition may led to battles between reunified military troops and opposition factions that are angered by Machar’s growing relationship with the government. As Kiir and Machar rebuild an effective working relationship, the success of the transitional government also depends upon its ability to manage bureaucratic tasks, such as tax collection and paved roads. The world’s youngest country has “long been driven by personalities, not policies” (New York Times, 30 May 2016). But the government now needs to address issues of infrastructure and economy in order to prevent societal grievances from bubbling up into riots and violence. Therefore, the political reconciliation of Kiir and Machar must not only trickle down into an ethnic reconciliation within society. It must also catalyse a stable economy that is not controlled by internal power struggles within the government (New York Times, 30 May 2016).

With a lot on the shared plate for Kiir and Machar, it will be seen in the coming months whether the return of South Sudan’s “original political odd couple” will bring about a return to peace and stability in South Sudan – politically, ethnically, and economically (World Politics Review, 9 May 2016).

This report was originally featured in the June ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.