Since the beginning of 2016, riots and protests in DR-Congo have generally fallen into two broad categories. First, protests against the presidential election delay scheduled to be held in late November 2016, a concern which was recently confirmed when the Independent National Electoral Commission (CENI) announced that the election will be pushed back to 2018 (Bloomberg, 29 September 2016). Second, protest events related to insecurity, with the most prevalent being those motivated by attacks on Beni territory by suspected ADF rebels but also occasionally prompted by violence in other areas of the country. While these two categories are not exhaustive, other protests in the country are largely sporadic and isolated.

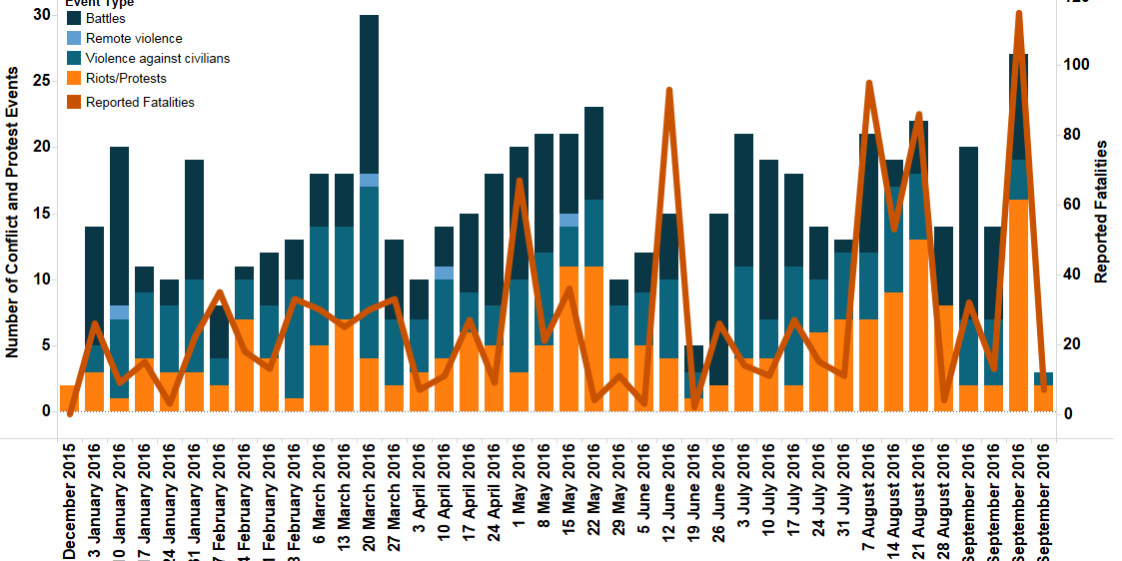

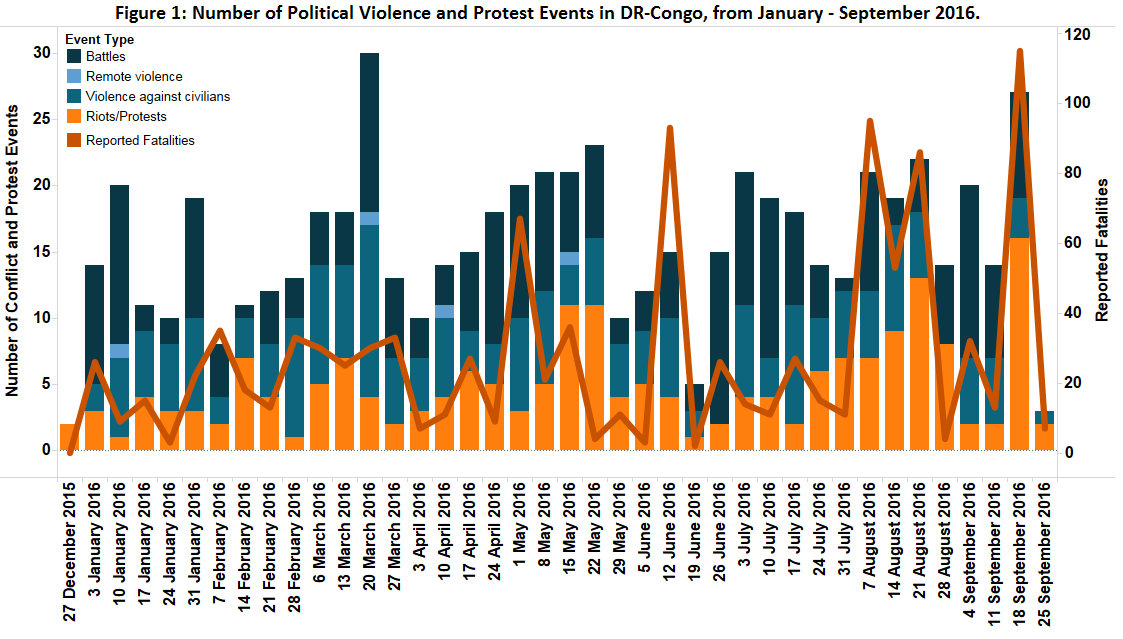

There have been several notable episodes of election-related riots and protests in 2016 (see Figure 1). The first included a 24-hour national strike called by the G7 opposition coalition to demand elections within the constitutionally mandated-deadline in February. Strikes in Kinshasa and some major cities in the east, including Bukavu, Uvira and Goma were well attended (Reuters, 16 February 2016). Following this, a day of demonstrations on 26 May 2016 saw protests against the constitutional court decision to allow Congolese President Joseph Kabila to stay in power beyond the end of his term in 2016 while elections were organized, resulting in at least one protester killed in Goma (Al Jazeera, 26 May 2016). During the 26 May events, protests in Kinshasa also resulted in a number of injuries, although similar events remained peaceful in the cities of Kisangani, Moba, Kalemie, Bukavu