Over the course of 2016, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DR-Congo) saw a rise in intensity of political violence, and the emergence of new trends. First, violence involving the ADF, FDLR and Mayi Mayi militias clustered in the Kivus and Orientale province and ethnic conflict between Bantus and Batwas, as well as Hutus and Nandes, continued from previous years. Second, politically motivated riots and protests resulted in almost twice as many fatalities in 2016 (101) as 2015 (52). Finally, the rise of the Kamwina Nsapu militia in the Kasaï-Central represents a concerning new dynamic.

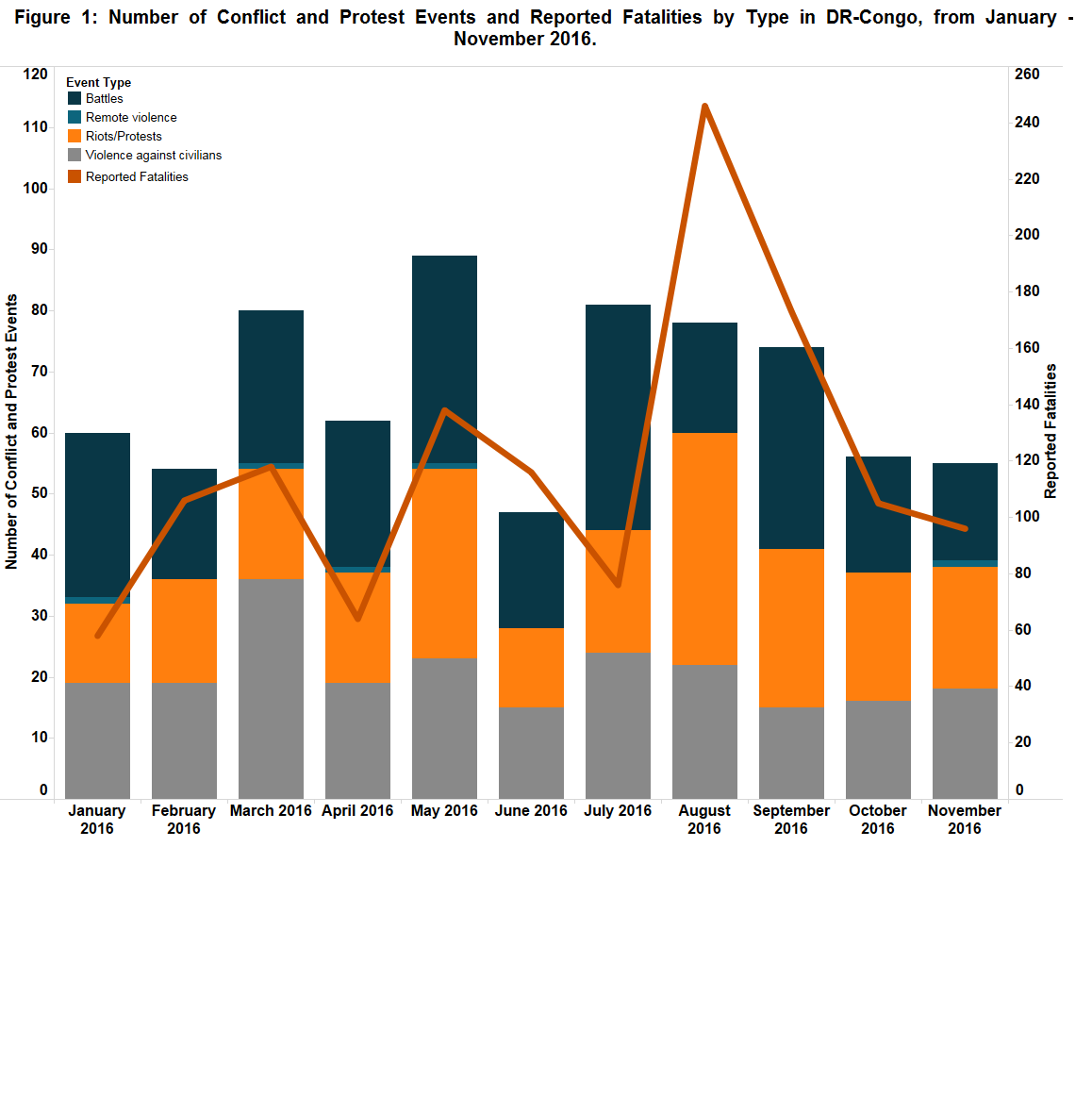

August was the most violent month in terms of fatalities, with 246 fatalities recorded, whilst May saw the highest number of discrete political events with 107 recorded (see Figure 1). The high fatalities in August are primarily attributed to an ongoing offensive against the ADF, with events involving the group responsible for more than half of all fatalities that month. Riots and protests over expected election delays and insecurity in the East, alongside military offensives against Mayi Mayi militias and clashes with the ADF and FDLR account for the significant number of events in May. August also marked the beginning of the government’s conflict with the Kamwina Nsapu militia.

In terms of actors, excluding non-violent events and riots and protests, the groups most represented in the data outside of government forces, unidentified actors, and civilians were Mayi Mayi militias (as an aggregated group), followed by the ADF, ethnic militias (as an aggregated group), and the FDLR. While this shows that the FDLR and