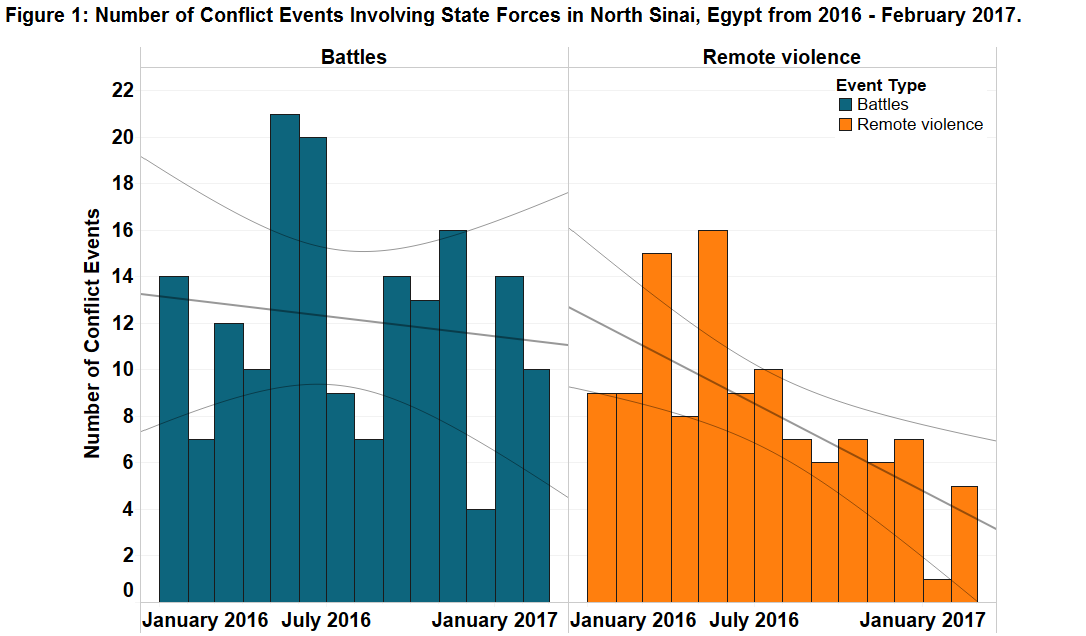

February saw a shift in the strategy of the Sinai Province militant group as attacks on Coptic Christian civilians and a resumption of aggression towards Israel replaced attacks against police officers and roadside bombings that had occurred since 2013. Seven Coptic Christian deaths at the hands of Islamist militants in one week led to civilians fleeing out of North Sinai to avoid further sectarian targeting. This escalation in North Sinai is occurring while military efforts to quash the Sinai Province group over the past few months is scaling down (see Figure 1).

Political analysts interpret attacks against Copts in two ways: as a means to weaken and attack the Egyptian regime, and a retaliatory measure against previous operations carried out in Al-Arish, Rafah and Sheikh Zuweyid by the army (Watani, 1 March 2017). But the Egyptian government’s role in the proliferation and maintenance of this violence is overlooked in these analyses. The continuation of a remote insurgency, in a historically marginalised and underrepresented region of the state, serves to justify repressive measures in more central regions of Egypt. This is in order to provide ballast against wider pockets of social unrest and contestation with the regime. In other words, nonviolent social and political mobilisation in areas with the capacity for political organisation continues to erode as the insurgency endures.

