Since 2013, riots and protests have been the dominant political expression recorded in African countries in the ACLED dataset. Populations took to the streets to express their grievances at a higher rate than more violent organised activity conducted by rebel groups or political militias. In 2016, the recent protests in the Oromia region of Ethiopia, pre-electoral uprisings in Kenya, violent protests in South Africa and demonstrations by political activists and youth in Harare, Zimbabwe demonstrate how protest varies over time and space.

Where protest occurs and its spatial characteristics tells us a great deal about the political organisation of the state in that area and precipitators of wider forms of violence. Protests do not occur within a vacuum; “one cannot understand social life without understanding the arrangements of particular social actors in particular social times and places … [N]o social fact makes any sense abstracted from its context in social (and often geographic) space and social time” (Abbott cited in Lancaster and Kamman, 2016). Therefore, the spatial clustering, diffusion or containment of protest over space informs us of the local political structures that enable different forms of contention to emerge. Geography reveals who is involved in street demonstrations, how they are organised, facilitated or repressed, who stands to benefit, and their potential to mount a sustained challenge to regimes or escalate into wider patterns of violence. As such, we need to look beyond the immediate characteristics of protests themselves to examine their geography.

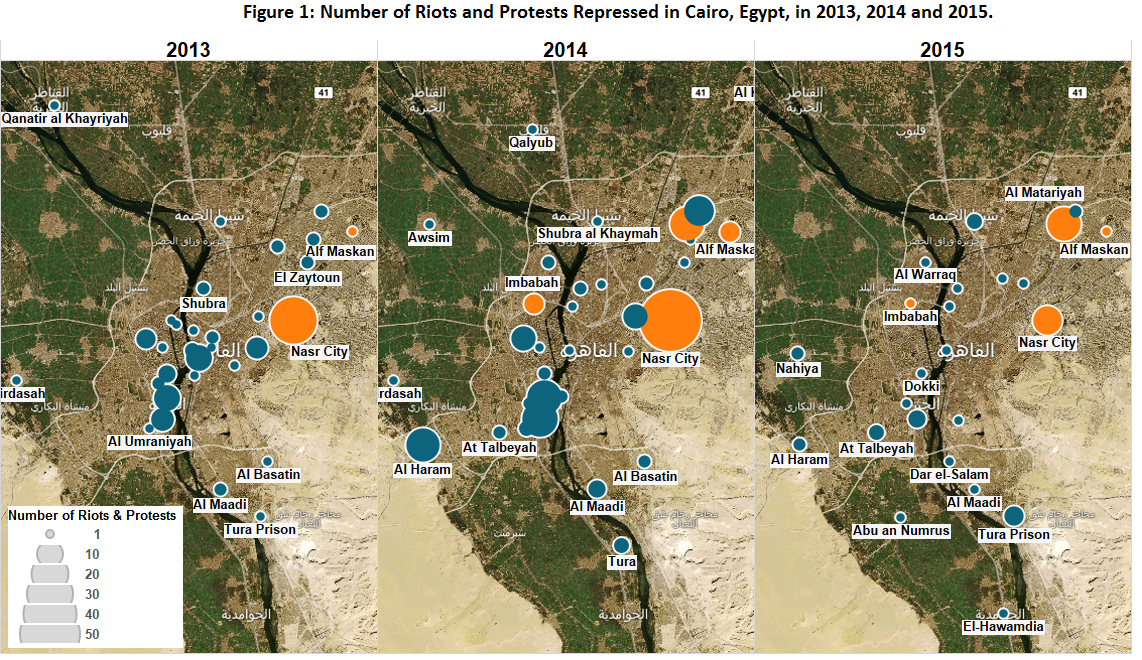

This report begins with a case study of the spatial patterns of protest and state repression in Cairo in 2013, 2014 and 2015. This reveals the prerogatives of the Egyptian regime and the ways in which they interpreted and responded to non-state threats. It illustrates how the structures of governance in African political systems (see Arriola, 2013) and the ability of protesters to organise condition where we see the emergence of protest. It then briefly analyses recent protests in Kenya and South Africa from a geographical perspective to show how protest patterns reflect local political contexts.

At the city-level, protesters often choose strategic locations for claims-making. This includes demonstrations outside institutions of state power, such as government buildings, political party offices or economic and financial areas to maximise their impact. But to emerge in the first place there must be a degree of organisation that enables this. The scale of organisation varies across contexts, from grass-roots networks outside of state control to integrated networks of local and national government such as in Zimbabwe. This conditions the logic and therefore the pattern of protest.