ADF remain highly active in the country despite repeated offensives against them, the multitude of Mayi Mayi militias also remain an important destabilising force. The difficulty in dealing with these groups was evident during 2016 as Congolese forces pushed individual militias out of villages before later moving on, at which time the militias would re-occupy the territory they had lost, sometimes evicting police which had been deployed to the area, and continue to prey on the civilian populations. This lack of capacity to hold captured territory is one of the main reasons DR-Congo’s dozens of active Mayi Mayi militias remain such an entrenched part of the country’s conflict landscape.

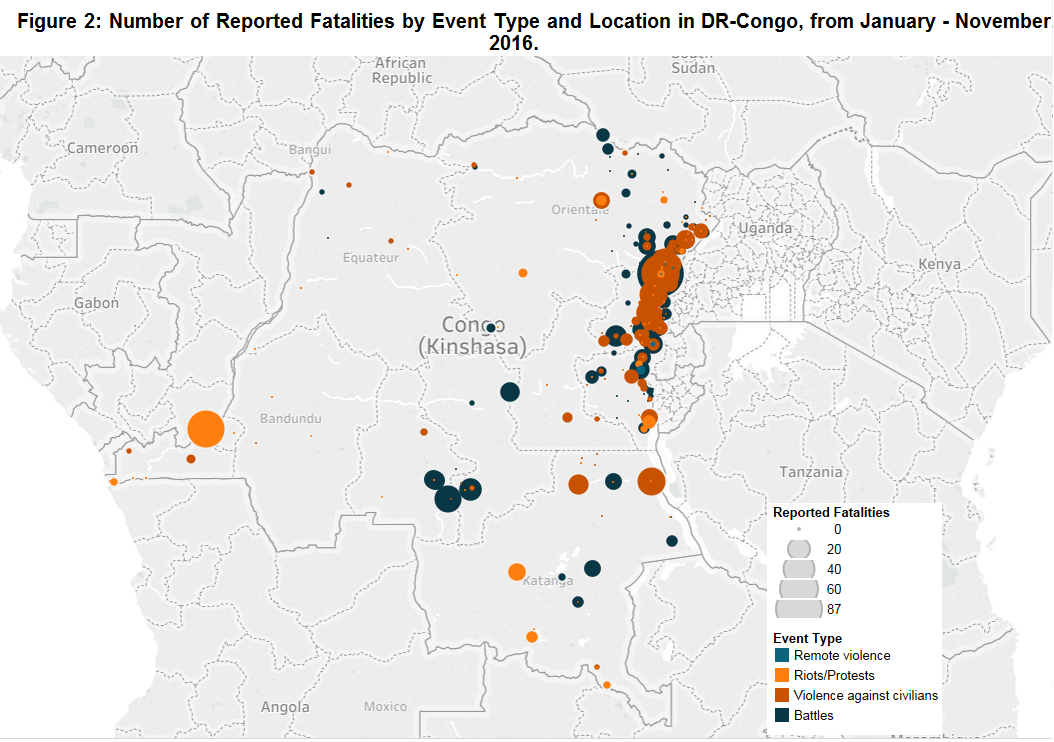

The bouts of ethnic violence witnessed in 2016, in particular between Bantu and Batwas (often referred to as pygmies by the media) in Katanga province and between Hutu and Nande, primarily in the Lubero area of South Kivu (see Figure 2), also represented a notable trend. This is because these types of conflict tend to escalate rapidly through cycles of reprisals which threaten to quickly spiral out of control. Reprisal in 2016 often targeted civilians, either through attacks on villages or assassinations of group leaders, and arguably strayed into active ethnic cleansing as hundreds or thousands were displaced following the reprisals. However, in the past both governmental and civil society groups have attempted to intervene rapidly in these conflicts, aware that this potential for quick escalation exists, as they did in 2015 in relation to the Bantu-Batwa conflict in the Manono area of Katanga province (UNICEF, 31 May 2016).

