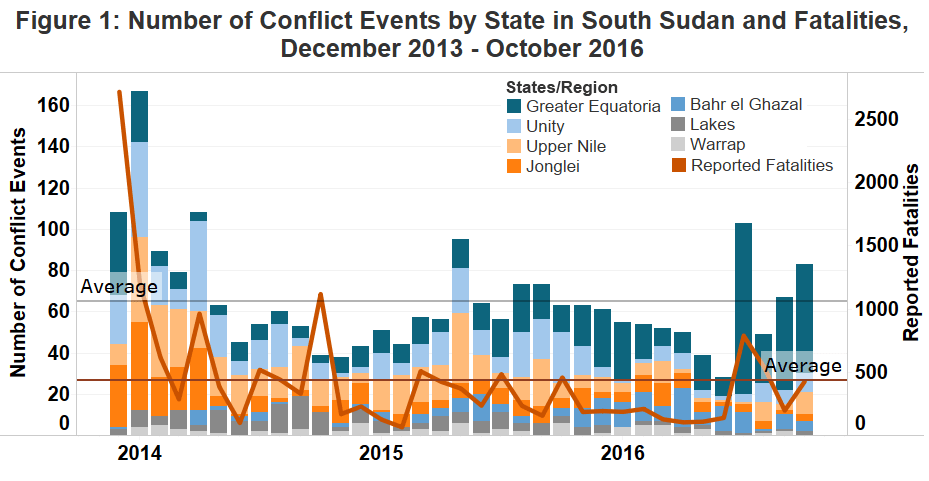

Political violence in South Sudan continued to increase through October, reaching its highest point since the battles in July when violence re-erupted in the capital between the government and the rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Army – In Opposition (SPLA-IO). Since July, the spread of conflict remained localised to the Greater Equatoria region (see Figure 1).

This marks a contrast to the outbreak of the civil war in Juba in late 2013, where conflict quickly spread to states where SPLA-IO leader and former vice president Riek Machar had a following (in Unity), where previous instances of rebellion had occurred (in Jonglei), and to the key oil region of Upper Nile.

There are three potential reasons for this trend. Firstly, the SPLA-IO has gained grounds in Greater Equatoria over the past few months and remains committed to overthrow the government. Secondly, there has been a rise in political militias battling government forces and targeting civilians in the region. Lastly, government forces have engaged in violent counter-insurgency tactics and targeted perceived supporters of the opposition within Equatoria.

SPLA-IO’s rising foothold in Greater Equatoria

The geography of conflict in South Sudan started to shift west by December 2015 (see ACLED, June 2016), primarily driven by expanded fighting between government and SPLA-IO allied rebels in Western Equatoria. Machar used ambiguity in the August 2015 peace deal to ask for 19 cantonment sites outside of Greater Upper Nile, including 11 in Greater Equatoria, which would merge his forces with anti-government groups within Equatoria. President Kiir, under pressure from anti-peace elements on his side, rejected the notion that groups outside Greater Upper Nile were related to the conflict and continued to prevent rebels from gathering at the designated cantonment sites (Small Arms Survey, July 2016; Radio Tamazuj, 2016). By late 2015, anti-government grievances and anti-Dinka sentiment had risen among SPLA-IO-allied factions in Western Equatoria state, including factions of the Arrow Boys militia. This prompted the government to launch a counter-insurgency campaign, during which abuses were committed by both sides (HRW, 6 March 2016).

During the July violence in Juba, Machar’s ability to bring in support from aligned rebel groups outside the capital proved limited, primarily due to the groups’ limited resources (RFI, 18 August 2016; Small Arms Survey, July 2016). The clashes drove Machar’s outgunned forces out of Juba and into the Greater Equatoria region, where they have remained mobilized and are engaged in active recruitment (ICG, 17 August 2016). From South Africa, where he fled for protection after the clashes, Machar declared that the peace deal had collapsed and called for the reorganization of his forces to “wage a popular armed resistance against the authoritarian and fascist regime of President Salva Kiir” (RFI, 25 August 2016). His calls for continued resistance resonated in Greater Equatoria as his rebellion was joined by a number of soldiers and civil servants who defected from the government, as well as by new groups such as Lam Akol’s New Democratic Movement (NDM) and the South Sudan Democratic Front (SSDF) (Sudan Tribune, 25 September 2016; Sudan Tribune, 31 October 2016).

