Somalia continues to be the most conflict-affected country across Africa. It has experienced almost twice as many violent events in the past two years as the second most affected state of Nigeria; however, Nigerian fatalities for the same period are more than double Somalia’s total. Since early 2015, three main patterns have emerged: the war’s threat to civilians varies significantly across the state; second, while Al Shabaab and the state are engaged in intense and frequent battles, their combined conflict amounts to just over half of all violence. Relatedly, there are several dozen intense, ongoing and fatal competitions for local and regional power playing out in Somalia. Finally, in October 2015, ISIS and Al Shabaab supposedly joined forces to expand the agenda of both; a recent video from Puntland suggests this is the area chosen as a testing ground. There remains little activity recorded by the Islamic State in Somalia, but distinct increases in Al Shabaab’s activity in new northern spaces. The remainder of this piece will concentrate on the first two patterns.

Variance in Violence Against Civilians

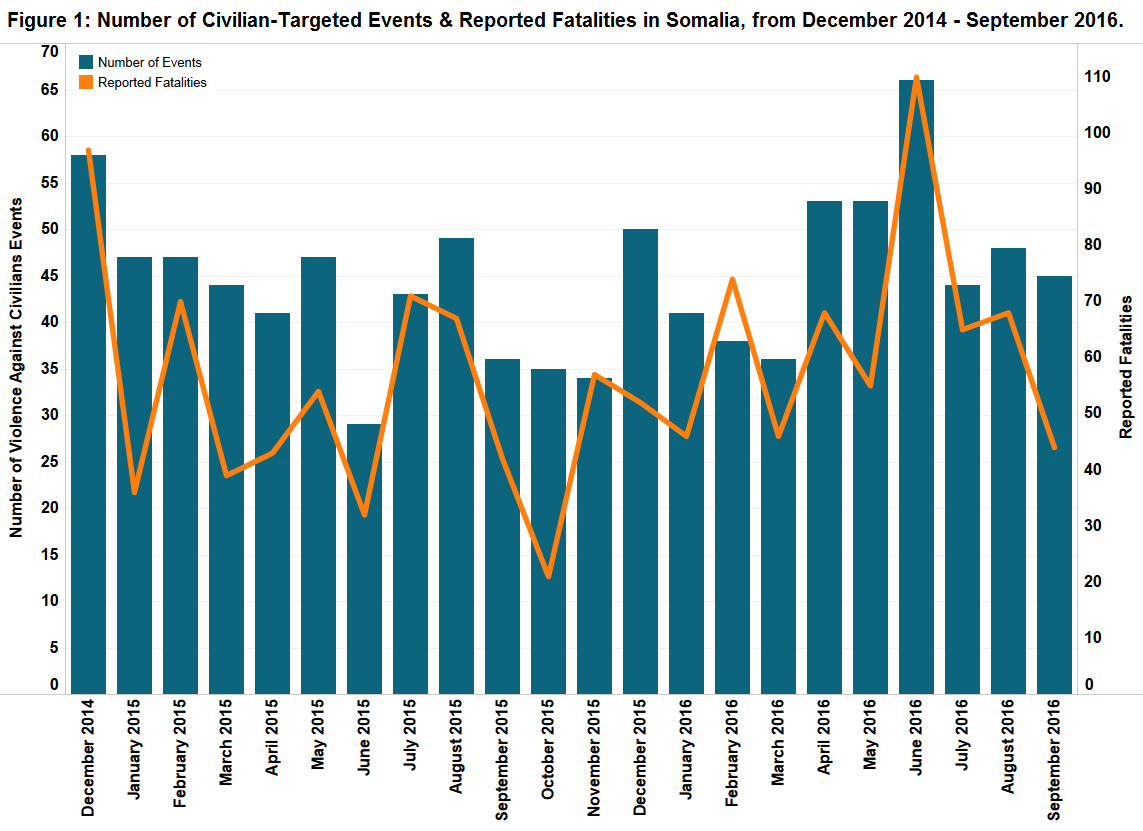

Between January 2015 and October 2016, anti-civilian violence in Somalia made up approximately 23% of all recorded violent events; and 14% of associated reported fatalities. As a proportional share of overall violence, anti-civilian violence events have shown a steady trend since the beginning of 2015, with June 2016 being the most violent month for civilians (see Figure 1). Approximately 13% of anti-civilian violence events, and 13% of associated reported fatalities, involved remote violence technologies.

Since January 2015, political militias (including unidentified armed groups) have been responsible for the largest share of anti-civilian violence events (approximately 44%), followed by rebel forces (Al Shabaab, 26%), and communal militias (14%). In terms of associated reported fatalities, Al Shabaab has been responsible for the largest share (37%).

