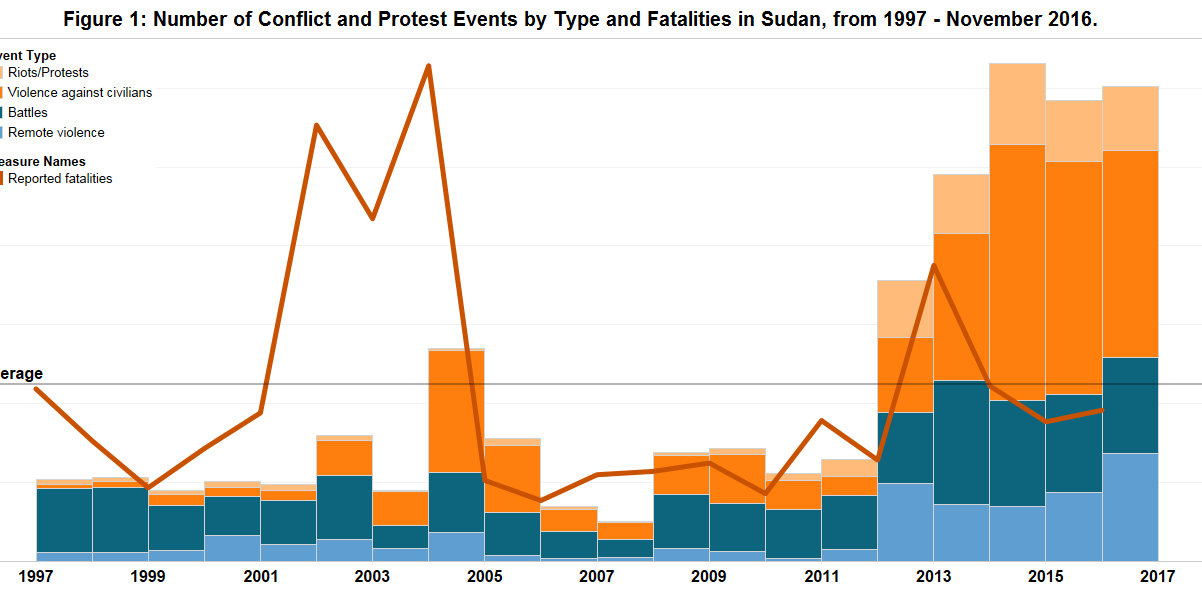

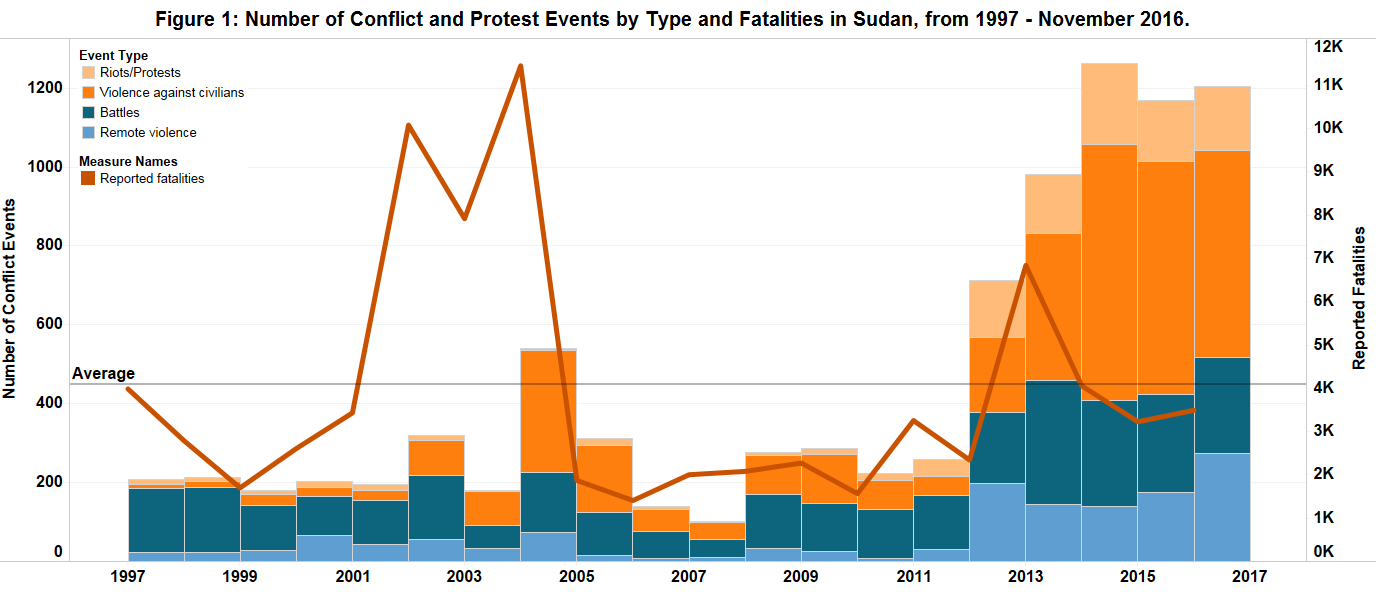

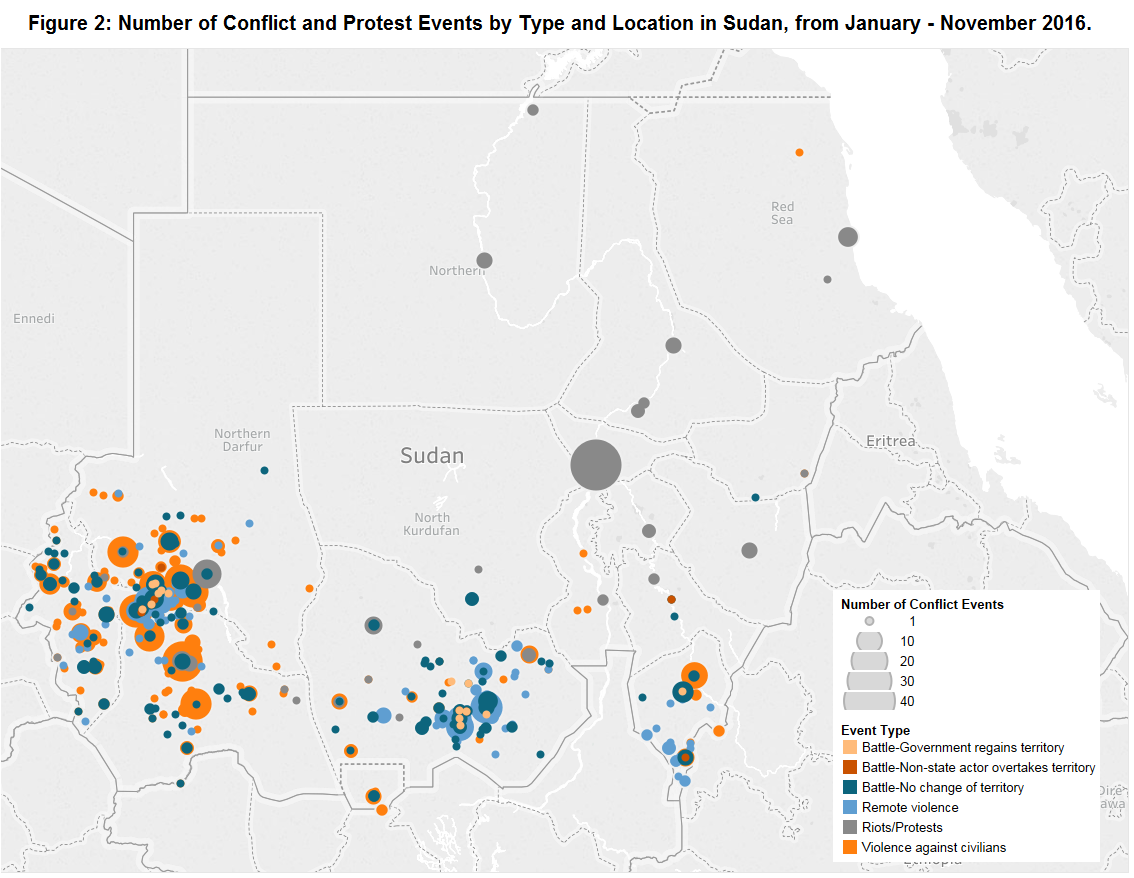

With political violence levels at their second highest point since 1997 as per the ACLED dataset, Sudan placed itself as the fourth most active conflict country in Africa in 2016. Despite a slight decrease in the level of reported battles and violence against civilians compared to 2013 and 2014 respectively, the country saw a significant rise in remote warfare (reaching its highest level since 1997 with 275 records) and maintained sustained levels of fatalities (nearly 3,490 as of early December) and repression of protest movements (see Figure 1). Darfur continued to capture most of Sudan’s political violence activity, with nearly 62% of events recorded in the state. However, political violence in Darfur has been declining since 2014, and gaining grounds eastwards in the states of Kordofan, Blue Nile and Khartoum (see Figure 2). This piece focuses on the main trends in government/opposition warfare in these states in 2016, as well as on the state response to the latest wave of protests in Khartoum.

Warfare