The case of Cairo demonstrates that the internal characteristics of the protest event alone, such as the number of participants or frequency of protest (see Biggs, 2016) cannot fully account for trends in protest dynamics. Figure 1 shows the distribution of protests that were repressed by Egyptian security forces in Cairo in 2013, 2014 and 2015. The map indicates a clear pattern of targeted state repression. The districts of Al Haram, Giza, Mohandiseen, Ain Shams, Zamalik and Zaytoun witnessed higher overall protests but were subject to none or much lower levels of state response. Instead, districts cited as Muslim Brotherhood ‘strongholds’ (Nasr City, Imbabah, Alf Maskan and Al-Matariyya) (Atlantic Council, 12 January 2015; BBC 5 September 2013; Elaph, 24 August 2011; Mada Masr, 25 January 2014) were consistently subject to heavy repression (highlighted in orange, see Figure 1). Furthermore, the level of indiscriminate state violence against unarmed civilians also concentrated in the same areas from 2013-2015. This pattern demonstrates the level of threat the regime perceived from the protests due to their capacity to organise relative to other weak political and civic parties. In 2011, an ‘unholy alliance’ was struck between the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) and the Muslim Brotherhood “in a bid to buy votes and provide Islamist parties a military supported upper hand in the upcoming parliamentary elections” (Huffington Post, 23 November 2011). However, once the SCAF had secured its position and the Brotherhood’s comparatively strong organisation led to a power base that threatened to undermine the interests of the military, state-led violence targeted those areas where grassroots networks had the potential to destabilise the regime. Here, local political contexts manifested into geography, resulting in the patterns of violent contention observed in Figure 1.

Despite calls for nationwide protests against the IEBC, recent electoral violence in Kenya, protests have predominantly concentrated in Kisumu. Whilst the Coalition for Reforms and Democracy (CORD) called for nationwide protests (Standard Media, 24 May 2016) so far they have only managed to take a foot hold in Nairobi, where they are mobilised and led by Raila Odinga and in the southwest Nyanza region, which enjoys strong opposition support. Similarly, protests occurred in Nairobi over the extrajudicial killing of a lawyer (Guardian, 4 July 2016), but in areas that have experienced similar grievances against police brutality, such as Mandera County where Kenya’s ethnic Somalis are reportedly subject to state violence (Pulitzer Centre, 8 January 2016) protests are largely absent. As Will Swanson notes “[it] seems #Kenya‘s protest movement is reserved for down country Kenyans, no protests for killings on the coast.” To explain the spatial distribution of protests in this context researchers must go beyond grievances to examine networks of power and the political organization of the state that facilitates or promotes collective violence.