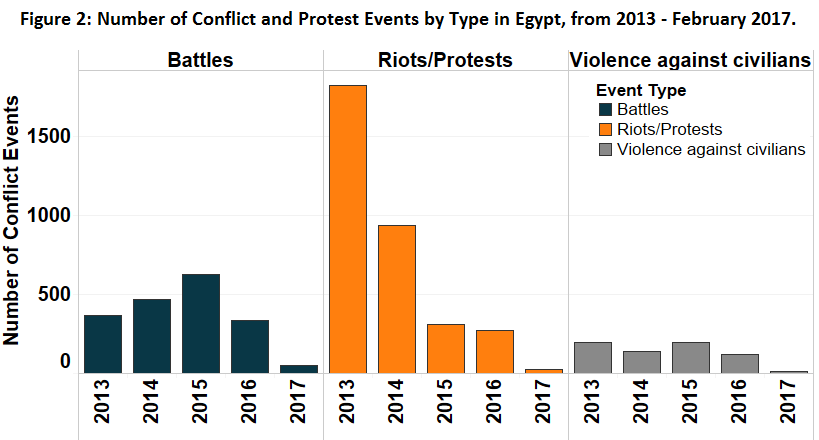

Popular protest has been declining in Egypt, although labour protest has continued (see Figure 2). The Egyptian army’s counter-insurgency operations have over the past two to three years consistently led to backlash (Fielding and Shortland, 2005), leading to the Sinai Province group to adjust its strategy, switching between targeting military and police outposts, to a re-engagement with civilian-targeting, particularly Coptic Christian groups and firing missiles towards Eilat to stoke tensions with Israel. The oscillating nature of the conflict serves to bolster President el-Sisi’s national political agenda by de-legitimising uprisings from below and challenges to the state from wider societal groups. This effect is not limited to Muslim Brotherhood protests, which now are almost non-existent, but extend to a variety of organised groups including health industry and factory workers, Nubian ethnic groups, and sporting clubs.

Counter-insurgency against the Sinai Province group has failed to produce the desired outcome purported by el-Sisi. The Interior Ministry regularly reports on its operations, publishing militant or police fatality figures that are often difficult to corroborate. Estimates of the Sinai Province militant group size is between 1,000 – 1,500 (BBC, 12 May 2016). ACLED has recorded at least 1,467 fatalities in sweeping operations from 2015 – 4 March 2017 suggesting either the media blackout in Sinai is making researchers underestimate the size and capacity of the group, or the Interior Ministry is fabricating reports. Clearly the second of these scenarios is more likely, given Egypt’s state-controlled media machines pumping out false reports, proclivity towards obstruction of the truth and tainted human rights record.

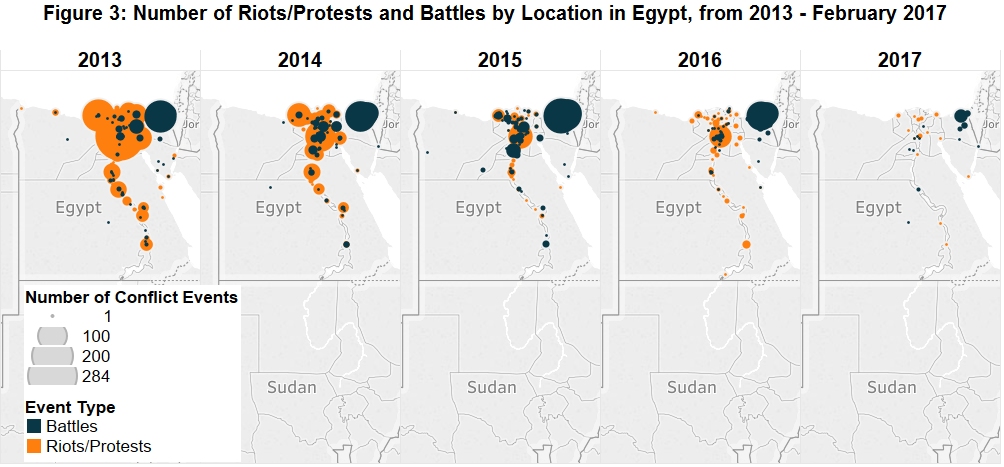

Added together, the decline in protest and sustained insurgency (see Figure 3) illustrates how el-Sisi manipulates citizen fear of instability to side-line malcontent within the broader population – a popular repertoire utilised by strongmen under authoritarian contexts (Malik, 2017). Evidence for this is only further strengthened when considering the active facilitation of social mixing in Torah Prison between known ‘extremists’ and young, non-radicalised popular demonstrators who have often been arbitrarily arrested. This strategy enables el-Sisi to paint all state-defined dissidents as potential radicals, justifying a comprehensive contraction of political space with which to express grievances or push for change. This lends more support to the theory that the Egyptian government has an interest in prolonging antagonisms in its peripheral counter-insurgency operations. This concern is only further compounded when the question of why the Egyptian regime has failed to quash this geographically isolated group is raised.

