Levels of political violence dropped to the lowest levels witnessed this year since reaching a high point in April 2016 (see Figure 1).

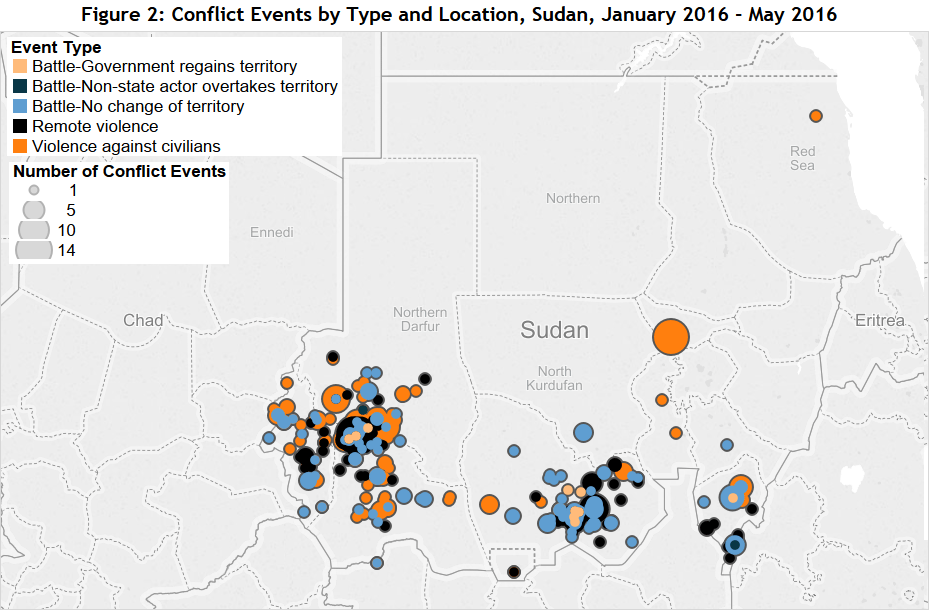

The spike in conflict in March and April was driven by the escalation of the conflict in South Kordofan between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Sudanese Peoples Liberation Movement – North (SPLM-N). Peace talks between the government and the rebels failed in December after the SPLM-N accused state forces of attacking their positions during the negotiations (Nuba Reports, 5 December 2015). The two parties disagreed over the nature of the dialogue, with the government maintaining that the objective of the talks is to settle the conflict in South Kordofan and Blue Nile, while the SPLM-N has called for a more holistic approach to resolve the multiple conflicts Khartoum has with its peripheral regions (Sudan Tribune, 30 April 2016). In response, the government launched a heavy offensive on the rebel-held areas of Um Sediba, Al-Maradis, El Lipo, Kutna, Ugab, Karkakaia, and El-Bir in March, though reports differ over whether the offensive resulted in the government securing territory (see Figure 2) (Sudan Tribune, 30 April 2016).

However, May witnessed a dramatic drop primarily in South Kordofan. This may be because Sudan is beginning to enter the wet season where mobility is severely reduced, limiting the ability of armed actors to move the weapons and vehicles necessary for an armed campaign. Sudan has witnessed similar slumps in levels of political violence from early summer to December, typically after a spike in violence (see Figure 1). In the run up to the rainy season the government and the rebels typically intensify their operations in order to secure key areas before the rain makes movement difficult (Strategy Page, 2016).

The rains do not only affect ground operations but also limit the government’s aerial bombing campaign (Nuba Reports, 4 November 2013). The use of barrel bombs against rebel-held areas is a key pillar in the government’s fight against the SPLM-N with instances of remote violence accounting for between 36% and 59% of violent conflict events since February 2016. Aerial bombing event frequency halved between April and May, potentially and additionally due to Sudan’s current thawing of relations with the West, particularly the European Union which perceives Khartoum as a key ally in stemming the current migrant crisis (Africa Confidential, 4 December 2015). However, the government’s bombing campaign has threatened to destabilise this rapprochement with the high profile killing of six children in Heiban by a government bomber at the very beginning of May. The act drew widespread condemnation from the ‘Troika’ (Norway, the United Kingdom and United States) (Radio Dabanga, 29 May 2016). With the onset of the rains limiting the danger of the SPLM-N, the government may use the next few months as a key moment to ease its bombing campaign in order to ease aid its relationship with Europe.

Lastly, the SPLM-N along with the rebel Sudan Liberation Movement led by Minni Minnawi (SLM-MM) offered a ceasefire in late April in order to facilitate negotiations (Radio Dabanga, 29 April 2016). This combination of factors has created a situation in which the main belligerents of the conflict have reduced their means for perpetuating conflict and have a vested interest to reducing hostilities.

In contrast, the Darfur region has seen a consistent decrease in conflict since January 2016 (see Figure 1). In spite of the presence of government-backed ceasefire, January witnessed high levels of political violence in the form of battles between the military and the Sudan Liberation Movement led by Abdel Wahid al Nur (SLM-AW) (Sudan Tribune, 16 January 2016). These battles, along with a campaign of aerial bombardments, have been primarily concentrated in the rebel group’s stronghold in Jebel Marra in the centre of the Darfur region (see Figure 2). While the government initiated ceasefire proved to be ineffective in limiting the clashes between itself and the SLM-AW and SPLM-N, the rebel-initiated ceasefire has proven to be successful in dramatically reducing violence.

The reduced violence in Darfur and comparatively secure ceasefire may be due to the Darfur referendum which took place on 11 April. The referendum is the supposed conclusion of the Doha Peace Process which started in 2011; it concerned whether Darfur would remain five separate states or a single unified region, and resulted in 97% of voters voting in favour of the status quo (BBC News, 23 April 2016). The main rebel groups all boycotted the referendum on the basis that unrest in the region, combined the high population of internally-displaced persons (IDPs), meant that many people will not get to vote (Middle East Eye, 9 April 2016). Both the SLM-MM and Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) stressed the importance of returning Darfur’s 2.5 million IDPs back to their villages (ibid.). It may also be the case that the decrease in rebel activity since January, in spite of their opposition to the timing of the referendum, is due to an attempt by the rebels to minimise unrest in the hopes of creating a more permissive voting environment.

The landslide victory and the unresolved issue of IDP resettlement means that it is highly unlikely that the referendum marks an end to the conflict in Darfur.

This report was originally featured in the June ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.