and Beni. Other significant election protests in 2016 occurred on 19 January (Congo Research Group, 20 January 2016) and 7 July (National Post, 31 July 2016), both of which drew thousands of demonstrators to demand presidential elections be held in 2016 and were largely peaceful. The G7 coalition organised the majority of election-related demonstrations and later by the Rally of the Congolese Opposition (OCR), a coalition of opposition parties that came together to more effectively contest the presidential election.

By far the most significant bout of election-related mass demonstrations in 2016 were those witnessed in late September. On 19 September, the OCR rallied demonstrators in a number of cities across the DR-Congo demanding that elections be held in 2016. While a number of demonstrations occurred without reports of violence, Congolese security forces dispersed those in Beni and Matadi with a number of injuries reported (Radio Okapi, 23 September 2016). By comparison, Kinshasa saw an unprecedented number of protester and police fatalities during two days of violent protests. At least 32 people were reported killed in the violence, including at least six police officers (Washington Post, 21 September 2016). Assailants burned a number of opposition HQs, including the UDPS, the party representing the leading opposition presidential candidate Étienne Tshisekedi, as well as those of the ECIDE, FONUS, and MLP political parties (Al Jazeera, 21 September 2016). One of the political parties of the ruling coalition, the RCD, also allegedly had its HQ burnt by opposition protesters during the events of 19-20 September (Radio Okapi, 20 September 2016).