Conflict spiked in Sudan in the first half of the year, primarily driven by battles opposing government and rebel forces, which reached their highest levels since 1997. These were mainly opposing government and Sudan Liberation Movement/Army forces aligned with Abdul Wahud al-Nur (SLM/A-Nur) in Darfur’s Jebel Marra over January-February, but clashes also escalated between the government and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement North (SPLM-N) in South Kordofan and Blue Nile over March-May (ACLED, June 2016; Figure 2). Battles and remote violence reduced in the second part of the year, due to the onset of the rainy season when mobility is restricted, and preparations for the November renewed fighting season.

Several trends have emerged:

1) Remote violence, corresponding mainly to aerial attacks perpetrated by government forces against alleged rebel strongholds, escalated in all three states in the context of these clashes, and continued throughout the rainy season. Remote violence events in Darfur almost doubled from 87 to 149 events between 2015 and 2016. In South Kordofan, they concurrently rose from 66 in 2015 to 100 in 2016, reaching levels unseen since the end of 2012, when a similar government aerial campaign targeted the SPLM-N in the Nuba Mountains (HRW, 12 December 2012). The ability of the government to regain territory from rebels through these campaigns is unclear. However, their effects on civilian populations, through the alleged use of indiscriminate, unguided and chemical weapons and the damaging of plantations and harvests, have been largely denounced (Amnesty International, 29 September 2016; Amnesty International, 4 October 2016; HRW, 8 September 2016).

2) In South Kordofan, offensives targeted areas previously unaffected by conflict but on which many populations rely for food production (Karkaria, Al Azraq and Al Maradis for instance) (Amnesty International, 29 September 2016). Government forces set up bases in these areas and stayed throughout the rainy season, building up their capacity ahead of the resumption of conflict in November, but also preventing civilians from returning to their homes and farming their crops. This was perceived as a strategy designed to push civilians out of rebel-held areas (Nuba Reports, 29 November 2016; Nuba Reports, 9 August 2016).