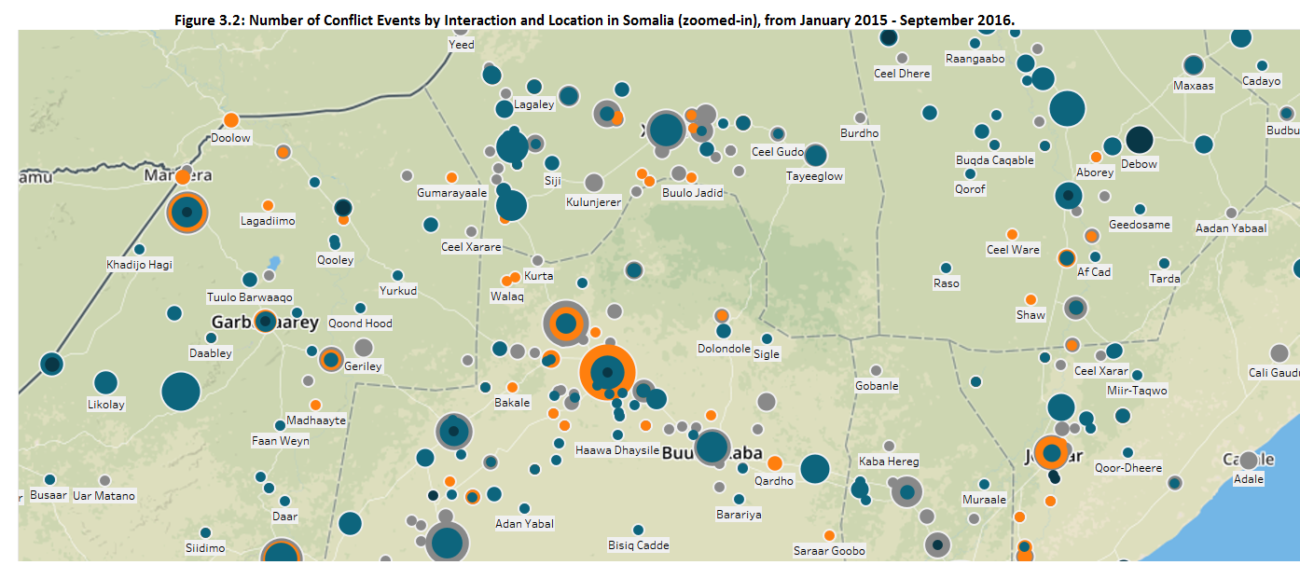

But violence against civilians in Somalia varies considerably: regions including Mudug, Banaadir, Bari and Middle Juba all have considerably higher than average rates of civilian targeting by administrative district (+20%,+5%, +15%, +12%, respectively), while surrounding regions, and those bordering both Kenya and Ethiopia have lower reported rates.

Who Fights?

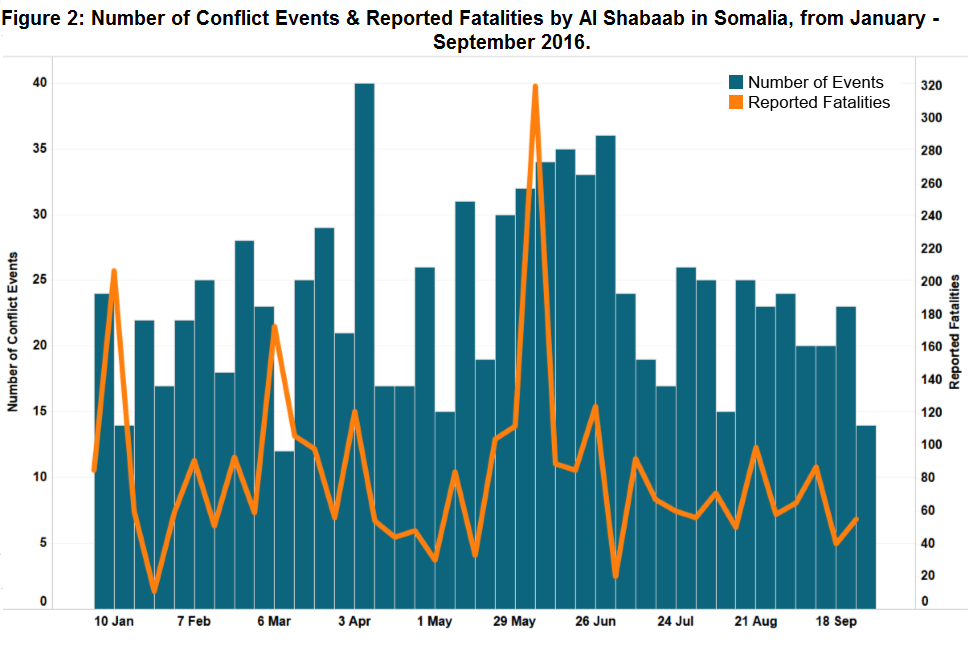

Somalia’s conflict continues to be dictated by Al Shabaab who are engaged in 30% of all violent occurrences from 2015 to October 2016 (see Figure 2). In contrast, state forces are engaged in two thirds of the activity of Al Shabaab. Al Shabaab has considerably strengthened over the past two years, dominating new spaces in Mudug and beyond as they seek to expand their base and accommodate multiple local affiliates and their respective contests. In contrast, state forces have poor permanent presence across much of the state, and have reduced capacity in the past two years, gauged by the increase in direct attacks by non-state agents on state bodies and institutions (e.g. such as the increase of attacks in Galgadud).