As of the end of November, both the Bantus/Batwas and Hutu/Nande ethnic dyads are engaged in another round of reprisal-based violence which is currently in the process of escalating. Recent notable examples of violence of this type includes an attack by Batwa killed 30 Bantu in the Muswaki area on 20 November (World Bulletin, 25 November 2016) and an attack by a Nande ethnic militia, the Mazembe Mayi Mayi group, on an IDP camp in Luhanga which killed as many as 34 people, primarily ethnic Hutus, on 27 November (World Bulletin, 27 November 2016).

In terms of riots and protests, two main trends can be identified in 2016 for the DR-Congo: escalating election-related protests and concerns over insecurity in the East (ACLED Crisis Blog, 7 October 2016). An unprecedented number of fatalities were recorded in riots and protests in 2016, more than any year since ACLED started recording, with the majority of these concentrated in Kinshasa between 19-20 January. These events resulted in as many as forty-nine civilians and six police officers killed, numerous incidents of vandalism and looting, and many political HQs of both the opposition and ruling coalitions burned down (see Figure 2). Other notable riot and protest events resulting in fatalities in 2016 included clashes between police and demobilized fighters (14 fatalities in 3 events) and police engagements with protesters denouncing insecurity, primarily taking place in cities in the Eastern DR-Congo (6 fatalities in 3 events).