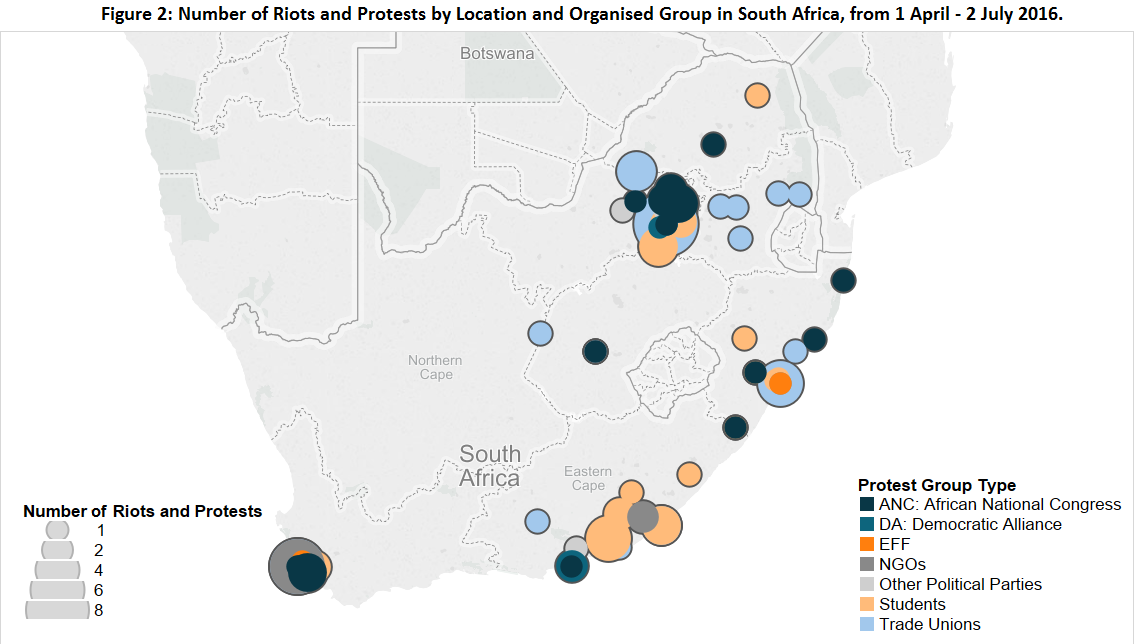

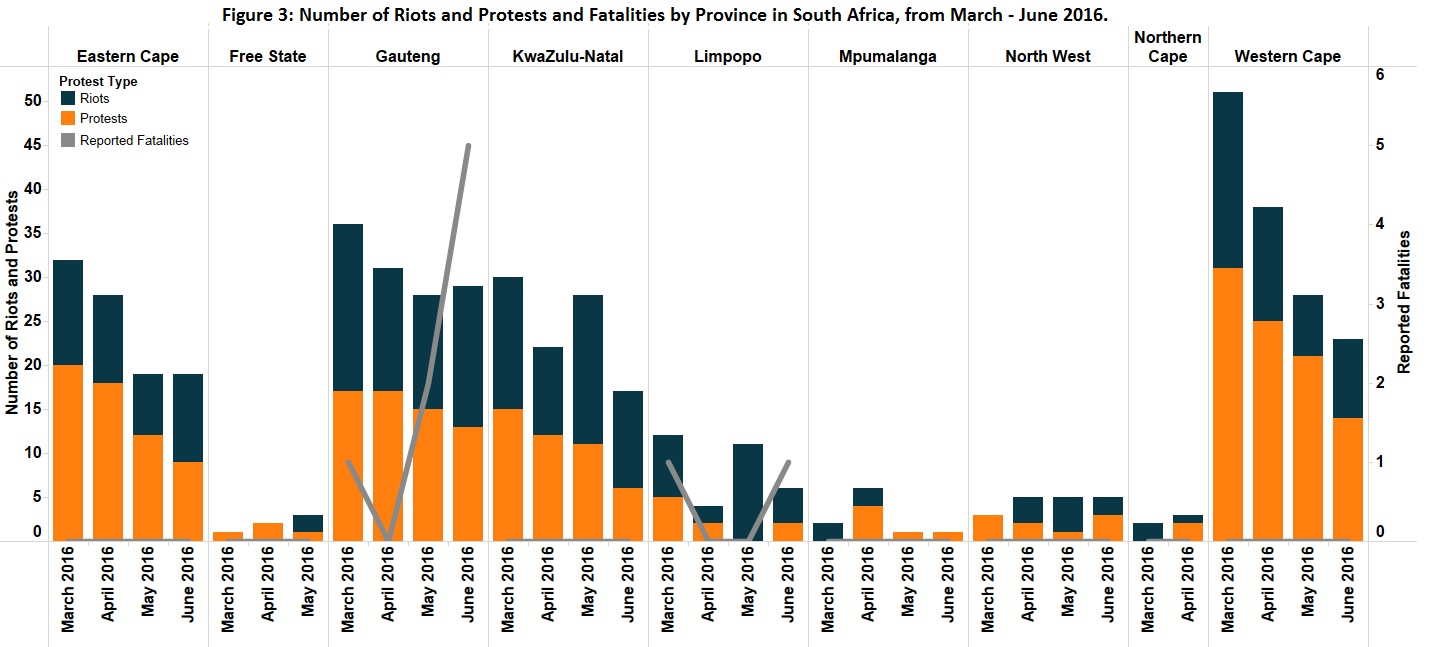

By contrast, the wave of violent protests in South Africa have been much more diffuse, with multiple protest movements co-occurring over mayoral candidates and electoral lists, student clashes on university campuses in Cape Town and Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and other worker-based protests (see Figure 2). Born out of intra-ANC competition, violent protests have fuelled violence for local representation and redistribution. Concentrated in large urban areas, the successful political candidate would gain access to a huge body of states funds for redistribution. This contrasts with the voter registration protests in March and April 2016, which predominantly took place in ANC-dominated rural localities with populations under 100,000 who were dissatisfied with ruling party performance. Strikingly, these protests have remained localised, lacking coordination and leadership against a central regime or policy.

In both of these instances, the issue of space and the influence of political structures influences the form and location of protest (see Figure 3). As the political process develops, intra-ANC violence is predicted to turn into inter-party violence, concentrating in Gauteng (ISS, 1 July 2016). In theory the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) have an opportunity to capitalise on the protests that erupted in Pretoria, Durban and Port Elizabeth in late June 2016. Yet, should the protests continue to decrease support for the ANC (Bloomberg, 30 June 2016) without the need to bridge ties between other discrete movements, it is politically expedient for the EFF to stand on the side-lines. Therefore, these protests are unlikely to be channelled into a more coherent, organised and spatially concentrated movement if this trend continues.

This report was originally featured in the July ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.