The political space left for opposition parties, civil society, and everyday citizens to express grievances has shrunk to such a low-level that current mobilisation that does occur in Egypt is contained, controlled and even ideologically supportive (even if indirectly) of the Egyptian regime’s’ interests. Take for example the One Nation Foundation’s statement in the wake of Coptic Christians fleeing North Sinai from persecution. The statement was accompanied by a number of signatories calling for a protest outside parliament against militant activity. According to Al Ahram, “organisers have said they will seek interior ministry permission for the protest, as is required under Egyptian law.” During the Red Sea island protests and following the introduction of the protest law, civil society expressed its frustration at the closing of representation and freedom of assembly. Following recent developments, the Egyptian people have seemingly, and perhaps only temporarily, decided to overlook the authoritarian tendencies of the regime elite in favour of national stability.

What does this all mean for political stability in Egypt? Afrobarometer find that citizen satisfaction with democracy in Egypt doubled in the period from 2013-2015. This perception coexists with a small reduction in some indicators of personal political freedoms, suggesting a conflation of democracy, or at least el-Sisi’s performance and policies, with stability. This supports the idea that citizens within Egypt have shifted their demands from democratisation and an opening of the political space to demands for securitisation from 2013 to 2015.

Furthermore, the findings suggest that the invisible hand of the military and intelligence services may well have had a lasting influence on the President’s strategic manoeuvring to position himself as an island of stability. He appears to have achieved this through three measures that reinforce military dominance and prowess: counter-insurgency, isolating and reprimanding the police forces, and creating an impotent parliament. First, and most importantly, through sustaining a peripheral violent Islamist insurgency, the Egyptian state can suspend its citizenry in constant fear and pursue an aggressive strategy of securitisation of the state, removing any opportunities to threaten its survival. Second, widespread police abuses across Egypt against traders, drivers, vendors, and other individuals has threatened to spark mass unrest as seen in Tunisia in 2011 and more recently in Morocco with the death of a fishmonger in October 2016. At first, el-Sisi failed to systematically investigate police abuses, arguing that these were the actions of a few individuals. As the issue became more pertinent and widespread, the perpetrators of this violence have been publicly prosecuted, making an example of the police serving to bolster the integrity of the military. Thirdly, the Egyptian parliament is, in the eyes of Egyptians, a surrogate institution to rubberstamp decisions tightly and secretively controlled and executed by a backroom elite (The Arabist, 7 February 2017). Lacking a traditional support base founded upon a political party structure, power is diffuse within institutionalised channels leading to a fractured formal political landscape dominated by individual candidates and not cohesive blocs (Al Jazeera, 12 January 2016).

As a result, the opportunity for routinized street demonstrations against the state’s political mismanagement has been reduced, as evidenced by the absence of public outcry to a suggested extension to the Presidency term limits from four to six years in late February (Egypt Independent, 27 February 2017). Whilst this litmus test has demonstrated that Egyptians are not currently as constitutionally-minded in their activism, protests over immediate economic conditions remain (Egypt Independent, 8 March 2017). Therefore, the possibility for riots and protests over a deteriorating standard of living may characterise patterns of protest in the coming months as state-society relations move away from the right to representation to the right to economic security. Should these protests remain ad hoc, sporadic, and non-organised, then the regime is likely to avoid responding with repression and protest will remain contained, following a geographical logic of economic grievance. If protests begin to demonstrate links to organised groups and start to diffuse nationally, then patterns of protest will be characterised by state violence.