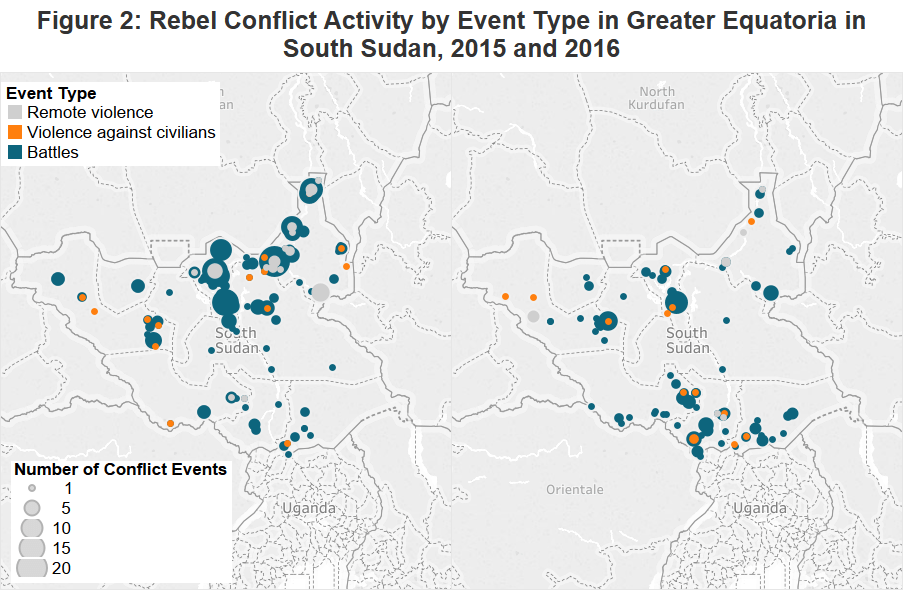

Directly after the clashes in the capital, opposition and government forces fought in the forests to the south and west of Juba (Sudan Tribune, 2 August 2016). Until early August, their battles split along two suspected escape routes used by Machar across Central and Eastern Equatoria. Towards the DRC, major battles took place in Lainya and Yei counties, while on the way to Uganda, fighting was reported in Torit and Magwi (Sudan Tribune, 10 August 2016). Throughout September and October, battles have continued in these counties and were particularly sustained in Yei. But violence has also expanded to others areas such as Morobo county in Central Equatoria, where SPLA-IO briefly captured the main town on 30 October, to Chukudum in Budi county of Eastern Equatoria, and to Mundri counties in Western Equatoria where gains were also made by the opposition in Kediba (see Figure 2; Radio Tamazuj, 1 October 2016; Radio Tamazuj, 20 October 2016; Sudan Tribune, 10 October 2016).

Suspected SPLA-IO rebels have also carried out several attacks on commercial vehicles travelling along the main Juba-Nimule highway linking South Sudan and Uganda, leaving dozens of people killed, injured or abducted, including foreigners, and affecting trade between the two countries (Daily Monitor, 5 September 2016; Radio Tamazuj, 24 September 2016). Nevertheless, the SPLA-IO remains responsible for comparatively few attacks against civilians.

Increasing attacks by unidentified groups

Since the Juba clashes, there has been a surge in violent activity by unidentified armed groups (UAGs) in Greater Equatoria, with UAGs accounting for 28.6% and 41.25% of violent events in September and October respectively.