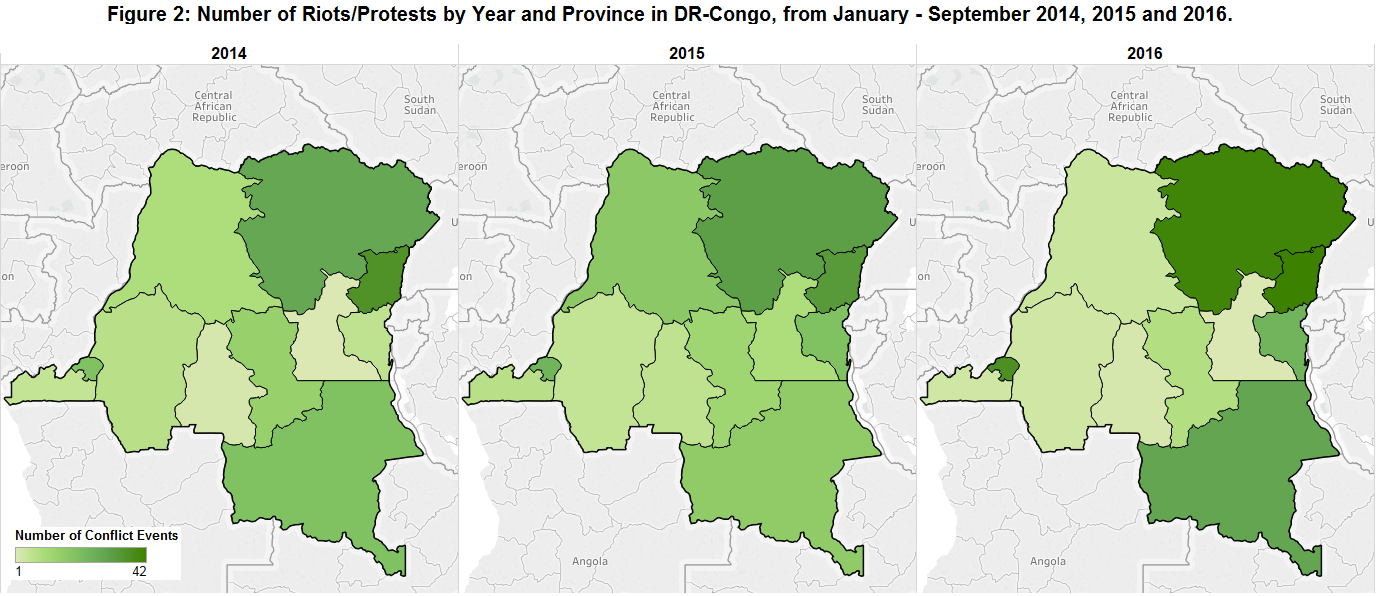

The DR-Congo regularly witnesses insecurity-related protests, particularly in response to rebel attacks in the eastern region of North Kivu (see Figure 2). The city of Beni is a notable focal point for demonstrations against the activities of the ADF which has been a regular perpetrator of mass killings of civilians over the past few years in Beni territory. In 2016, Beni territory alone has been the site of three major protest events related to insecurity. The first of these involved a coordinated 72-hour “dead city” protest strike in May against insecurity in North Kivu. These protests shut down Beni, Butembo, Eringeti, Lubero, Mbau and Oicha (Radio Okapi, 18 May 2016) following the killing of at least 30 civilians by suspected ADF rebels in separate attacks in the Eringeti area earlier in the month (Reliefweb, 11 May 2016). This bout of protests was followed by a major protest in Beni in August catalyzed by a suspected ADF attack on the Rwangoma suburb of the city that resulted in more than 40 civilian casualties (Al Jazeera, 14 August 2016). The demonstrations resulted in serious clashes between protesters and police which left at least one dead on either side (Reuters, 17 August 2016), while some incidents of vigilante and/or mob killings of suspected ADF members were also reported (Reliefweb, 24 August 2016). Most recently, another “dead city” protest strike in Beni on 23 September took place after suspected ADF rebels killed seven civilians in the Kasinga area of Rwenzori in Beni territory.

Although election-related and security-related riots and protest are the most notable in DR-Congo due to their associated risk of violence, a number of protest events motivated by socio-economic issues and local concerns transcend particular national situations. Many of the protests seen in DR-Congo involve concerns over pay, working conditions, or living conditions. However, these types of events are often entirely non-violent, usually peacefully dispersing without police intervention.

In summary, riots and protests surrounding both the issues of the election and insecurity have been gaining momentum over the course of the year as measured by the size of the protests and intensity of the violence involved. Growing frustrations by segments of the population in the capital, Kinshasa and in North Kivu over the government’s unwillingness to adhere to the election schedule and perceived inability to provide security clearly translate into collective action. Protests have similarly kept apace in Katanga province, where opposition leader Moise Katumbi holds a strong support base to rally demonstrators. Less clear is the increasing trend of protest clustering in South Kivu, particularly Bukavu since 2014. Looking to where protests were violently repressed and which cities authorised protests (Jewish World Watch, 26 May 2016) should reveal more insight into the location, form and intensity of growing popular frustration in the future.

This report was originally featured in the October ACLED Africa Conflict Trends Report.