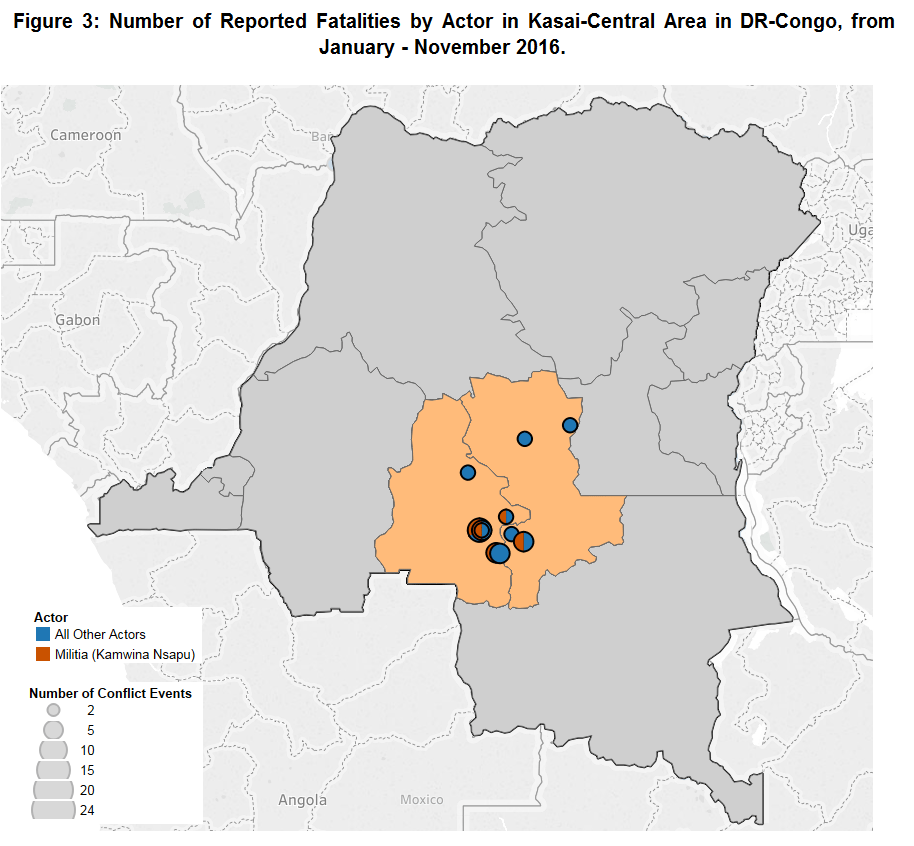

A unique trend in the data in 2016 for DR-Congo was the rise of the Kamwina Nsapu (KN) militia, which was formed in August 2016 and based in the province of Kasaï-Central (formed in 2015 from parts of Kasaï-Oriental and Kasaï-Occidental; see Figure 3). The group has continued to engage in attacks since its formation, with its most recent activity involving clashes with security forces in Tshikapa (Radio Okapi, 4 December 2016). These clashes came shortly after the beheading of two police officers accused of rape by suspected KN militiamen in Kabeya-Lumbu, and a subsequent ambush of government reinforcements sent to the area that resulted in at least 10 security personnel killed in an ambush around 30 November (Gulf News, 3 December 2016).

The KN militia was formed by Kamwina Nsapu, a traditional chief opposed to the central government (IBT, September 24, 2016) that announced his intention to “rid Kasai-Central of all law enforcement agents” whom he claimed were engaged in harassment of the population. The group’s activities seem to support this objective as KN militiamen have solely been recorded as engaging in clashes against security forces, with no attacks specifically targeting civilians recorded by ACLED as of the end of November 2016 (although collateral fatalities among civilians have been recorded, as well as vandalism and looting of public buildings). The first recorded instance of KN militia activity involved clashes between KN militiamen and police in the Tshimbulu area, first on 8 August resulting in nine fatalities, and then again on 12 August, resulting in eleven police and eight militiamen killed including chief Kamwina Nsapu himself. Following these events, the provincial governor labelled the chief and his militia as “terrorists” (Radio Okapi, 13 August 2016). The next month, KN militiamen staged a major attack between 22-23 September on the provincial capital of Kananga, and specifically its airport, which left at least fourteen dead. The militiamen were allegedly seeking to avenge their dead leader (BBC News, 24 September 2016).

Further activity by the KN militiamen – involving the temporary, non-violent occupation of Dimbelenge in late September and clashes with security forces in the Kena Nkuna area in mid-October – was followed by a lull that was punctuated by the violence mentioned previously around the end of November. However, although these events have brought a new degree of instability to Kasaï-Central, which has not seen violence on this scale since the Second Congo War, it is not yet clear what lasting impact this militia will have. Notwithstanding, the average fatality count of the fourteen battles ACLED has recorded KN militiamen participating in is 6.5 for a total of 91 fatalities (this number represents casualties on both sides, as well as collateral deaths; see Figure 3). This relatively high average, with around 47 of those killed being militiamen and 35 security personnel, gives some idea of the threat-level posed by this militia. When combined with their willingness to attack a city as large as Kananga, they have the potential to cause serious danger to the stability of central DR-Congo.

Notwithstanding the trends examined above, the DR-Congo is projected to witness a drop in total annual fatalities in 2016 compared to 2015. However, based on the many and varied sources of instability within the DR-Congo, from ethnic conflicts and disputes with the central government to anger over elections and insecurity, the country remains in a vulnerable position. Should these distinct conflicts escalate, it would likely exacerbate the country’s conflict landscape and present a challenge to the country’s conflict management capacities. This is a very real concern considering that the UN peacekeeping mission MONUSCO already supports the Congolese military in its responses to the relatively traditional threats posed by eastern rebel groups such as the ADF and FDLR. Further deterioration of the security situation, as well as the escalation of potentially overlapping ethnic conflicts coupled with the new threat represented by the KN militia, would seriously challenge the capacity of the already overstretched Congolese forces to maintain the existing level of relative security.

On top of these largely disconnected dynamics there is also growing concern over the potential for renewed protests and possible escalating violence as Congolese President Joseph Kabila attempts to extend his term limit (The Guardian, 10 November 2016). This situation remains volatile as elections scheduled for November 2016 have been postponed until at least 2018 (Brookings, 22 November 2016) and it remains to be seen how the opposition will respond to this. Although currently unlikely, if armed resistance does result from President Kabila’s bid to extend his time in office as opposition leaders have warned (The Guardian, 10 November 2016), this would have considerable negative ramifications for stability and security throughout the country and would thus presents the biggest threat to the DR-Congo as the country looks towards 2017.