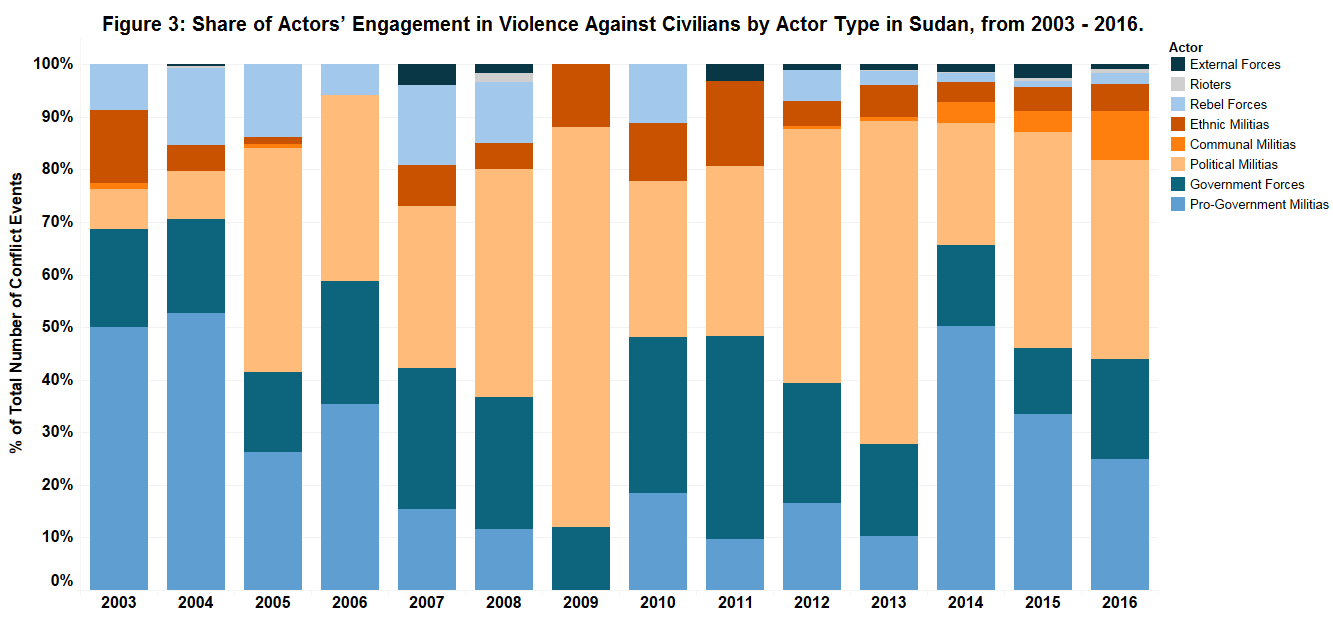

3) Pro-government militias, including the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and Janjaweed, supported ground offensives by government forces in the three states, a strategy so far predominant in Darfur (Amnesty International, 29 September 2016; HRW, 9 September 2015). RSF engaged in violence in Blue Nile for the first time since their creation in 2014 and have continued to operate in Kordofan, while Janjaweed activities in Darfur significantly increased from June onwards. Pro-government militias are mostly involved in violence against civilians and civilian property, including unlawful killings, abductions, rapes, lootings and burnings of properties (Amnesty International, 29 September 2016). Along with regular government forces, they are responsible for nearly half of the overall violence against civilians in the country (see Figure 3).

Clashes between government and opposition forces in 2016 have occurred against a backdrop of limited advances on the political stage; ceasefires proving difficult to hold as a result. SLM-AW has continued to reject direct negotiations with the government (UNSC, 28 October 2016), and while an opposition coalition signed the AU-brokered peace roadmap on 8 August, negotiations collapsed soon after over traditional points of discord such as humanitarian access to conflict-affected areas (Nuba Reports, 16 August 2016). SPLM-N suspended part of the negotiations with the government in the last part of the year, reacting to allegations of chemical weapons use and popular discontent over fuel subsidy cuts (Radio Dabanga, 23 October 2016; Radio Dabanga, 4 December 2016). With no agreement signed and no agreed date to renew negotiations, conflicts in Darfur, Kordofan and Blue Nile seem set to continue (Nuba reports, 16 August 2016).

Protests/Riots

Sudan was further destabilized in 2016 by sustained protests mainly in Khartoum (see Figure 1), and their violent repression by authorities. The latest and most significant wave of protests started in November, after authorities introduced austerity measures by cutting fuel subsidies, resulting in increased consumer goods’ prices. Economists and opposition leaders have criticized the abrupt timing of the measure and its un-alleviated impact on poorest populations – a concern sustained by president al-Bashir mentioning that the money saved would be used to support military efforts (Nuba Reports, 18 November 2016). Police dispersed a number of protests with tear gas, including by students, teachers, doctors and pharmacists, and detained dozens of protesters and critics among opposition parties. As of 29 November for instance, up to 27 members of the Sudanese Congress Party remained detained and incommunicado, and dozens of newspapers had been suspended over allegedly covering the protests (Radio Dabanga, 29 November 2016; Sudan Tribune, 2 December 2016). This pattern of economic protests and political arrests has been described as endangering the small gains made in 2016 by Khartoum in its negotiations with rebel forces and in bringing in the international community’s support for peace processes in the country (ICG, 30 November 2016).