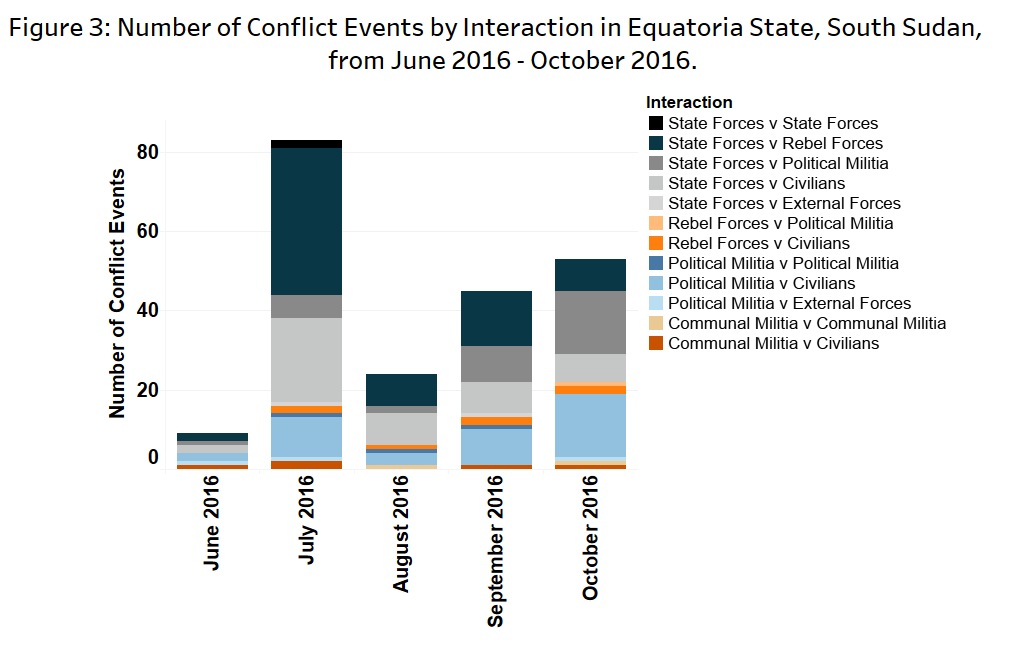

The Juba clashes left Machar relatively weakened. In addition to being ousted from the capital, Kiir’s nomination of former SPLA-IO chief negotiator Taban Deng Gai as the new Vice-President after the clashes further side-lined Machar on the political stage and divided his fighters (RFI, 18 August 2016; IRIN, 12 October 2016). While some have continued to fight with the SPLA-IO, it is likely that a number of gunmen within Greater Equatoria have split to operate with relative autonomy and no longer fight under the SPLA-IO banner. The lack of a figurehead to force a consensus may explain the high incidence of battles between government forces and UAGs in Greater Equatoria, and the high incidence of UAGs and political militias targeting civilians (see Figure 3).

Additionally, the heavy-handed government response to rebellion in Greater Equatoria is likely to have fuelled renewed ethnic hatred and caused new guerrillas in the region (Gurtong, 1 November 2016). Rising ethnic rhetoric, hate speech and incitement to violence have recently been reported in the region and condemned by international observers, especially following a spate of fatal attacks targeting ethnic Dinkas by unidentified groups along trading routes (UNMISS, 11 October 2016). On 8 October militiamen opened fire on four lorries transporting about 200 passengers on the Juba-Yei road, leaving at least 30 people killed and 21 injured, mainly ethnic Dinkas (Radio Tamazuj, 11 October 2016). Other notable instances of violence against civilians by unidentified groups have included waves of night-time killings in Yei county at the end of August (Radio Tamazuj, 29 August 2016) and civilian killings in Wonduruba area of Juba targeting ethnic Dinkas (Sudan Tribune, 20 September 2016). Aid workers have also been specifically targeted throughout the three states, recently costing the life of a ZOA aid worker in Torit (OCHA, 20 October 2016). Political militias have also clashed with government forces on various occasions between July and October, most notably in Chukudum in Budi county of Eastern Equatoria early October, where they captured several parts of the town (Radio Tamazuj, 13 October 2016).

Rising VAC by government forces

The government’s response to rising anti-state violence in Greater Equatoria has been increasingly heavy-handed and directed at civilians perceived to be supporting the opposition (see Figure 3).

Many villages along Machar’s axis of retreat were attacked by government forces in July and early August, often in the aftermath of battles with SPLA-IO rebels (Gurtong, 1 November 2016). In mid-August, following battles with rebels, government forces reportedly killed, arrested and assaulted civilians in Wonduruba and in Lainya county (Sudan Tribune, 29 August 2016). After fighting in September in Yei, government forces again attacked civilians and looted property in villages in Yei county and the Lasu refugee camp, forcing thousands of people to flee to Yei town (UNHCR, 30 September 2016). In the most recent attack, government forces killed people and looted property in Mundri during fighting with SPLA-IO on 17-18 October (Sudan Tribune, 18 October 2016).

Dozens of cases of sexual violence against displaced women have been attributed to government soldiers, including assaults near UN protection sites in the capital, as well as incidents of violence against aid workers themselves (UN, 1 November 2016; Beaubien, 23 August 2016). This increasing violence against civilians and external bodies has occurred within the context of an increasingly hostile attitude by Kiir’s government to internal and external challenges (Sudan Tribune, 9 September 2016; Sudan Tribune, 8 September 2016).