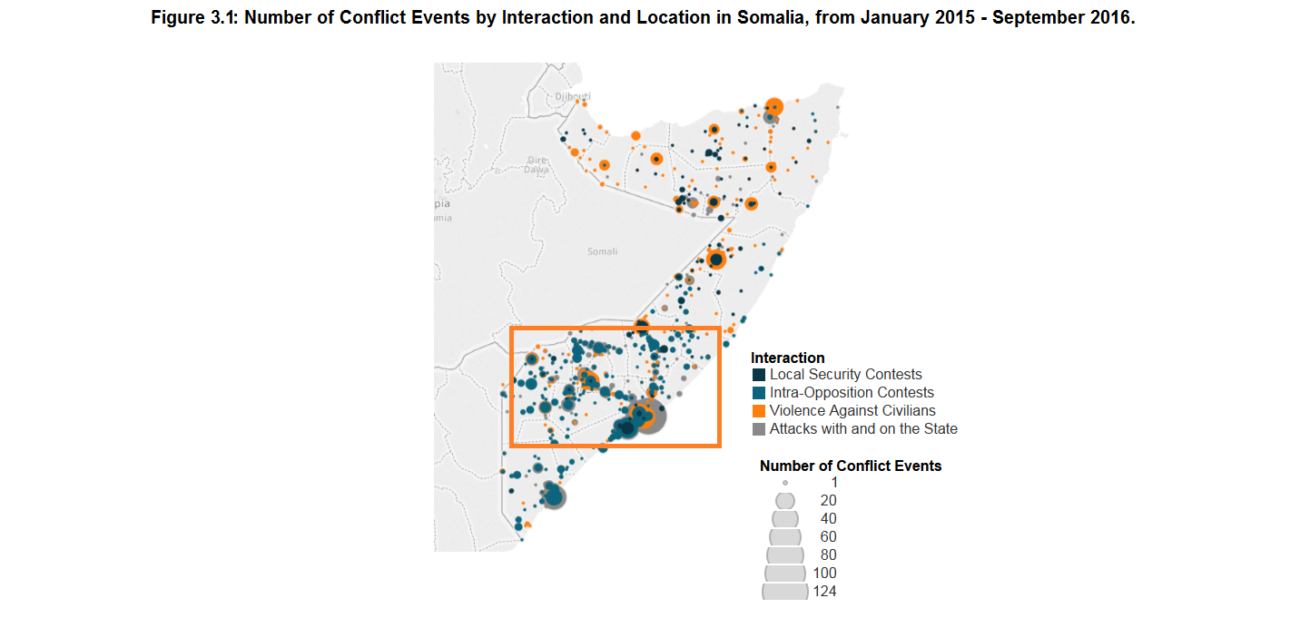

But the activity of Al Shabaab and state military forces does not explain the remaining fifty per cent of conflict that occurs throughout the state. Conflict in Somalia can be best characterized as occurring over four distinct scales and environments where the focus is on who is fighting with whom, and the risks to both state and civilians as a result. To that end, the four categories of (1) the attacks from and on the state, (2) violence against civilians, (3) intra-opposition contests and (4) local security contests. The first type of violence in Somalia involves all branches of the state in their contests with other opposition groups and with each other- that violence is 44% of all occurrences since January 2015. It is primarily concentrated in attempts to secure Banaadir and its surroundings, but as of April 2016, decreased substantially. This may be one reason that the government has determined that elections must be postponed until November of this year. In a recent statement, it blamed Al Shabaab. However, previous attempts to deal with elections in a time of insecurity have reinforced the power of local elites who select the national government, rather than the citizens of the state. There is some reason to believe that the competition between local and regional power holders is the reason for a high, consistent and varied rate of ‘intra-opposition’ fighting, involving militias belonging to politicians, governors, local power holders, large clan leaders and others. This violence alone accounts for 24% of all recent acts.

Smaller clans and their internal disputes with neighbours and clans of similar size are widespread, but account for a small amount of violence (approximately 5%). Finally, threats to civilians are separate attacks that all of the above engage in. This violence is one third of all reported events, and closely follows the spatial and temporal dynamics of violence towards and with the state. In short, in areas where groups are fighting the state, they (and the state) are also engaged in civilian attacks. Contests that do not involve the state may result in high insecurity for civilians, but at a lesser rate than regime competition attacks.

As noted in Figure 3, the majority of contests between armed actors occurs on main roads across Somalia – this indicates high and ongoing competition for all spaces as state forces do not adequately control and hold main areas.

This report was originally featured in the October ACLED Africa Conflict Trends Report.

Authors: Professor Clionadh Raleigh and Dr Roudabeh Kishi